Alex Koch swung the Emerson Stevens Victory ax, made around 1934, over his shoulder and down into a birch log with a craaack, splitting it into pieces just big enough for a wood stove.

This is the sound of autumn in Maine. Homeowners are splitting and storing firewood for coming winters, often using an ax that seems to have been in the tool shed forever.

Koch, 32, is an ax collector from Unity who delights in using restored vintage axes. Koch and other ax experts in Maine say they’ve seen a renewed interest in vintage axes over the past five years, especially among young people who are trying out homesteading or farming or otherwise working with their hands.

“People are tired of the throw-away culture,” Koch said. “They want things that will last, and vintage axes will do so.”

This year, for the first time, the Common Ground Country Fair hosted an Ax and Saw Meet-up, where ax junkies could gather and swap stories. Koch, who refurbishes old axes, is getting emails from as far away as Europe and Australia from collectors asking about vintage Maine axes. Ax fans have Facebook pages, including a group called “Axe Junkies” with nearly 18,000 members.

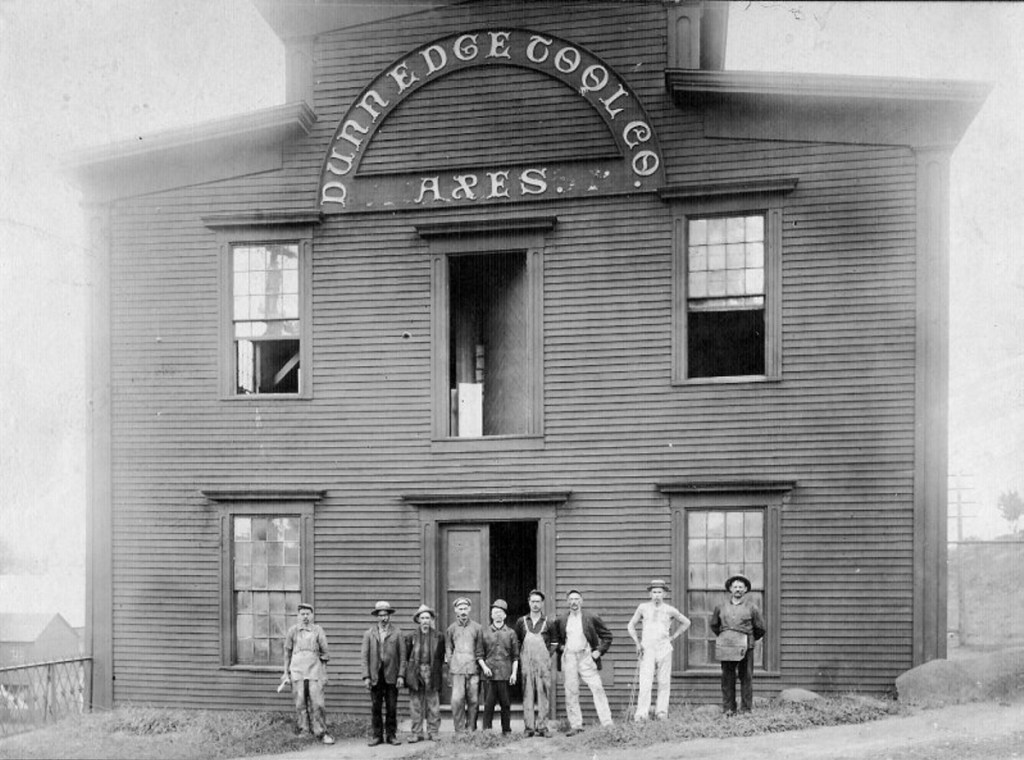

It’s especially satisfying to see this resurgence here, as in the 1800s and early 1900s, Maine had a thriving ax manufacturing industry. It was tied, not surprisingly, to its thriving lumber industry. The town of Oakland, especially, was the “scythe and ax manufacturing capital of the world,” Koch said.

He estimates that over a 100-year period 18 ax manufacturers plied their trade in Oakland, or West Waterville as the town was previously known, including such well-known makers as Spiller and Dunn Edge Tool. They made ax patterns with names that today sound almost romantic: the Maine wedge, the Rockaway, the Ship’s Carpenter, the Georgia Long Bit, the Lumberman’s Pride and the Cock of the Woods.

Smaller manufacturers were located in towns scattered around the state, including but by no means limited to Skowhegan, Belfast, Bath, Westbrook, Greenbush and Kingfield.

Koch and other ax fans estimate Maine had as many as 300 ax makers between 1800 and 1960, both larger manufacturers and simple blacksmiths. Ax makers supplied the state’s many lumberjacks and its many shipbuilders.

“There were people everywhere making axes,” he said.

Many of them can be found in “Ax Makers of Maine,” a self-published list of ax manufacturers that was started by a Mainer, the late Donald G. Yeaton, and is now regularly updated by Art Gaffar, a tool expert who lives in South Portland. Koch treasures his reference copy, along with a large collection of beautiful vintage ax labels he has preserved in a big binder.

In the next 18 months or so, the list may get an additional name.

BRINGING BACK MAINE-MADE

Five years ago, Scarborough school psychologist Steve Ferguson went shopping for an ax to give to his godson, who was going to forestry school. He wanted to get the young man a classic ax from Snow & Nealley, which had been making axes in Maine since 1864. But Snow & Nealley’s production, he soon discovered, had been outsourced to China. His reaction was immediate and strong: “How can there not be an ax company in the state of Maine?”

(An Amish family in Maine has since purchased the company, according to the online blog Lehman’s Country Life, and Snow & Nealley axes are now made in the United States again.)

But Ferguson had spotted an opportunity. Eighteen months ago, he formed a partnership with his brother, Mark, a Portland attorney and software company owner; and Barry Worthing, a nurse at Maine Medical Center. The three launched Brant & Cochran, a company aimed at bringing handmade axes back to Maine.

They might seem an unlikely trio for the task. None of the three is a longtime ax expert. Rather it was their love of history that drew them to axes, and they are figuring it out as they go. To learn about the industry’s history and the market for craft-made axes, they visited craft fairs, outdoorsman shows, historical societies and the New York State Woodsmen’s Field Days. They tapped local forgers as mentors.

Now, in his spare time, Steve Ferguson can be found at the company’s workshop at Thompson’s Point in Portland, refurbishing family heirloom axes for people from all over the country.

“Some of these take you 20 minutes. Some take you two hours,” he said on a recent weekday afternoon as he used a spokeshave to shape and smooth an ax handle made of Tennessee hickory.

So far, Brant & Cochran – named after the tool supply business the Fergusons’ grandfather once owned in Detroit – focuses on restoring vintage axes. But this winter, the partners hope to team up with local blacksmiths and begin forging new ax heads. At the same time, they are searching for a partner who can mill Maine ash for the handles.

Mark Ferguson estimates the company is a year to 18 months away from having a brand new, Maine-forged ax ready to market. Their first ax will be the Maine wedge, which hasn’t been made here since ax maker Emerson Stevens went out of business some 50 years ago.

MUSEUM PIECES

If you’re interested in old axes, the place to go is the Patten Lumbermen’s Museum, which has a vintage collection of about 50 axes, some of which date back to the 1800s. The axes were donated by Mainers and were made in Maine and Canada. In recent years, Executive Director Rhonda Brophy has noticed visitors taking more of an interest in the collection.

“They’re just amazed at how things were manufactured that many years ago and how they were able to making a living with an ax,” she said. “What would it be like to work in the woods all day? The amount of calories they had to consume was probably huge.”

Back in the day, fathers taught their children how to use axes to prepare them for working in the woods as adults, she said.

When Brophy met the Brant & Cochran partners, she told them about a stash of 30 to 40 old ax handles in the attic that had been donated to the museum. The company bought 20 of them to use in their restoration work, including some rare – though not especially useful – Adirondack handles with a double bit and curved handle.

“No one knows why they decided to make these (curved) handles,” Steve Ferguson said. “One side has really good ergonomics, and the other side is kind of goofy and backwards.”

AX APOSTLES

Though they were business competitors, the ax companies that once flourished in Oakland often worked together, according to Koch. “Companies would jointly order shipments of steel to get a better cost,” he said, “and occasionally would share employees,”

In the end, though, cooperation couldn’t save them. Ax manufacturing in Maine went into decline, victims of the Depression, World War II – when the best steel went to the war effort – the suburbanization of America, foreign imports and the advent of motorized chain saws.

Though early chain saws were huge and some required two operators, they were “still easier than wielding the ax all day,” Brophy explained.

But if the heyday of ax making in Maine is long gone, vintage axes from that time are back in demand – not just for collections, but for daily use. People appreciate how well they were made.

“The quality of Chinese- and Mexican-made axes that you get is quite frankly rather terrible,” Koch said. “There’s just no way to compare those to the quality of a vintage ax from Oakland or anywhere else in the United States.”

Vintage axes, on the other hand, “should last forever if they’re taken care of,” Mark Ferguson said. His company charges $75 to $95 for ax restoration. So far, customers range from outdoors people, camp owners and young people in the forestry industry to those who find their great-great grandfather’s ax in the attic and want to preserve it so it can be handed down to a new generation.

The partners in Brant & Cochran have become ax evangelists. They hope their small efforts to educate people will help jump start the industry. Because Maine without an ax industry just isn’t right, Mark Ferguson says.

Send questions/comments to the editors.