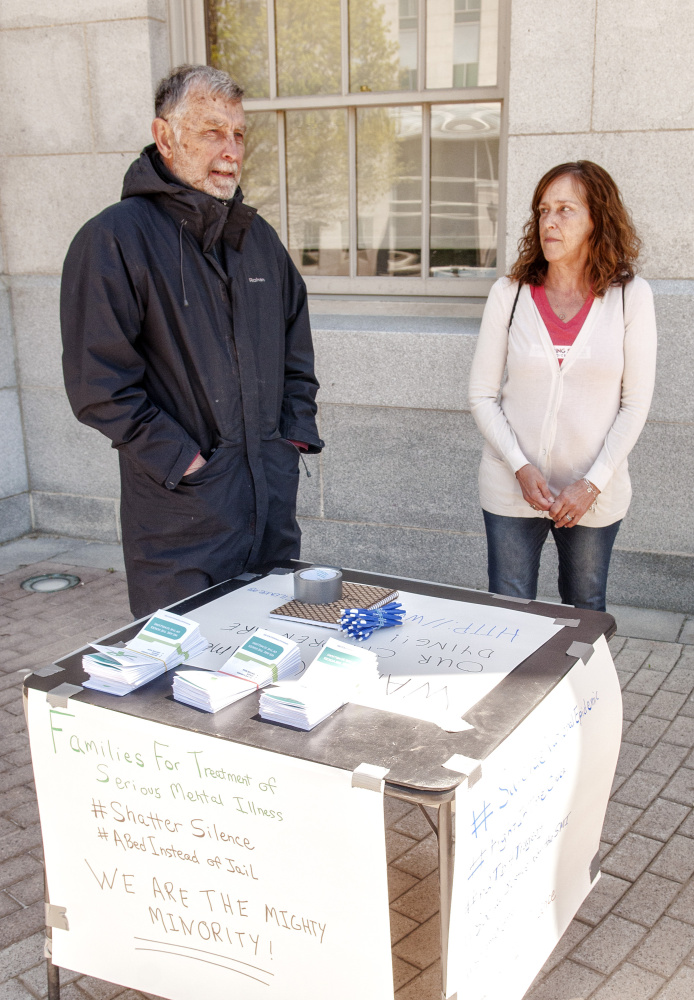

AUGUSTA — A small number of people came to the capital Saturday afternoon to try to raise awareness for the needs of people with severe mental illness.

Their gathering outside the State House was part of nationally coordinated event called Shattering Silence. In cities around the country, organizers were holding similar gatherings.

The Augusta event was organized by Jeanne Gore, a Shapleigh woman whose son is severely mentally ill and who in 2015 started an advocacy group for families facing similar challenges. The group is called Families for Treatment of Serious Mental Illness.

Gore’s son is in his mid-30s, she said, and has been hospitalized more than 40 times in the last 17 years.

Gore was joined at the Saturday gathering by several other parents-turned-advocates and by a few mental health workers. The event started at noon, and within the first half hour, about eight people came.

The challenge for parents like Gore, she said, is that the mental health care system has many holes, so there’s a shortage of opportunities for people like her son to get the care they need. The challenge is even greater because a small percentage of patients have a condition called anosognosia, which prevents them from recognizing their own illness and the need to take medication.

“There are no beds,” Gore said, referring to a shortage of inpatient programs. “There’s no treatment.”

For the severely mentally ill, that can lead to homelessness or violent behavior that lands them in the criminal justice system, said another parent who attended Saturday’s gathering, Chip Angell, of Brooklin.

Angell is no stranger to tragedy. His own son, Chris Angell, was an accomplished tennis player who suffered from paranoid schizophrenia and five years ago, at the age of 39, commit suicide. That was just one failure of the nation’s mental heath care system, he said, before offering a short history lesson.

Until the 1960s, much of the mental health care in the United States was delivered in large hospitals, but that decade, there was a movement to close the large hospitals, Angell said, reciting a common argument of people trying to reform the mental health care system. But there was never a corresponding replacement of those institutions with the community support services that would have benefited people like his son.

Gore has advocated for changes to the state’s mental health care laws. One victory, she said, was a law that passed in 2011 and created something called a progressive treatment program, which creates a team of support workers for certain patients.

That level of care has “saved my son,” she said.

But much more needs to be done, Gore and Angell said, both in Maine and across the country.

Charles Eichacker — 621-5642

Twitter: @ceichacker

Send questions/comments to the editors.