SOUTH BERWICK — “The past is a foreign country,” British novelist L.P. Hartley famously observed, “they do things differently there.”

Hartley was writing of Britain at the dawn of the 20th century, but his observation is particularly true of early Maine and New Hampshire, two scrappy and struggling colonies sandwiched between Wabanaki Indian lands claimed by the King of France and the dour Puritans’ commonwealth of Massachusetts, two far more powerful rivals who would each seek to obliterate them.

Yet the experiences of this early period – the 17th century – permanently shaped the culture, economy and society of New Hampshire and, especially, Maine, huddled next to each other on a swath of coast extending 20 miles in each direction from the Piscataqua River. Both were, for much of this era, religiously diverse, loyal to the crown and deeply opposed to the Puritans’ culture and political goals, even after each was forced into Massachusetts’ expanding empire-within-an-empire in the 1640s and 1650s.

They were colonies of a colony, chafing under an alien and sometimes oppressive regime, exposed to wars not of their choosing, their development retarded by intended and unintended consequences of Boston’s imperial rule, which didn’t come to a formal end in Maine until 1820. Even in northern New England, few people are aware of this background, despite how much it shaped our modern-day experiences.

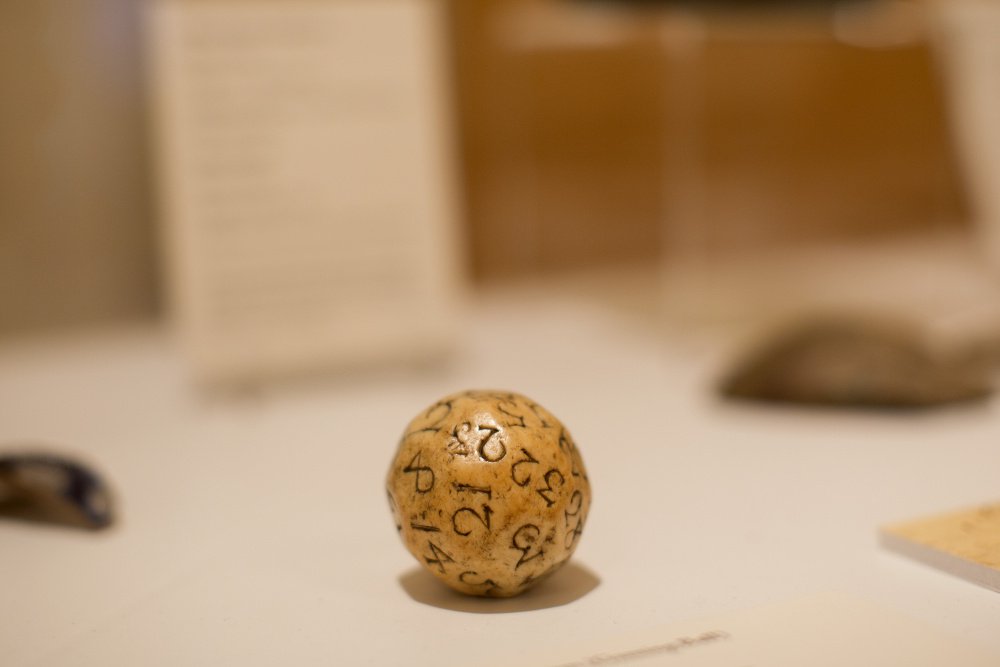

An ambitious exhibit at South Berwick’s Counting House Museum is helping to change that, pushing this formative period in our history into the spotlight. “Forgotten Frontier: Untold Stories of the Piscataqua,” open from 1 to 4 p.m. weekends through October, explores the turbulent era with the help of a treasure trove of period artifacts excavated from the remains of sawmills, taverns, farmhouses and ships buried beneath the backyards and woodlots of southern Maine and Seacoast New Hampshire.

“People have, at best, these crude stereotypes that if anybody was living here in the 17th century they were dour and stern Puritans dressed in black and white, but in reality there was this rich, vibrant and diverse culture that’s, to some degree, reflective of today: a region of newcomers and native peoples trying to live together, interact and build a new community,” said Emerson Baker of Salem State University, a historian of early Maine and New Hampshire who helped organize the exhibition.

This diverse and decidedly un-Puritan area resulted from being controlled by two feudal-minded English landlords, Sir Ferdinando Gorges (the founder of Maine) and John Mason (father of New Hampshire), both of whom were, like their king, hostile to the Puritans, their ideas and their claims to be creating a more godly society.

Unlike Massachusetts – where one had to pass a test of religious conformity to become a citizen – settlers in these colonies were Anglican, Quakers and Baptist. There were dozens of Highland Scots, who were prisoners of war banished here after the Battle of Dunbar, as well as Irish children in indentured servitude and a scattering of African slaves.

Even the English population tended to be from the West Country, a very different milieu than East Anglia, from which many of the Massachusetts Puritans came. They were accustomed to living in scattered estates, not nucleated villages, which made for a very different settlement pattern in Maine and New Hampshire, and were much more likely to support the royal authority and the “old ways” of doing things in the face of modernizing, quasi-capitalist pressures from London and the east of England. Kittery is named for Kittery Court, the Devon manor of the Shapleighs, one of the founding families.

The South Berwick exhibit tells the region’s story via the lives of eight representative residents, from the local Wabanaki sachem (or “chief”) and the keeper of a rowdy Quaker tavern to the slave Will Black – whose descendants helped settle Orr’s and Bailey Islands here in Maine – and Mehitable Goodwin, who spent years in servitude in distant Quebec after being captured by Indians allied with France.

Among the artifacts on display is a Tudor rose medallion, a Royalist symbol worn in defiance of the very un-Royalist Massachusetts authorities during the decades after the English Civil War when New Hampshire and Maine were both annexed by Boston.

“This was an overt statement, like wearing an American flag in our lapels,” said Baker. “This is a family saying, ‘We are Anglicans and loyal to the crown and to hell with you in Massachusetts.’ But at the same time, too, they would do business with them, of course.”

Relations with native inhabitants were relatively cordial in the first half-century after colonization, but the situation deteriorated after Massachusetts annexed the region in the 1640s and 1650s, triggering a series of brutal wars between the 1670s and the 1760s, during which many of the colonists’ homesteads and settlements were repeatedly destroyed.

“We associate this place with resilience and stubbornness and independence, and that all has its roots in the 17th century,” said the exhibit’s curator, Nina Maurer. “When you’ve seen your parents’ generation decimated and building a home is an uncertain undertaking, it can mark a place in ways we think you can still see.”

The Old Berwick Historical Society, which runs the Counting House Museum and raised over $100,000 to launch the exhibit, is hosting a related lecture series and history hikes this fall.

On Sept. 28, Dr. Linford Fisher of Brown University will speak on the complex interactions between Native Americans, northern New England settlers and the Atlantic slave trade at 7:30 p.m. at Berwick Academy.

Wabanaki scholar Lisa Brooks of Amherst College will take up the meaning of one of the most brutal of the Anglo-Wabanaki Wars on Oct. 26 at the same time and venue. (More information at oldberwick.org.)

The exhibit will be on display throughout the museum’s 2018 season as well.

“The 17th century tells us something about the struggle for dominance and control and the destiny of a landscape, one where people had to make choices,” Maurer said. “Those are challenges we still have today.”

Colin Woodard is the state and national affairs writer for the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram and the author of “The Lobster Coast: Rebels, Rusticators, and the Struggle for a Forgotten Frontier.” He can be contacted at 791-6317 or at:

cwoodard@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.