In December, the Episcopal Diocese of Los Angeles declared itself a “sanctuary diocese.”

The resolution adopted by the California diocese states it will resist efforts to deport millions of undocumented people or eliminate the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program. For some churches, it could also mean offering living space to people who are at risk of deportation.

On the other side of the country, the Maine Episcopal Diocese took note.

“We’ve had a few inquiries from priests at individual churches,” said Heidi Shott, the diocese canon missioner for communication and advocacy. “They’ve come to the bishop and said, ‘Can we do this? What if?’ ”

The Pew Research Center estimates Maine has one of the smallest populations of unauthorized immigrants in the country – fewer than 5,000. So far, attorneys say there is no evidence deportation efforts have ramped up in the state.

A sign offers a proverb as a welcome to visitors at the entrance to the sanctuary at First Congregational Church. Several churches in Greater Portland are discussing how to shelter undocumented immigrants at risk of deportation. Staff photo by Ben McCanna

But the local Episcopal diocese has scheduled a video conference with its counterpart in Los Angeles to learn more about sheltering undocumented immigrants. A small number of local churches in other denominations are also researching the idea, though some said it was too early to discuss publicly.

“It is a complicated and difficult set of circumstances to wade into,” said the Rev. Jane Field, executive director of the Maine Council of Churches. “Every congregation could come out in a different place as to how they want to respond. But to do nothing or to not even talk about it is unthinkable given our current set of circumstances in the state and the nation and the world.”

Field said she is not surprised the idea has taken hold nationally and in Maine.

“We have to be asking ourselves in part because our scripture that we hold sacred says welcome the stranger,” she said. “The Old and New Testaments are pretty clear about that. The fact that churches are wrestling with how to respond is entirely appropriate.”

The practice of seeking sanctuary in a place of worship can be traced back centuries. Fugitives could find safe haven in Christian churches even during the Roman Empire. In medieval times, people accused of crimes could find temporary refuge in churches in England.

In the United States, the modern sanctuary movement has roots in a 1980s effort to shelter Central American refugees fleeing civil war. The idea spread when deportations increased under the Obama administration, but grassroots coordinator Church World Service estimates the number of churches willing to harbor undocumented people has doubled to 800 since President Trump’s election.

It is unclear how many churches across the country are offering sanctuary and how many are actively sheltering immigrants. But the movement has interest nationwide. A church in Denver attracted national news coverage in February when it took in a woman fleeing deportation. The Boston Globe reported at least three Boston-area congregations are willing to house undocumented people.

Participating in such a movement raises significant questions for local congregations.

‘LIVING OUT FAITH NOT ALWAYS SAFE’

“What does it really mean?” Shott said. “What are the implications for our churches? Would it be breaking the law in some way, and would people in our churches be willing to do that if that’s the case? We don’t have answers at this point, but in this climate, it’s worth asking those questions.”

An officer with a warrant can arrest an undocumented immigrant in a place of worship. But a 2011 memo states that U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials should avoid detaining people in “sensitive locations” like schools, hospitals or churches. That policy is still in effect but could be revoked. A public affairs officer for ICE did not respond to an email inquiry about changes under the new administration.

Harboring undocumented immigrants is a crime, and The New York Times reported in 1986 on the convictions of several clergy members involved in smuggling Salvadorans and Guatemalans into the United States. Sue Roche, executive director of the Immigrant Legal Advocacy Project in Maine, said the legal ramifications of offering sanctuary are unclear, and she encouraged any immigrant fearful of deportation to speak with an attorney about his or her rights.

None of the churches contacted by the Maine Sunday Telegram said they knew someone in immediate danger of deportation. Most began looking into the idea because of interest from ministers or members.

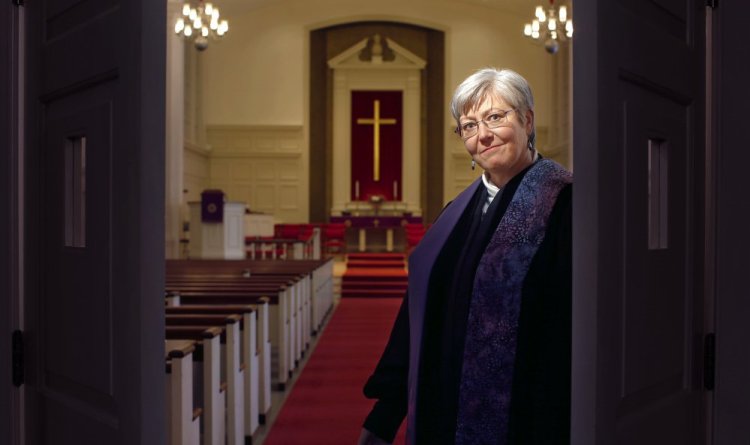

The Rev. Cindy Maddox said First Congregational Church in South Portland is also in “the information-gathering stage.”

“The legal ramifications and the safety issues are certainly some of our concerns,” she said. “But we also are aware that living out our faith is not always safe.”

Prompted by emails from her congregation, Maddox said she is seeking more information. Her broader denomination, the United Church of Christ, is hosting a webinar about offering physical sanctuary to undocumented people. While the idea has not yet been presented to the congregation as a whole, Maddox said the membership of First Congregational Church would make a final decision together.

Shott said churches from different parts of the state have expressed interest, including southern Maine and Down East.

“We can’t mandate every congregation must be a sanctuary congregation,” she said.

Allen Ewing-Merrill, lead pastor at HopeGateWay in Portland, said he isn’t aware of any tangible plans to offer sanctuary to undocumented immigrants. He and other local clergy are talking about how to help in other ways – for example, by issuing a public statement of support.

“Clergy leaders and faith communities want to be sure that anything we do or say doesn’t further jeopardize immigrant communities,” he said. “We want to make sure that anything we do or say has integrity, and we are in conversation with the people who are most likely to be affected by it.”

Megan Doyle can be contacted at 791-6327 or at:

mdoyle@pressherald.com

Twitter: megan_e_doyle

Send questions/comments to the editors.