The idea of writing a biography about one of the world’s best-known writers felt daunting to Melissa Sweet. What could she add to the life of E.B. White that hadn’t already been said?

But for all the books that have been written about White and all the writing he did himself, about his childhood in New York and his life on a farm in Maine, there remained a few unanswered questions that nagged at Sweet, an award-winning children’s book illustrator.

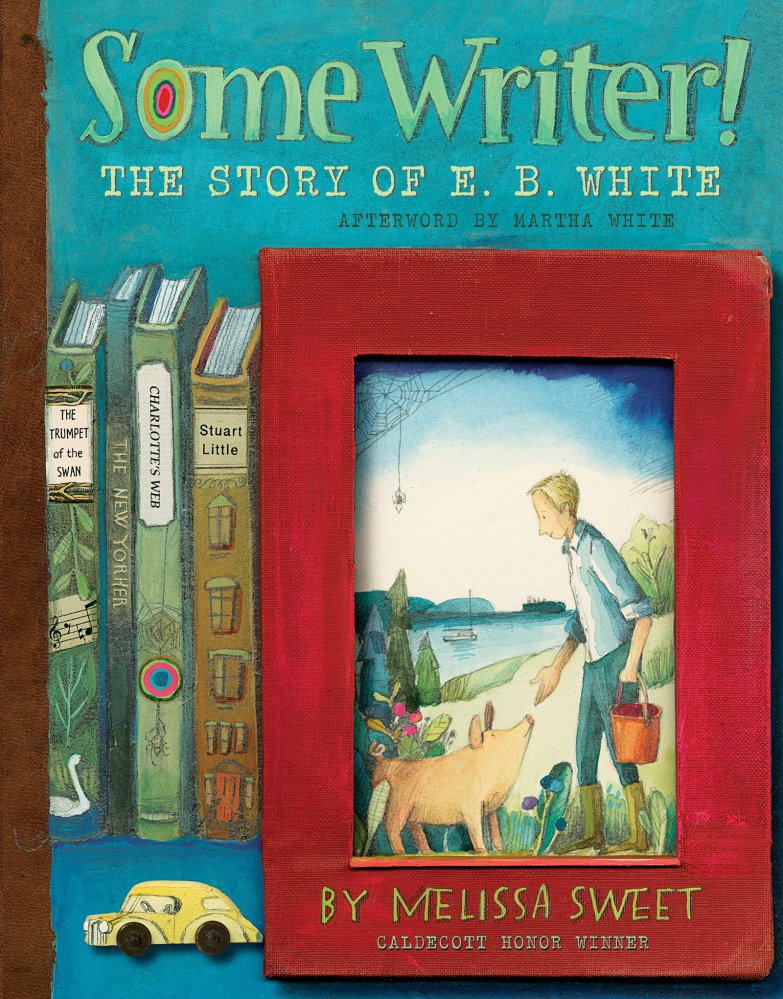

Her search for answers unfolds in her newest book, “Some Writer! The Story of E.B. White.” Sweet wrote and illustrated this book after three years of research. Using paintings, mixed-media collages and facsimiles of private heirlooms from the White family collection, Sweet has created a magical farm in the quiet countryside of Maine, where all living things are treated well and where love, happiness and hardship are part of the reward of a life well lived.

On that farm reimagined, she found the answers to questions that had piqued her interest, most pressing of all, why did American’s foremost man of letters, who filled the pages of the New Yorker with essays, commentaries, news and witty asides, also take the time to write children’s books? In his long and widely celebrated career, White wrote three of the most popular books in children’s literature, “Stuart Little,” “Charlotte’s Web” and “The Trumpet of the Swan.” All are stories about animals who rely on friendship and companionship to find their place in the world.

Sweet also wanted to know where those books came from, and she wanted to know what E.B. White was like as a little boy, growing up in what he described as “a large house in a leafy suburb, where there were backyards and stables and grape arbors.” And she wanted to know how coming to Maine and settling on a sprawling farm in Brooklin, where White and his family lived in a big white house with a big white barn and a little boathouse down along Allen Cove, changed the man and lit his imagination.

Sweet has illustrated dozens of children’s books and has specialized in illustrated biographies of famous writers for kids. “Some Writer!” – the title comes from a quote in “Charlotte’s Web” – is the latest in her series that also includes books about William Carlos Williams and Peter Mark Roget. “Some Writer!” is Sweet’s most ambitious book and, at well over 100 pages, it is arranged as a chapter book. It’s intended for kids, but Sweet wrote it and illustrated it with older readers in mind, with more text than her other books. She hopes it appeals to kids who are reading “Charlotte’s Web” for the first time – fourth-graders and older kids – and she knows, based on responses from her writer friends, that the book will find an audience with adults, as well.

Sweet’s illustrations include paintings, mixed-media collages and facsimiles of private heirlooms from the White family collection.

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt released the biography last week. Sweet begins her national publicity campaign for the book with a tour to Maine island schools. Island Readers & Writers, a nonprofit organization that promotes reading among Maine children who live in remote places, is providing copies of the book to kids on North Haven, Vinalhaven, Deer Isle-Stonington, Mt. Desert, Swan’s Island and Great Cranberry Island, and Sweet is traveling to the island schools to lead workshops.

Sweet, who recently moved to Portland from Rockland, went right to the source to tell this story. She spent many long days at White’s alma mater, Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, which holds most of his papers. She visited the White farm, which is not open to the public, per White’s wishes, and she was given access to the writer’s early journals and other family memorabilia that either hasn’t been shared with other biographers or has been overlooked.

Most important, perhaps, she spent long hours with White’s granddaughter, Martha White, who lives in Rockport and knows Sweet as a former neighbor and fellow dog walker.

Sweet tells a story about a boy who became one of America’s most beloved writers, who learned to read by sounding out words in the New York Times but who never loved books. He liked to ride bikes and climb trees. And he liked dogs. His early affection for his dog Mac cemented his lifelong respect for animals and all critters, a theme that ties his children’s books together.

She tells the story of a man ahead of his time, as well. White was a contributing writer and editor to the New Yorker for more than 50 years, and in 1959 he revised a book written by his college professor William Strunk. “The Elements of Style” became an indispensable style guide for writers, including Sweet, who said it was “Elements of Style” and not one of White’s children’s book that made her a fan. White received a Pulitzer Prize special citation in 1978.

In many ways, White was an original back-to-the-lander, coming to Maine from the city to live a simple lifestyle and raise a family and farm animals. He was also the original telecommuter. He filed his columns for Harper’s and the New Yorker from Brooklin, traveling occasionally to the city for business but choosing to do his work from the comforts of home.

One of the illustrations for “Some Writer!” is a drawing of manual typewriter. E.B. White wrote on the typewriter, and Sweet wanted to explain to readers – young readers especially, who only know how to write on a computer – what a typewriter is and how it works.

In searching through family journals, Sweet learned that White’s lifelong unease with public attention stemmed, in part, from a grade-school assembly, where White was called on to read a Longfellow poem with the words, “Footprints on the sands of time.” But he flubbed the line, and the other kids laughed.

Mac met him when he came home from school and helped ease the boy’s anxieties with his loyalty. “A boy doesn’t forget that sort of association,” White later wrote of his beloved first dog.

As Sweet began to see White as a little boy, she was able to treat her subject as a human being and not as a titan of American letters. “Once I learned all those things, I found him so much more accessible and less intimidating,” she said. “It’s daunting to take on the task of writing about a writer who is so universally loved and revered.”

THE FAMILY TROVE

Sweet was well into her research when she approached Martha White about the book. She needed permission to use some of the material and asked White, who is her grandfather’s literary executor.

White was familiar with Sweet and her work. She read Sweet’s books to her own children and grandchildren, and she appreciated Sweet’s previous illustrated biography about Peter Mark Roget, who conceived and wrote the world’s first thesaurus. “The Right Word: Roget and His Thesaurus” told the story of a little boy who loved lists and who grew into a man who created a writing tool that helped generations of writers to express themselves with clarity. The book, written by Jen Bryant, won a Caldecott Honor, a top award in children’s literature.

“My grandfather was a great thesaurus lover himself,” Martha White said. “I thought, ‘What a perfect lead-in, to do a book about words.”

After the two met, White opened up the family trove to Sweet, who had access to the most personal of E.B. White’s papers the family deemed either too private, too important or simply not appropriate for public consumption. White was impressed with Sweet’s depth of knowledge of her grandfather, and felt comfortable sharing the archival material. “She had read every book, and she was quoting E.B. White to me, which was very interesting. She may be the one person in the world who knows more about my grandfather than I do,” Martha White said. “I was 100 percent on board, right from the get-go. I knew Melissa well enough to know that, when she does a project, she does it with her whole body and soul.”

Martha White shared private family photographs, early journals that were never given to Cornell and will never be published, odds and ends, and childhood scrapbooks.

She tells the story of a man ahead of his time, as well. White was a contributing writer and editor to the New Yorker for more than 50 years, and in 1959 he revised a book written by his college professor William Strunk. “The Elements of Style” became an indispensable style guide for writers, including Sweet, who said it was “Elements of Style” and not one of White’s children’s book that made her a fan. White received a Pulitzer Prize special citation in 1978.

In many ways, White was an original back-to-the-lander, coming to Maine from the city to live a simple lifestyle and raise a family and farm animals. He was also the original telecommuter. He filed his columns for Harper’s and the New Yorker from Brooklin, traveling occasionally to the city for business but choosing to do his work from the comforts of home.

Sweet’s editor at Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Ann Rider, said White’s offer to open the family treasures to Sweet was like “being given the keys to the kingdom by the White estate.”

Instead of a picture book for children, “Some Writer!” became a chapter book for older readers and adults, Rider said. “We really believe this book will reach kids who are already familiar with his work, who have read ‘Charlotte’s Web’ and ‘Stuart Little’ and want to know more about who wrote those books,” Rider said. “But this is one of those books that can speak to you at different ages and at different times in your life.”

Sweet used the White family material to draw a more complete picture of E.B. White as a boy, his maturity into a man and his growth as a writer, husband and father. Some of the things she reproduced, others she used as inspiration for her own paintings and collages.

One of the pieces she includes in the book is a printed, bound brochure that White made at age 15 to entice a friend from New York to spend the summer with him at Belgrade Lake in Maine, where the White family came each summer. As a boy, White loved the lake, and his brochure touted Maine as “one of the most beautiful states in the Union.”

Sweet unearthed a few revelations that will be of interest to White scholars, Martha White said. No one before has reported that White was reading Longfellow when he stumbled on the words, leading to a lifelong aversion to attention. Or that his older brother Stanley was called “Bun” because he could wiggle his nose like a bunny.

She most appreciates Sweet’s illustrations of her grandfather and his “vile” dachshund, Fred. Martha White described the dog pictures as “spot-on,” and said the portraits of her grandfather “are more like my grandfather than many photos of him.”

Sweet lived with the material in her Rockport studio for long stretches, getting to know White not only through his words but through his possessions. In time, she felt his presence in the studio, both haunting and humbling. For a while, she kept White’s personal copy of “American Boy’s Handy Book,” a Bible of boyhood for large numbers of American kids. White used the book to build his son Joel a scow, “using pluck in place of know-how.” Sweet includes a copy of the book’s pages in “Some Writer!”

Living with such a personal possession, Sweet said, felt monumental. “It actually made me speechless, to have that object in my studio. It was like having the Hope Diamond,” she said.

AT HOME IN BROOKLIN

Sweet especially enjoyed her trips to Brooklin. White was very much a New Yorker, but when it came time to commit to a lifestyle, he chose the farm in Maine, where he raised animals and lived among 40 acres of solitude. He and his wife, Katharine Angell, bought the farm in Brooklin in 1933 and by 1937 were living there full-time.

White kept a monthly column in Harper’s and wrote for the New Yorker, filing dispatches from Maine on a Corona manual typewriter.

Maine charmed White, and he fell easily into the rhythm of caring for animals and being at peace with nature. Although he began “Stuart Little” while living in New York, White didn’t finish it until coming to Maine and settling into life on a farm. White wrote of coming to Maine what many people feel still today: “What happens to me when I cross … into Maine …? I cannot describe it …. but I do have the sensation of having received a gift from a true love.”

The farm in Brooklin is still very much as it was when White lived there. He died in 1985 and made it clearly known that he did not want the White farm to become the subject of any sort of memorial or destination for tourists. He valued his privacy in life and insisted on it in death.

Sweet went to the farm to get a sense of its perspective. She befriended the current owners, Robert and Mary Gallant, whom she thanks in the book. She walked the grounds and spent a lot of time in the barn that became famous in “Charlotte’s Web.” She leaves most of the details of the place itself out of the book, out of respect for White.

“He did not think authors should be celebrities,” White’s granddaughter said. “He never wanted his private home to become a museum or a pilgrimage in any way. People tried to do it, and still do today. But he was absolutely clear that it was something he did not want.”

Sweet wasn’t interested in documenting White’s celebrity or his place in the world of literature. Those books, she said, have been written.

She was interested in finding the child within the man. Near the end of her book, she includes a quote from White, written when he was 84, a year before he died. He was blind in one eye and suffering other losses. But he felt well enough to tool around on his three-speed Raleigh. On his ride, a coyote emerged from the woods and followed him down the road, delighting him and stirring his imagination.

“I don’t think he was anything but curious, but it was kind of spooky to have a wild animal trailing me,” White wrote. “I was probably his first octogenarian on wheels, and he just wanted to get a good look at it.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.