A man convicted 25 years ago of murdering a 16-year-old Portland girl was granted bail Thursday after a dramatic hearing in which the state’s star witness recanted her testimony and alleged that she was coerced by police to lie at the trial.

“This is only a bail hearing,” Justice Joyce Wheeler told Anthony Sanborn Jr. before announcing her decision in Cumberland County Unified Criminal Court. “So I cannot apologize to you. All I can say to you is that there is a reasonable likelihood of success (in overturning the conviction) and I will set bail.”

The key moment in the hearing came when Hope Cady, who testified in 1992 that she saw Sanborn kill Jessica L. Briggs on the Portland waterfront in 1989, told Wheeler that she wasn’t even on the waterfront the night of the murder. Sanborn’s lawyer, Amy Fairfield, also presented evidence that Cady has vision problems that might have made it difficult or impossible for her to see the murder even if she had been nearby.

Wheeler set bail at $25,000 cash or surety, and imposed standard conditions that Sanborn not leave the state, possess or consume drugs or alcohol, and that he check in weekly with police in Westbrook. His wife, Michelle Sanborn, owns a home there and Sanborn will live with her while the post-conviction review process goes forward.

Sanborn, who was serving a 70-year sentence for the murder, was released Thursday afternoon from the Cumberland County Jail to a waiting crowd of media and friends.

The development in Sanborn’s case is unprecedented in the state, according to exoneration data collected by the University of Michigan. No one convicted of murder in Maine has ever been exonerated, and although Sanborn’s conviction still stands, he has come closer than any other state prisoner to clearing his name.

“I’m very grateful to the current Attorney General’s Office and the judicial system that does care about justice,” said Fairfield, who has worked on the case for nearly a year after being assigned to it.

Fairfield said that with bail settled, the review process will now turn to whether Sanborn’s conviction should be overturned. If that happens, the state would have to decide if it wants to retry Sanborn, but with the prosecution’s star witness recanting her testimony and the passage of nearly three decades, Fairfield questioned whether the Attorney General’s Office would take the case before another jury.

WITNESS: POLICE THREATENED HER

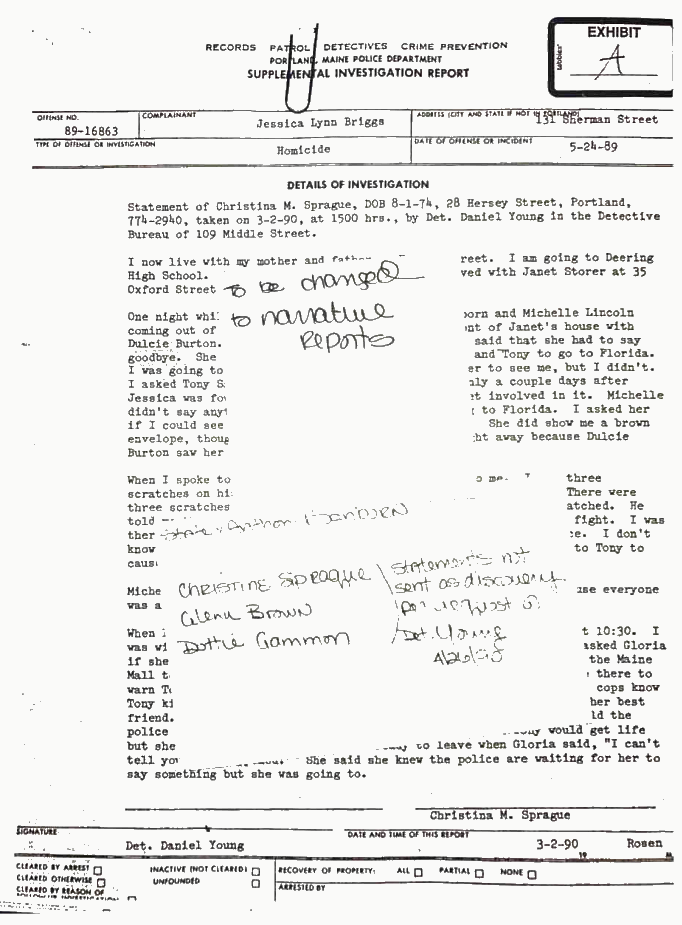

In court Thursday, Cady recanted the damning testimony she gave 25 years ago that identified Sanborn as Briggs’ killer and said she was instructed by detectives on how to testify. Cady had been identified as the only eyewitness to the crime. No physical evidence connected Sanborn to the scene, and the state’s case was entirely circumstantial.

Cady, who was 13 at the time of Briggs’ murder, was also legally blind when she claimed to have seen Sanborn commit the crime at the end of a dimly lit pier, but her vision problem was not disclosed to Sanborn’s defense team.

Cady said she was questioned at length at least 10 times by Portland police detectives James Daniels and Daniel Young, and that they threatened her with incarceration if she did not cooperate.

“They basically told me what to say,” said Cady, who now lives in Augusta. Cady said the detectives frightened her and suggested they would press charges in unrelated assaults and have her locked up for years if she didn’t testify as they instructed.

Anthony Sanborn reflects on his years in prison, and release on bail

At the time, Cady was a ward of the state, but she was questioned by detectives repeatedly for hours without her legal guardian or an attorney present, she testified Thursday. The detectives raised their voices, swore at her and called her names, she said.

Sanborn, seated nearby in the courtroom, frequently broke down in tears as Cady repeated that she was nowhere near the pier where the killing took place.

Wheeler suggested that police shouldn’t have questioned Cady without her guardian present, and also said prosecutors may have been unwise to proceed with a case based largely on such a young witness with vision problems.

Hope Cady testifies Thursday, casting doubt on testimony she gave in 1992 that identified Anthony Sanborn Jr. as 16-year-old Jessica Briggs’ killer. Staff photo by Ben McCanna

Confirming Cady’s recanted version of events was Margaret Bragdon, a former caseworker for the Maine Department of Health and Human Services.

Bragdon, now retired and living on Peaks Island, had been Cady’s state-appointed guardian and kept extensive notes on Cady and her health. The confidential narrative log she kept as part of her duties was not turned over to the defense team before Sanborn’s trial.

Bragdon said her notes from a 1990 interview showed Cady reported to her that detectives swore and yelled at her, and that as the trial neared, Bragdon said, Cady told her she feared the detectives and prosecutors and she was being told what to say.

Bragdon also said she was “more than surprised” that police did not contact her, as Cady’s guardian, to ask her what she knew.

Bragdon said she has come to believe that Cady didn’t witness the murder, but claimed she had because it was a “war story” that she believed would impress other street kids.

DETECTIVES DENY WRONGDOING

After the morning’s explosive testimony, Wheeler called a recess, saying she wanted to read new affidavits by then-Portland police detectives Young and Daniels, who opposed the bail motion and rebutted the allegations of misconduct.

In those affidavits, Daniels and Young, who are both retired, said they didn’t pressure or threaten witnesses or suppress any evidence.

In his affidavit, Young said he was offended by the suggestion that he didn’t turn over all the information police had to Sanborn’s lawyers.

“The reports I completed in this case are truthful (and) factual,” Young said. “There were no ‘secret deals’ or suppressed interviews in this case. Det. Daniels and I, along with the prosecutors, have professional standards and moral beliefs that were followed throughout this investigation.”

Assistant Attorney General Donald Macomber argued during Thursday’s hearing that bail should not be set for Anthony Sanborn Jr. Macomber was the secondary prosecutor in the murder case. Staff photo by Ben McCanna

Donald W. Macomber, the assistant Maine attorney general who was defending the conviction Thursday and opposing bail for Sanborn, indicated that Daniels and Young will testify when the hearing resumes in about two weeks.

Also Thursday, Fairfield submitted two affidavits from other witnesses in the original trial who said they lied on the stand under pressure from police and prosecutors.

“I was with the prosecutor a full day before the trial (and) she told me what to say,” Gloria Staples-Brosseau said in her sworn statement. “When I testified, I testified to what I was told to say by the prosecution and (detectives) Young and Daniels. I lied on the stand during Tony Sanborn’s trial.”

Another witness who had testified about Sanborn’s movements around Portland in the days before and after Briggs was killed also said in an affidavit that he lied under pressure by police.

Glenn Brown said the statement he gave police was “99 percent false,” including an allegation that he saw scratch marks on Sanborn’s face a few days after the murder. Brown said he couldn’t read or write at the time he was interviewed by police, so he couldn’t have read over the typed statement or signed it.

“Before I testified in court I was told by (former prosecutor and assistant Maine Attorney General) Pam Ames if I didn’t testify to the written statement, I would be charged with a crime,” so he lied on the stand, Brown said in his affidavit.

VICTIM’S FAMILY BELIEVES SANBORN GUILTY

Family members of Briggs, the victim, left quickly after Wheeler’s decision and could not be immediately reached for comment.

Before the hearing, Susan Briggs, the victim’s stepmother, said she was convinced of Sanborn’s guilt but that he deserved a hearing as part of due process.

Judge Joyce Wheeler granted bail for Anthony Sanborn Jr. after a key witness in his 1992 trial recanted her testimony Thursday. Staff photo by Ben McCanna

After hearing the testimony, but before Wheeler announced her decision, Briggs said the testimony presented Thursday struck her as contradictory and she still believes Sanborn is guilty.

“They have to convince me and they haven’t done that yet,” she said.

In a written statement, the Maine Attorney General’s Office said bail after a murder conviction is “highly unusual” and that the office will continue to fight Sanborn’s claims in court. Any decision on retrying Sanborn, the statement said, will depend on an assessment of the evidence.

In his final statement before the court recess, Macomber said that after Thursday’s hearing he will likely have to recuse himself from further proceedings because he has firsthand knowledge that Cady’s recantation was false.

Macomber was the secondary prosecutor assigned to the case, behind Ames, now a private attorney practicing in Waterville. He said he sat in on some of the interviews with Cady leading up to Sanborn’s trial, and suggested her allegations of police threats and intimidation were made up after-the-fact.

“This is obviously very serious allegations and we heard recantation of very important trial testimony,” Macomber said. “Ms. Cady never once came forward from 1992 to the present day to say that she was potentially committing perjury in October 1992. The petition obviously raises tremendous allegations and I would ask the court to defer ruling so the detectives and the assistant attorney general can explain themselves.”

Macomber said Ames had spoken with his office but could not prepare a written affidavit in time for Thursday’s proceeding. Previous attempts to contact her have been unsuccessful.

Anthony Sanborn Jr., with Ned Chester, one of his attorneys, was sentenced to 70 years in prison at his 1992 murder trial. 1992 Press Herald photo

Both of Sanborn’s attorneys at the time of his trial, Neale Duffett and Ned Chester, were in the courtroom Thursday, but they have declined to speak on the record about what occurred during Sanborn’s original trial, or their reaction to Thursday’s hearing.

Part of Fairfield’s argument is that Sanborn’s defense attorneys provided ineffective counsel.

Fairfield, in her response to Macomber, said it would be a miscarriage of justice for Sanborn to remain in prison.

“My burden here is, is there a likelihood of success?” Fairfield said of the post-conviction review process. “That is the state’s case – Hope Cady. So to keep this wonderful man in jail one second longer just perpetuates this miscarriage of justice. This stops now.”

Justice Wheeler urged Sanborn to meet with jail officials who can help him navigate a world that has changed dramatically since he was imprisoned nearly 30 years ago.

She counseled him to be patient and calm, even as she questioned Sanborn on how he was able “to maintain himself” during his time in prison.

She asked Sanborn if he had anything to say or had questions about bail.

Sanborn, smiling for perhaps the first time in his three hours in court, shook his head.

“No, I think I’m good,” he said.

Sanborn has maintained that he did not kill Briggs, whom he dated briefly for a few weeks before the murder in May 1989. Sanborn was convicted in 1992 and has been incarcerated at the Maine State Prison ever since.

In her motion for a review of the case, Fairfield included letters from volunteers and other inmates at the state prison who said Sanborn helps other inmates and doesn’t appear bitter over what he believes is a false verdict.

A SHOCKING CRIME

Jessica Briggs, murder victim

The crime was discovered on May 24, 1989, when Portland police were called to the Maine State Pier, which at that time was partially occupied by a Bath Iron Works floating dry-dock. Naval ships docked there regularly for maintenance, with sailors staying aboard the ships or in nearby barracks.

Near a dumpster at the end of the pier behind the BIW receiving department, police found a pair of black high-heeled shoes, a woman’s earring, a pack of cigarettes and a fresh pool of human blood. Drag marks pointed to an opening that led to the water. When divers pulled Briggs’ body from Casco Bay, they found her throat had been cut and she was stabbed multiple times and nearly disemboweled.

Sanborn and Briggs belonged to a rough-and-tumble group of teenagers living on the streets of Portland, staying with friends or at shelters, doing drugs and drinking, and trying to avoid the police. Like many of those teens, Briggs was a runaway from the Maine Youth Center, now called Long Creek Youth Development Center.

Sanborn had also been incarcerated at the youth center. At the time, police wanted him to testify as a witness to an earlier, unrelated murder, but he skipped town on the day he was scheduled to appear before a Portland grand jury.

Fairfield argues that Portland police focused on Sanborn from the start, even when there was no physical evidence connecting him to the crime scene, and before a single witness implicated him to police.

She has filed a raft of exhibits and excerpts from the transcript of the original trial, as well as documents, one of which purports to show written proof of the suppression of evidence by the state in a coordinated fashion.

Fairfield also has filed papers with the court indicating that a forensic profiler reviewed the case and will submit a written opinion describing how Briggs’ killing was likely premeditated by someone who had killed before, and did so out of a pathology that developed over time. The profiler ruled out Sanborn as the possible killer.

Matt Byrne can be contacted at 791-6303 or at:

mbyrne@pressherald.com

Twitter: MattByrnePPH

Send questions/comments to the editors.