WILTON — Tim Lovett admits he’s a perfectionist. It was the opportunity to work in thousandth-of-an-inch increments, after all, that drew him from carpentry to furniture making.

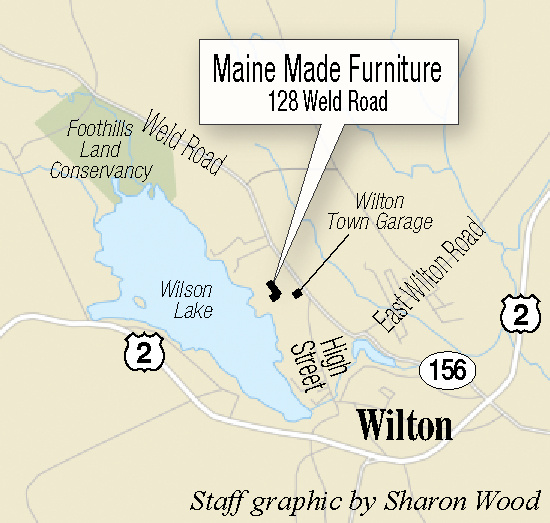

Lovett is the new owner of Maine Made Furniture, a custom furniture shop that relocated to Wilton’s former Bass Shoe Factory industrial park in September. As he settles in Wilton, Lovett has laid out plans to grow his customer base, his footprint in the one-acre factory space his company now inhabits and the number of employees on his shop floors, all welcome news for a region plagued by shuttered mills and manufacturers.

But Lovett said his success was by no means assured. He credits a community of development organizations, advisers, contractors, electricians, town officials and business partners with helping him make his dream of a custom furniture shop possible. As he looks forward to his company’s future, Lovett said he is determined to give back.

It was only a year ago that Lovett, 39, sat contemplating his impending 40th birthday, wondering what he would have to show for himself by then. He knew he wanted to be “a maker,” the guy at the bench who crafted raw materials into unique pieces of long lasting furniture, but he hadn’t quite gotten there.

In 2010, Lovett enrolled in a 12-week furniture intensive program at the Center for Furniture Craftsmanship in Rockport, where he spent more than 100 hours a week working in the school’s 24-hour workshop. At the school, Lovett connected with a classmate, the only other person who showed up as early as he did and stayed well beyond their other colleagues.

After months working alongside each other, Lovett’s classmate made him an offer: He would buy a building for a shop in the greater Portland area if Lovett bought the equipment to furnish it.

“We made a spit and a handshake deal,” Lovett remembered.

LABOR-INTENSIVE

But Lovett had to figure out how to make the enterprise profitable. Expensive furniture didn’t roll out the door every day, he knew, but the bills would certainly keep rolling in. He started looking for something that could be built through a simple production line, pieces that could be fitted together that also wouldn’t require extensive storage. He toyed with the idea of beehives, but found he couldn’t compete with outfits in the Midwest.

Then he got a break. In furniture school he landed a job as a hand-tool demonstrator for Lie-Nielsen Toolworks, a manufacturer of high quality hand tools. The company flew him around the country for weekend hand-tool events. When they learned Lovett was setting up his own shop, they commissioned 200 heavy butcher-block table tops, 6- to 8-foot wooden table tops weighing 240 pounds each.

Lovett couldn’t believe his luck and said he and his business partner worked 60- to 80-hour weeks to fulfill the order.

“It was very labor intensive because we didn’t have production floor machinery, so we were doing it largely with hand tools,” Lovett said. “It really beat you up over time.”

But the two men were building momentum. Lovett found a consultant to help with their business model. With the consultant’s help, Lovett was able to identify 95 percent of the costs to produce the table tops, allowing him to set a price point that would keep the business profitable.

Within six months the men had paid off a $45,000 loan they had taken out to set up the business. They brought in enough money to pay themselves every week that year — not much but it was still an income — and the company made $40,000 beyond that.

Despite their success, however, the workload had put a strain on Lovett’s friendship with his business partner and the two eventually parted ways, sending Lovett on a new hunt for shop space. He searched from Portland to Biddeford to Auburn, thinking he’d found just the place three or four different times until something inevitably fell through.

With the table top orders piling up, Lovett reached out to Maine Made Furniture Company to see if they could help him. Within minutes of arriving at the company’s Rumford location and meeting general manager Jared Smith, Lovett realized that Smith was the production guy he had aspired to be. Up until that point Lovett had struggled with the idea of delegating work to other people, but in Smith he found a maker whose skills outmatched his own.

While visiting the shop, Lovett also learned that Maine Made was up for sale. It almost seemed too perfect. Five years earlier as he sat with his classmates at the Center for Furniture Craftsmanship discussing potential names for their future companies, Lovett had bemoaned the fact that “Maine Made Furniture” was already taken.

“That name just sells itself,” he had told them.

WILTON APPEAL

Now here he was in 2016, presented with the opportunity to own the name and work with the equipment and skilled craftsmen Maine Made employed. On Sept. 23, he closed on the company, taking out loans and drawing on his wife’s retirement account to make the deal happen. “I think we put our youngest kid up against the business,” he joked.

On Sept. 29, they moved to Wilton.

Lovett credits a long list of people for making the deal and the move happen. Western Maine Development Group, the company that owns the former shoe factory, gave him discounts on rent and helped him with his build out. Local contractors and electricians went above the call to cut their own costs, stripping wire from decommissioned mills and repurposing existing infrastructure wherever possible.

The town of Wilton issued Maine Made a loan from its small line of revolving credit. Town Manager Rhonda Irish and development consultant Darryl Sterling worked with Lovett to identify additional contacts, loan and grant opportunities.

“The list of people, it goes on and on for how people have bent over backwards to try to make this a reality,” Lovett said. “The town has been incredibly willing and accommodating.”

Wilton has also agreed to sponsor Maine Made’s application for a workforce development grant that would help cover Lovett’s payroll costs as he trains new and existing employees on equipment in his shop. Lovett hopes the grant will help him boost Maine Made’s employees from 12 people, including Lovett, to 18 by the end of the year. Ideally, Lovett said, he’ll do all his hiring locally.

BUILDING COMMUNITY

The company has already secured new contracts, including a deal with Sunday River to build 1,000 pieces of furniture for the resort’s Grand Summit Hotel. Lovett said they’re also working to develop a website that will allow customers from anywhere in the world to design custom pieces using predetermined options including leg styles, wood species and finishes.

“This is the part I get excited about because there’s so much possibility, and there’s really no build-your-own furniture sites,” said Barrett Stowell, a consultant and designer who has worked with Maine Made for several years.

Stowell, 33, was born and raised in Weld and has been working as a designer in Boston for over a decade. His previous work with Maine Made includes a men’s store for Saks Fifth Avenue in New York, where Maine Made’s craftsmen built out the custom wood racks and pieces using designs of a team of which Stowell was a member.

Stowell is currently helping Maine Made with its re-branding and design in the hopes that Maine Made will secure enough business to allow him to move back to the area. He is eager to return to the area after years of urban living.

“I’m not a city boy,” he said. “I want to move back in the worst way, and the only way it’s possible to do what I love is to create my own opportunities, which is why working with these guys is a big jump in that.”

In addition to the website, Lovett envisions building out a showroom next to his Wilton shop, where would-be customers could survey existing pieces and look back into the shop’s inner workings. With Wilton’s efforts to revitalize the town and make it more appealing for business and tourism, Lovett said he strongly believes people will make the trip.

Lovett also has his sights set on out-of-state customers and envisions sales trips to New York and Massachusetts in his future. But always present in his vision is the idea of giving back to the community that helped him get here.

“Ultimately we’d like to fill the entire 44,000 square feet with machinery and employees,” Lovett said. “There used to be 1,200 people employed on this property, and they’re storing cars on it. So we’ve got to inch our way back up in that direction.”

“It’s about building the community and maintaining a sense of community,” he continued. “The rising tide lifts all boats. That’s the approach that we subscribe to.”

Kate McCormick — 861-9218

kmccormick@centralmaine.com

Twitter: @KateRMcCormick

Send questions/comments to the editors.