Honey Rourke remembers the last time she saw her mother, Pauline. Her mother was lying on her side in bed, not moving. Honey, who was 12, thought her mother was sleeping, so she kissed her on the back of the head and left for school.

When she got home from school that afternoon, her mother was nowhere to be found. She called out for her, but there was no answer.

Honey has not heard her mother’s sweet voice since that day 41 years ago when she disappeared forever from their mobile home in Fairfield Center.

Pauline Rourke probably was already dead when Honey gave her that last kiss.

Police now think that the Rourkes’ live-in distant relative, Albert P. Cochran, murdered Pauline Rourke, who was 32. Before he died at a Rockport hospital last month, Cochran, 79, told state police he knew Rourke’s remains were in a water well in the Smithfield area, though he never admitted directly that he had killed her, according to police.

But Honey Rourke, now 53 and living in Lewiston, is certain that Cochran, whom the family referred to as “Pat,” killed her mother. He already had killed two other women, although Honey would not have known that at the time.

Honey Rourke said she visited Cochran several times while he was serving a life sentence in Maine State Prison for murdering another woman, Janet Baxter, in 1976. He had served 18 years of that sentence when he died.

“I want people to realize he did this to her,” Rourke said in an interview.

Rourke said when she visited Cochran in prison, she kept a small state police tape recorder hidden among items in the room, including books, and asked him questions about her mother’s disappearance. He would play games sometimes and lie, but sometimes he would slip up and inject truths, including the time he said the water in the well was cold and he knew that because he put his hands into the water. State police would take the tape recorder after the visit ended, she said.

“He’d say three guys killed her and then he’d use the word ‘I’. He’d say, ‘I shot her.’ I was just in shock by what he said. He’d say he shot her in the head. He chuckled and said he was glad it wasn’t his mother.”

Rourke remembers having to leave the room for a while because what he said made her sick, but she knew she had to be nice to him to get him to continue talking.

Sometimes, Cochran would say cruel things about her mother, she said.

“He said, ‘I threw her over the Waterville-Winslow bridge.’ He even talked about the mattress she was on. I got mad and blew up at him.”

Detectives from the Maine State Police Unsolved Homicide Unit have worked intensely on the case and began increasing their visits with Cochran this year as his health deteriorated and it appeared his death was imminent. Cochran was at Pen Bay Medical Center in Rockport when he died June 27. He was serving a life sentence in the Maine State Prison in Warren for the rape and shooting death of Baxter, of Oakland, on Nov. 23, 1976.

Baxter’s killing happened more than two weeks before Pauline Rourke disappeared on Dec. 12 that year. Police in 1976 had not yet linked Cochran to Baxter’s murder. In 1998, 23 years later, they discovered that connection through DNA testing and arrested him. At the time, Cochran was married and living in Stuart, Florida.

LAST KISS

Honey Rourke has been married twice and has four children and 15 grandchildren. She has held on to hope for the last 41 years that her mother’s disappearance would be solved.

Honey was an only child and loved her mother. She remembers everything about her, she said.

“She was 20 when she had me. I had 12 good years with her and I have a lot of good memories. She taught me how to cook. By the time I was 4, I was making my own chocolate chip cookies. She taught me how to can; she taught me how to sew and knit. She was very artistic. She drew a lot. She took me out of school during a snowstorm — she told them I had a dentist appointment — and she took me sledding. She told me I was one of those kids who never missed school and I deserved a break. She was a Girl Scout leader — my Scout leader — and we did arts and crafts. I remember Friday nights eating tapioca pudding with her and watching movies.”

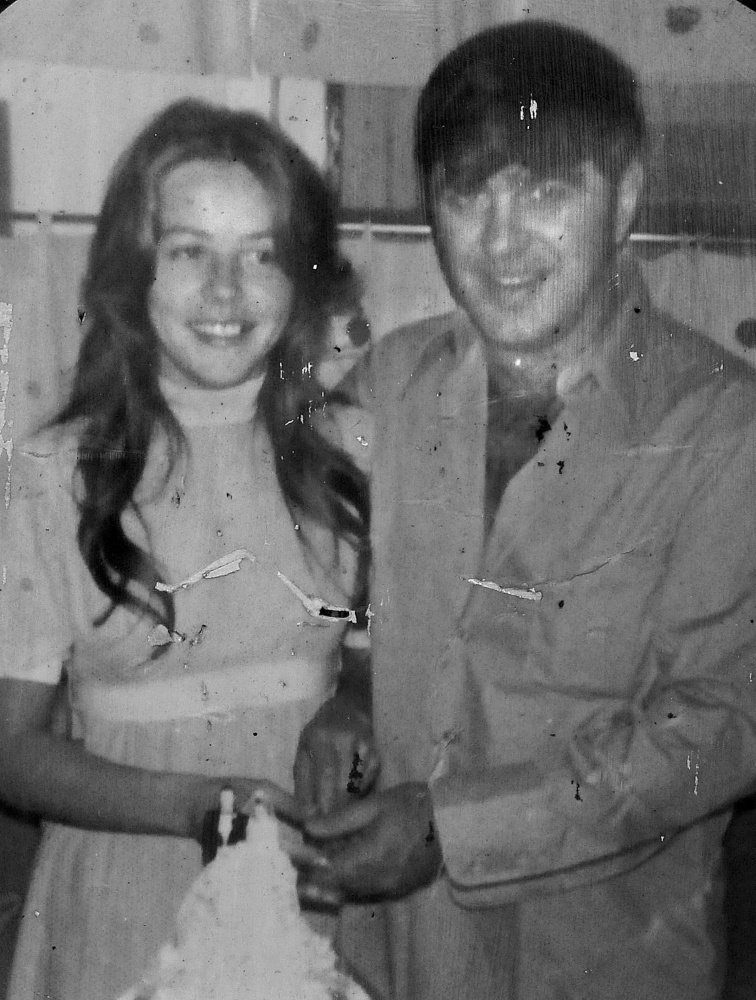

Pauline Rourke, shown in 1970, disappeared in 1976. Police think she was murdered by Albert P. Cochran, who died recently while serving a life sentence for the murder of Janet Baxter.

She said she did everything with her mother, who was tiny at 4 feet, 11 inches tall. That included gardening, and Rourke continues to garden. “At Christmas, she made homemade ornaments with popcorn and cranberries, and I taught my kids to do that, and they do it now,” she said.

Pauline Rourke had gone through nursing school and worked at Hilltop School on Quarry Road in Waterville, Honey Rourke recalled. Honey Rourke’s biological father was not part of their lives, as he and her mother did not get along and they had split early on, she said. When Honey Rourke was 7, her mother married a man from Waterville who became her stepfather, she said. While he was nice, he drank a lot and that caused problems in the marriage; so her mother wanted to take a break from him for a while, and that’s when they left, she said.

When Cochran returned to Maine from Illinois, he needed a place to live and so did the Rourkes, so Pauline Rourke rented the mobile home and Cochran moved in, agreeing to pay rent. The Rourkes and Cochran were distant relatives. When Pauline Rourke was a teenager, she had lived with the Cochran family in Oakland for a while, according to her daughter.

When Cochran lived in the mobile home, Honey Rourke was 12 and he and her mother were always fighting, she said. She said Cochran and her mother were not a couple, but he wanted her to be his girlfriend, and that is what they fought about all the time.

“I want people to realize he did this to her.”

— Honey Rourke

“The night before she disappeared, they had a huge argument,” Rourke recalled. “She was going to go back to my stepfather. I went to bed, listening to them arguing. I got up in the morning and she didn’t get up. She was in bed, laying back-to. I kissed the back of her head.”

After Rourke returned from school and could not find her mother, she later went to bed. Cochran woke her up at 11 p.m. and drove her to the home of his mother, Edith, in Oakland, and she went to sleep. Around 3 a.m., he woke her up and drove her back to their mobile home in Fairfield Center, where they got into a bad argument. Cochran insisted she do the dishes and she told him she did not want to because she was tired and had to go to school the next morning, Honey said.

“He had his hands right around my throat and I couldn’t breathe,” she recalled. “I kicked him where it counted and he left me alone. I think if I hadn’t kicked him where it counts, he would have killed me.”

It was the first time Cochran physically abused Honey Rourke, although she did not like him and her mother knew that, she said. “He was just a weird person to be around, and I kept telling my mother I didn’t like him.”

A couple of days after Pauline Rourke disappeared, her daughter was taken away to live out of state with relatives.

“My aunt came from Vermont, and I went with her to Vermont,” she said. “I was 12 years old. I didn’t want to think of my mother hurt, but at the same time, I knew she wouldn’t just ever leave me. We were exceptionally close.”

She said police believe Pauline Rourke was dead when she kissed her on the back of her head and then left for school.

Cochran already had had a sordid past by the time of the Baxter murder and Pauline Rourke’s disappearance.

Albert Cochran arrives March 21, 1998, at Portland International Jetport under police guard to face charges in connection with the 1976 killing of Janet Baxter. Cochran was convicted of the murder and is believed also to have killed Pauline Rourke, who disappeared soon after Baxter was killed.

Before the Baxter murder two weeks before Pauline Rourke’s disappearance, Cochran had served nine years in an Illinois prison for killing his first wife, Patricia Ann, 19 years old, in 1964 in Joliet, Illinois. He admitted having strangled her.

Their three children also were found stabbed to death in the bathtub, and Cochran told police his wife had killed them. He was never convicted in the children’s deaths.

Cochran had served only nine years of a 50-to-75-year sentence for Patricia’s murder and was on parole when Baxter was murdered.

Baxter, a nurse, had a cold and had driven into Waterville from Oakland on the evening of Nov. 23, 1976, to buy cough medicine at the A&P supermarket at JFK Plaza off Kennedy Memorial Drive. She never returned home. Her body was later found in the trunk of a car along the Kennebec River in Norridgewock. She had been shot in the head and chest.

Honey Rourke remembers Cochran seemed obsessed with Baxter’s murder and overheard her mother say to a relative that she was afraid Cochran might have been involved in the killing. It’s not clear whether Pauline knew about the killing of Cochran’s first wife in Illinois.

“She was scared and she didn’t know what to do,” Rourke said.

Cochran once drove Honey and Pauline Rourke from their Fairfield home to the crime scene, according to Honey.

“He wanted us to see where this happened,” she recalled in March 1998. “My mother thought that was real odd. From there on, the fighting got real bad between them.

“Then, all of a sudden, my mother disappeared.”

FOLLOWING LEADS

After Cochran’s death last month, Maine State Police reached out to the public for help in identifying water wells in the Smithfield area where Cochran might have dumped Pauline Rourke’s body 41 years ago.

Lt. Jeffrey Love, who supervises both the Unsolved Homicide and the Major Crimes units for state police, revealed for the first time last month that police had been visiting Cochran in prison for some time and even drove him to the Smithfield and Mercer areas to try to get him to show them the well he said Rourke’s remains were in.

Police excavated and searched wells but did not find her remains. Love said earlier this month that state police searched two more wells after receiving information from the public.

On Thursday, Love said police have not searched more wells since then.

“We have received more leads and followed up on more leads, and there will be more searches in the future that will be scheduled as we follow up on this information,” he said. “We are hopeful. Some of the information we’ve received has been very beneficial. We’ve been able to go out and search high-probability areas and eliminate them as possibilities.”

Love said the process is not easy, but police hope that, as they continue searching and eliminating possibilities, they will find what they are looking for.

This case, he said, is a good example of what the Unsolved Homicide Unit was developed for in an effort to help bring closure to the cases — and to the victims’ families.

Cochran told police that during the year before Pauline Rourke disappeared, he and Rourke were on the property where the well is located and Cochran stole two wagon wheels from the property, which also had a barn on it, according to state police Detective Jay Pelletier.

Honey Rourke walks on Wednesday in a park in Lewiston. Her mother, Pauline Rourke, disappeared in 1976, and police think she was slain by Albert P. Cochran, who died recently while serving a life sentence for the murder of Janet Baxter.

Honey Rourke recalls that many years ago, when Cochran was trying to find the wagon wheels for her mother, they went to a property where they saw some wheels, and she now thinks that could have been the place where he dumped her mother’s body in the well.

Rourke said she traveled with Pelletier, the state police detective, and the victim’s advocate to try to find that site. Cochran described the property as having a dilapidated barn on it that had caved in, Pelletier told the Morning Sentinel in late June. There was a well between the barn and the road on the property and the well was lined with slate rocks on top, according to Pelletier.

Rourke told the Morning Sentinel that she remembers her mother wanted two wagon wheels to put at the end of their driveway in Fairfield Center and she planned to place reflectors on them.

“Pat had a thing about taking my mother and I everywhere with him, even when my mother didn’t want to go places,” she said. “He insisted on it.”

She said that during the few months they lived with Cochran, they were afraid of him.

“I was very scared of him and I know my mother was scared of him — I could see it in her eyes and the way she was around him.”

CLOSE TO TRUTH

When police called Rourke in late June to tell her Cochran had died, she experienced a mix of feelings — relief and fear.

She worried that Cochran’s secret — the whereabouts of her mother — would never be revealed.

“I’m glad he’s dead, but I’m scared that he took that with him,” she said, choking up.

Rourke said her several visits to Cochran while he was in prison were hard, but she was on a mission to find answers. She would sometimes get upset at the things he said, but she knew she had to keep trying. After each visit, she would go home and get sick, she said.

“I couldn’t sleep for days. It would be horrible, and the final time, he wouldn’t tell me where her body was and I got mad. When I left, I was bawling my eyes out and I was afraid he would never tell.”

She had planned to visit him again, but she never got the chance.

He died at 8:45 a.m. June 27 after a long struggle with health problems.

“Like I told (a victim’s advocate), I never got to take him to a trial,” Honey said. “I just want people to realize he did do this. He talked about shooting her in the head and he talked about the water being cold in the well. I don’t know how it could be any clearer.”

She said she is grateful people have called police with leads and she hopes they will continue to do so. Police have said the water well could be in Smithfield, Mercer, Oakland or Fairfield.

The victim’s advocate and Pelletier have been good to her and supportive, and she believes they are as dedicated to finding her mother’s remains as she is, she said. Pelletier, she said, has been relentless in pursuing answers.

“I keep trying to tell Jay, if they don’t find her, it’s not that he hasn’t tried. He has tried harder than anybody. He has just not given up. I think it’s gotten into his brain and his heart and he just doesn’t want to let go of it.”

Throughout the years since her mother disappeared, Honey Rourke has mourned her loss. Sometimes she will be thinking about her and remember something she had forgotten. She wishes her mother had had a chance to grow old and to see her grandchildren.

Not knowing where her remains are has been hard, Rourke said.

“I just never got to say my goodbyes. I have a horrible time, knowing her remains are out there. I just want people to realize it’s very important for me to find her. I really need to have the closure.”

Should police meet with success, she will have a proper funeral for her mother, she said.

“I will have a funeral, but I won’t bury her again. I won’t put her in the ground. She was too young. I will just cremate her bones.”

Amy Calder — 861-9247

Twitter: @AmyCalder17

Send questions/comments to the editors.