Place your cursor on a photo for buttons that allow you to pause or move ahead at your own pace.

Fourth of 10 parts.

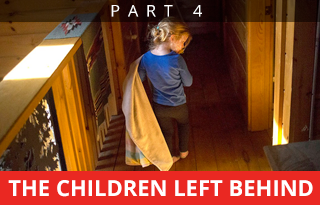

Most nights, 2-year-old Claire Smith sleeps in the bedroom that once belonged to her mother.

A hand-colored sign with her mother’s name still marks the door: “Ronni.”

In the bathroom next door, 23-year-old Ronni Baker overdosed on heroin and fentanyl two years ago. The blue urn with her ashes is downstairs in the living room of her parents, Matt and Cheryl Baker of Stow.

“It was a shock,” said Matt Baker. “You’re 49 or 50 years old, and you’re thinking about retirement, and all of a sudden you’re raising a 9-month-old.”

As heroin kills one generation, it leaves another without mothers and fathers.

In 2015, Ronni was one of a then-record 272 people who died of drug overdoses in Maine. That number was eclipsed in 2016, when the overdose death toll leaped to 376.

National and state data don’t specify whether overdose victims had children. However, more than half of the people who died in Maine in 2015 were in their childbearing and parenting years, between 18 and 44 years old. Among the more than 60 overdose victims whose loved ones agreed to share their stories with the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram, more than a third were parents.

The surge in opioid addiction is reverberating through the child welfare system, the courts and the homes of many aging Mainers.

Last year, the Department of Health and Human Services removed 411 children from Maine homes where a parent’s drug use put them at risk. That’s a 45 percent increase from 2009, and Jim Martin, the director of the Office of Child and Family Services, said the prevalence of drug use is likely underreported by caseworkers.

DHHS has made a plea for more foster families, especially for teens, youth with special needs and sibling groups of three or more.

“The opiate and heroin epidemic facing Maine and the rest of our nation is destroying the fabric of our families and communities,” DHHS Commissioner Mary Mayhew said in a July 2016 press release. “We have an obligation to support these children and provide them with a safe and stable home.”

The state places children with their own relatives whenever possible, so grandparents are often thrust back into parenting roles. Generations United, a national nonprofit based in Washington, D.C., estimates that for every child placed with a relative through the foster care system, 20 children live with relatives outside the system. Probate courts have seen an increase in emergency petitions for minor guardianship.

National experts and state officials said these trends are directly related to the heroin epidemic.

“The nature of opioids obviously means that the overdose deaths are increasing,” said Dr. Nancy Young, director of the national policy institute Children and Family Futures in California. “We have children without birth parents still living that could reunify with them.”

BUSY DAYS KEEP GRANDPARENTS’ GRIEF AT BAY

Claire has her mother’s soft mouth and her father’s fair hair. Cheryl Baker helps her granddaughter pull her pink owl hat over those blond waves and holds her hand as they navigate the icy driveway to the car on a Saturday in February.

They set out on a busy day: gymnastics class in nearby Conway, N.H., a stop at Matt’s mother’s house in Stow, lunch and naptime back at the Bakers’ house, then an overnight visit with Claire’s father.

Cheryl takes Claire to gymnastics class in Conway, N.H. Cheryl and Matt have adjusted their work schedules to make themselves available to pick Claire up from daycare and take her to activities. Staff photo by Brianna Soukup

“Can I have a Tic Tac?” Claire asks from her car seat.

Cheryl gives her two. Claire is quiet for a few minutes, but her small voice soon calls up to the front seat.

“Can I have a Tic Tac?” she asks again.

Cheryl shakes her head and smiles, but she gives Claire one more mint. These busy days keep the Bakers’ grief at bay.

“She can lift you out of the doldrums,” Cheryl says.

Cheryl, 52, works in special education in Fryeburg public schools. Matt, 50, is a longtime sergeant at the Oxford County Sheriff’s Department. Both have full-time jobs, but Matt switched his schedule to work fewer night shifts after Ronni died. Cheryl sometimes rushes to leave work in time to pick Claire up from daycare or bring her to her dad’s house for a visit. The couple joke about learning to change diapers all over again.

For some families, the transition is more difficult.

Bette Hoxie, director of Adoptive and Foster Families of Maine, said her organization often hears from grandparents who are caretakers again because of addiction in their families. Some ask questions about supervising visits with a parent, or raising a baby exposed to drugs before birth. Others struggle to make ends meet on a fixed income, or they move out of senior living to accommodate their grandchildren.

“Grandparents don’t raise their children thinking, ‘Now I’m going to get to raise my grandchildren,’ ” Hoxie said.

FROM THE EDITOR

COMING WEDNESDAY: Treatment dilemma: No consensus on cure as demand for it explodes

Hoxie testified at a March 21 hearing of the U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging in Washington, D.C., focusing on the challenges faced by those who are raising their grandchildren as a result of the opioid epidemic. The panel, chaired by Maine Sen. Susan Collins, is not considering any legislation on the subject but scheduled the hearing to raise awareness and gather information.

‘ALL OF A SUDDEN, HEROIN WAS EVERYWHERE’

In rural Stow, Ronni grew up hunting with her father and mucking horses’ stalls with her mother.

The Bakers know Ronni drank alcohol and smoked marijuana at high school parties, but they aren’t sure when she began using pills. It might have been during her short stint at Southern Maine Community College or during a relationship with an abusive boyfriend who used drugs.

When Fred Smith started dating Ronni in 2012, she was already addicted to painkillers. He had been using pills himself since high school, when his father was diagnosed with cancer, and his drug use worsened after his father’s death the year he and Ronni started dating. He and Ronni considered their drug use recreational.

When Fred lost his job, he used the last of his money to buy Suboxone on the street. They weaned themselves off opioids, and Ronni became pregnant during their fragile sobriety.

“At that point, we didn’t realize the extent of our disease,” said Fred, now 25. “We were very excited, but we knew we had to make a lot of changes to have a child.”

Ronni did not use during her pregnancy, even though Fred did. The couple moved into her parents’ house. On April 15, 2014, Ronni delivered a healthy baby girl and named her Claire.

Ronni did not use during her pregnancy, even though Fred did. The couple moved into her parents’ house. On April 15, 2014, Ronni delivered a healthy baby girl and named her Claire.

When Ronni left the hospital, she was prescribed medication for postpartum pain. She had not told her parents or her doctors about her addiction, and she began using again. When the pills ran out, she and Fred bought heroin for the first time.

“We swore we weren’t ever going to do heroin,” Fred said. “All of a sudden, heroin was everywhere, and it was really cheap. We did it once, and that was just to get through. Then we did it again and again.”

They wanted to quit, but the withdrawals were crippling. They talked about finding a residential treatment program, but they worried they would be separated from Claire. Cheryl noticed when Ronni abruptly stopped breastfeeding, but her daughter denied there was any problem.

“We tried to stop numerous times,” Fred said. “We wanted to get help, but we felt like we couldn’t tell anybody. We were really worried about losing Claire and what people would think of us.”

It was Ronni, and not Claire, who was lost in the end.

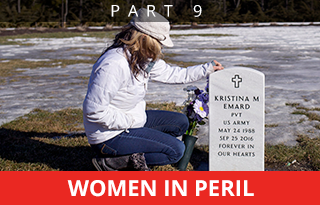

TELLING HIS DAUGHTER’S STORY TO STRANGERS

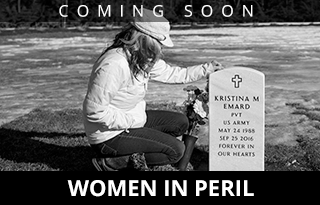

Matt Baker, a reluctant public speaker, has decided to tell the story of his daughter’s life and death at police training sessions and high school assemblies.

“The day after is depressing,” Matt said of these talks. “But if you keep the memories alive and the pain alive, it keeps the issue alive.”

Speaking before high school students at an assembly in Jay last month, Oxford County Sheriff’s Deputy Matt Baker of Stow shares the story of his 23-year-old daughter, Ronni, who died of an opioid overdose in his arms in 2015 after he tried to administer CPR. “I had to go downstairs,” he told them, “and I had to tell my wife that my daughter was dead upstairs and there was nothing we could do.” Staff photo by Brianna Soukup

So one February afternoon, he visited Spruce Mountain High School in Jay to tell 450 teenagers about the night Fred found her unconscious on the bathroom floor.

Matt performed CPR and felt a single heartbeat. Rescue workers gave her four doses of Narcan, an antidote to the effects of overdoses. Despite their efforts, Ronni died in her father’s arms.

“Then I had to change my role from a cop to a father,” Matt told his audience. “I had to go downstairs and I had to tell my wife that my daughter was dead upstairs and there was nothing we could do about it.”

Students were crying as Matt finished speaking, but his face was dry.

“The only thing I can ask is if you decide this weekend, next weekend or next year that you want to try this or you want to snort a pill, you think about Ronni,” Matt said to them. “Think about what I’ve gone through, and think about my granddaughter, who is never going to know her mom.”

The day after Ronni died, Matt and Cheryl went to court. They were afraid Fred’s drug use would endanger Claire, and they filed an emergency petition for her guardianship and a complaint for protection from abuse.

Across the state, addiction plays a growing role in these guardianship cases. Cumberland County Probate Court, the busiest in the state, handles 80 to 100 minor guardianships annually. The probate courts don’t compile case data, but judges and others say that in recent years, emergency petitions like the one the Bakers filed have become more common.

“It used to be that the parents couldn’t afford it, or they were getting divorced, or there was domestic violence,” said Cumberland County Probate Judge Joseph Mazziotti. “But there’s a clear movement away from what have been more traditional reasons for minor guardianships to addiction.”

In the first few months after Ronni’s death, Fred was allowed to see Claire only with supervision from his sister or the Bakers.

“That was hard for a while,” Fred said. “It was hard to even talk to them or even look at them. There was a lot of regret and guilt on my end, a lot of anger and blame on their end.”

Claire was too young to understand what had happened, but she noticed her mother was missing. The first few nights after Ronni’s overdose, she cried all night long.

‘CLAIRE IS AN INCREDIBLE HELP,’ DAD SAYS

Fred Smith is on probation for one year for his role in obtaining the drugs Ronni used to overdose. His daughter Claire lives with Ronni’s parents while Fred and his girlfriend, Nichole Schiller, live a couple of miles down the road from the Bakers in Stow. Staff photo by Brianna Soukup

Now, Fred and his girlfriend, Nichole Schiller, live just a couple of miles down the road from the Bakers. Claire greets Fred and Nichole with tight hugs as she arrives for an overnight visit.

“I missed you so much,” Nichole, 24, says.

“I missed you, too,” Claire replies.

Fred said he has not used drugs in two years. When Ronni died, he sought Suboxone treatment and counseling. Nichole is also in recovery, and they often attend Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous meetings together. They rented a home with a second bedroom for Claire. She now spends one afternoon and two nights a week with them.

VITAL SIGNS: The Maine Department of Health and Human Services removed 411 children from Maine homes where a parent’s drugs use put them at risk last year. That’s a 45 percent increase since 2009.

Fred is on probation for one year for his role in obtaining the drugs Ronni used. He wants to be more involved in Claire’s life as time goes on. The relationship between the Bakers and Fred has improved greatly over time, but they still worry about relapse.

“We’re not trying to hold onto her to keep her from him,” Cheryl said. “We’re older and wiser and know a lot more about this than we used to. It’s very easy to fall back into this. As long as we can hold onto her, we’re just giving him a little more time.”

For Fred, the most difficult days are those without his daughter. Every day, Nichole wears a pink Minnie Mouse ring Claire gave her.

“Claire is an incredible help,” Fred said. “She doesn’t know it. We would do anything for her. Anytime it gets hard and we start thinking about going back, it’s just Claire, think about Claire. She’s worth a clean life.”

As Claire gets older, her family is not sure how they will talk to her about addiction and Ronni’s death. For now, they are going about their lives. Cheryl makes entries in her granddaughter’s baby book, picking up where Ronni left off. The Bakers finished the paperwork Ronni started to set up Claire’s college fund. Someday, Matt will teach Claire how to hunt like he taught Ronni.

The ribbons Ronni won with her horses at 4-H fairs hang above the window in Claire’s room. A copy of Ronni’s memorial card sits on Claire’s dresser at Fred’s house, and Cheryl keeps another in her car.

Before she falls asleep in Ronni’s old room, Claire likes her bedtime routines. Once Cheryl has turned on the lullabies and the night lights, she reassures Claire her grandparents will check on her later.

“I love you,” Cheryl says.

“Everybody loves Claire,” the little girl says.

This story was updated at 4:09 p.m. April 13, 2017 after the Maine Attorney General’s Office revised its preliminary estimate of the number of drug overdose deaths in 2016.

Send questions/comments to the editors.