BRUNSWICK — It’s all about the soybeans.

To make the best tofu, says Saskia Poulos, kitchen manager at Tao Yuan restaurant, start with the best quality soybeans. Tofu is, after all, just soybeans and water.

She pinched open a plump dried bean that had been soaked overnight, revealing a light cream-colored interior.

“You just want to make sure that they’re super hydrated so they’re nice and creamy all the way through,” Poulos said.

Once a week, sometimes twice, Poulos comes into the kitchen at Tao Yuan before the cooks arrive for the day to make the soy milk that will then be used to make a batch of tofu. Tao Yuan has not done a lot with tofu in the past, but after chef/owner Cara Stadler returned from a trip to China in January, she realized “we need to be using more of it.” (Stadler’s maternal grandparents are Chinese.)

Stadler acknowledges there are local companies making perfectly fine tofu, and purchasing it could save her staff time.

“But everything is better when you do it yourself,” she said. “You have control of the product. You have the consistency you want. You have the texture.”

It’s part of a broader philosophy that has Stadler slowly working her way through the Tao Yuan pantry, finding ways to make her own versions of products the restaurant had been buying commercially. Making tofu brings Stadler close to another key goal, as well – preventing waste in her kitchen.

“We started making our own miso a few years ago,” she said. “We’re trying to figure out how to make all of our brown sauces on our own. I’m trying to make my own black bean chili sauce. We’re in the process of trying to make almost everything in-house if we can. And tofu is easy to make.”

Poulos may now be the designated tofu maker, but until just a few weeks ago she was a complete novice. Her first step was sourcing. So many soybeans are genetically modified, but Poulos was determined to find a company that grows non-GMO soybeans. She found it in Laura’s Soybeans, grown on a large family farm in Iowa.

Next, she consulted Andrea Nguyen’s book, “Asian Tofu: Discover the Best, Make Your Own, and Cook It at Home,” and watched Nguyen’s YouTube video four times before she felt ready to try making tofu herself.

It’s a simple process, she said, but it can be tricky if you are – as she is – experimenting with different textures.

To make a small batch – one large block of tofu – Poulos starts by making soy milk: she soaks 170 grams of dried soybeans in 2 quarts of water overnight. After draining the soybeans, Poulos blends them with some of the soaking water until the mix is the consistency of a milkshake.

As she works, she occasionally refers to handwritten notes she’s made during previous tofu-making sessions. Other than the restaurant’s pastry chef, she is the only one in the small kitchen at mid-morning – the cooks won’t arrive until nearly noon.

A coagulant separates the soy milk into curds and whey, which Saskia Poulos ladles into a lined bamboo tofu mold. Staff photo by Jill Brady

Poulos gently pours the contents of the blender into a pot of hot water on the stove top; a giant pot of chicken-and-duck stock has been simmering all night on an adjacent burner. She stirs the soybean mixture frequently as it heats up to prevent it from sticking. As soon as it starts to foam and rise – like dairy milk, it will boil over if not watched carefully – Poulos turns off the heat and strains the soy milk through a cloth-lined sieve.

Soy milk is typically strained through a double layer of cheesecloth, but Poulos has found something better – the cloth bags used to pack scallops at Upstream Trucking, the restaurant’s seafood purveyor. (They are washable and reusable.)

Poulos squeezes and presses the solids left in the bag to get as much milk out of them as she can; she pours a little more reserved bean soaking water over the solids to extract the maximum amount of milk.

CREATIVE USES OF BYPRODUCTS

The soybean solids, or soy pulp, are known as okara in Japanese, and they never go to waste in Stadler’s kitchen. She’s found a variety of uses for them. The texture resembles an almost gritty paste, but the taste, like tofu, is a blank slate, “so it’s super versatile,” Poulos said.

For one, Stadler uses the okara to fill a dumpling, first sauteeing the pulp with abalone mushrooms, ginger, garlic and soy, and serving the dumpling with broth made from kombu seaweed and scallop “feet.” (Scallop feet are muscles too tough to serve, so Stadler dries them, then rehydrates and shreds them to use in soups or sauces.)

“It almost tastes like creamy shellfish because these mushrooms, when they cook, taste like shrimp, and this (okara) acts like ricotta,” Stadler said. “We ended up pairing it with a shellfish broth because it tastes so seafoody. But it’s just a really interesting flavor and texture.”

Stadler also uses the okara in yangyou ma doufu, a creamy spread she describes as “Chinese-style hummus” because it has similar consistency and is served with flatbread. That dish, which also calls for fermented greens, lamb belly, lamb fat and chili oil, is “a byproduct dish,” she said, not only using up the okara but also other leftover ingredients from making other dishes. “It’s making sure we don’t waste anything,” Stadler said, “and it’s one of my favorite dishes.”

As for the soy milk, Tao Yuan uses some of it for an egg custard topped with steamed fish, but the bulk of it goes to make tofu.

PROTECT THE TEXTURE

To make the tofu, Poulos heats the soy milk to a simmer. As it’s heating, she points out a thin skin that develops on top. Tofu skin is used in many Asian dishes, usually commercial skins that have been dried. “You rehydrate them, and they’re really delicious,” Poulos said. (Finding ways to use the skin is the next project at Tao Yuan, but the restaurant doesn’t yet make enough tofu to keep the skin on the menu consistently, Stadler said.)

Once the soy milk is simmering, Poulos turns down the heat to “let it do its thing for 5 minutes.” Meanwhile, she adds nigari, a coagulant, to water, stirring until it dissolves. She takes the soy milk off the heat and stirs it vigorously while she pours in some of the coagulant. She stops stirring, but holds the spoon in the middle of the pot to help slow down the movement of the soy milk.

The tofu is starting to set up. Poulos adds more coagulant, a little at a time, dripping it around the pan for full, even coverage. She puts a lid on the pot and sets a timer. Three minutes later, she adds the last of the coagulant, agitating it to disperse it.

“You see how it’s separating out so you have essentially curds and whey?” Poulos asked.

Poulos assembles her wooden tofu mold – she bought it on Amazon – and places it in a perforated pan. She lines the mold with a scallop bag, wets the cloth with some of the whey and starts ladling in the curds and whey. The whey drips through holes in the side of the mold and a slit in the bottom, then through the perforated pan.

“This is important,” Poulos instructed. “You want to get it in the biggest clumps, the biggest pieces, that you can, because that also affects texture.”

Owner/head chef Cara Cara Stadler garnishes mapo doufu, made with from-scratch tofu, at Tao Yuan. Staff photo by Jill Brady

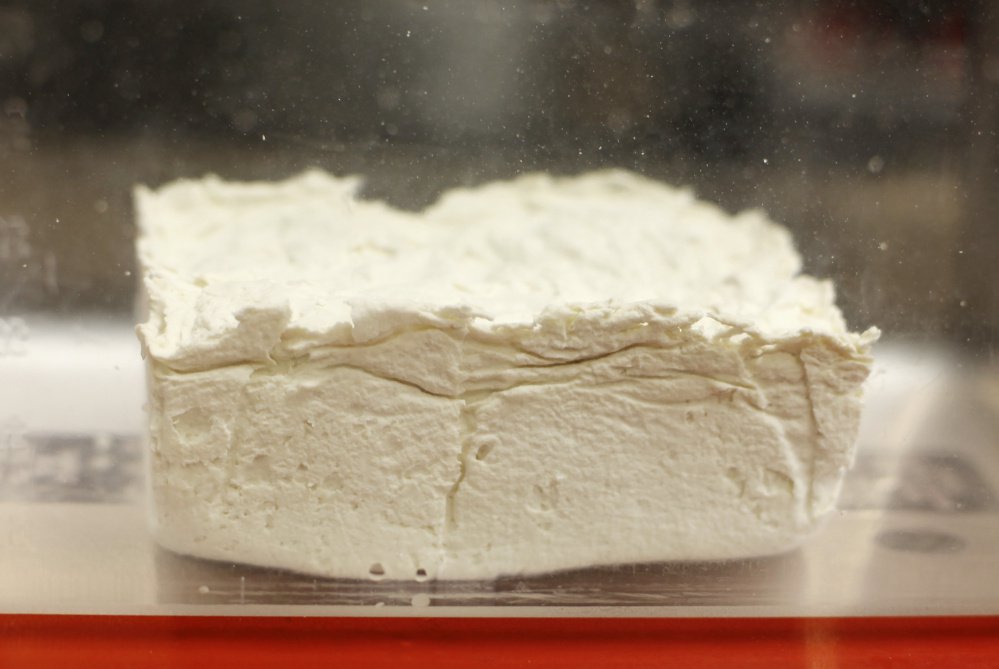

When it’s done draining, she folds over the cloth and then weights it down. Now Poulos lets the curds set up for 15 to 20 minutes. What she removes from the mold is now tofu, which is stored in cold water in a plastic tub. The whole process has taken no more than an hour and a half.

The leftover whey – it’s known as tofu milk – gives Stadler yet another opportunity to recycle: it can be used in rice dishes or to braise meats.

‘SUCKS UP SAUCE’

Tao Yuan’s tofu tastes incredibly fresh, as if it had been made with spring water instead of ordinary tap water. The texture seems smoother than store-bought tofu.

It absorbs flavors better than commercial tofu, Stadler says.

“Anything fresher is better,” she said.

Stadler uses the tofu in dishes such as mapo doufu, a popular dish that will be featured at her Sichuan regional dinner March 19. She has been freezing the tofu, too, because “it creates this weird structure. Then when it defrosts, it’s like a sponge. It sucks up sauce.” And she’s working on ultra-dense, “super-pressed” tofu to use in salad.

“It’s not easy to do because we can’t get the pressure right,” Stadler said. But made commercially, she said, it “tastes disgusting, so until I learn how to make it myself I’m never going to have it on my menu.”

Smiling like a kid anticipating her first time at bat, Stadler said she also wants to make “stinky tofu,” or choudoufu. This fermented tofu smells, she says, like “straight-up dirty gym socks.”

But it tastes great, she adds.

“If I can find a way of doing it, I’m doing it,” she said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.