While the state Department of Education pushes plans to regionalize services, local educators are not sure what that will mean for school districts as they are now organized.

Several Maine school districts are pursuing efforts to pool resources and regionalize services such as transportation, special education and technological education through grants and selective pilot programs under the auspices of the state Department of Education.

State officials say the regional service centers model should maximize efficiencies and provide more opportunities for students. While local educators agree that collaboration makes sense, they are unsure of exactly what those service centers will look like.

This model will be in the spotlight at a workshop sponsored by the Maine School Management Association and the law firm of Drummond Woodsum. The workshop, scheduled for Friday, Sept. 8, at the Augusta Civic Center, will delve into new state law that authorizes the creation of “school management and leadership centers,” or regional service centers.

“The ultimate goal is to increase opportunities for students and find ways to be more efficient in the management of school districts,” said Mary Paine, director of special projects within the state department. “The end goal is not just savings.”

ORGANIZATIONAL CHANGES

Some districts are considering dissolving their current organizational structure to form regional service centers that would receive state subsidies for administrative work. Among them is Waterville-based Alternative Organizational Structure 92. The district-wide board voted to study the feasibility of dissolving the AOS structure and creating three systems instead, most likely creating a regional service center in Waterville.

Districts can remain intact and still be members of a regional service center, but no matter what, they will all lose a state allocation for system administration, or superintendents, within the next three years, according to Suzan Beaudoin, deputy commissioner of the Department of Education. That money is being phased out to instead go toward instruction, Beaudoin said.

Any other savings that result from regionalization are intended to go toward new opportunities for students, Paine said.

But if a district becomes a service center, it would get a different allocation for administrative costs, like the business office and legal costs. The state would also pay 55 percent of the salary of the center’s executive director, who could double as a superintendent, as well as the full costs of the accounting, payroll and student information systems.

Local school systems could keep or hire superintendents, but “the state won’t participate in that cost,” she said.

Other districts are applying to form what the state is calling “integrated, consolidated 9-16 education facility pilots,” with the preferred pilot combining three or more high schools and creating a new governing school board for a new regional high school partnered with a career and technical school, the University of Maine System and the Maine Community College System. The department chose three out of seven original applicants statewide to continue onto phase two of the application.

The details of what those projects will look like are being worked out now, according to Rachel Paling, director of communications for the Department of Education.

QUESTIONS RAISED

The department envisions nine to 12 regional service centers throughout the state, though Beaudoin said it will take a long time to get there.

The state is starting this venture now because the “circumstances are more favorable,” she said.

About one-third of superintendents in the state will reach retirement age over the next five years, and most districts are experiencing declining enrollments.

“It’s not all about efficiency” though, she said. It’s also to help the districts that are poor or rural that “just can’t do things alone, but together they can.”

“The mills closing has changed the dynamics in some of these areas,” Beaudoin said.

Eric Haley, AOS 92 superintendent, said he thinks the idea makes sense, but he’s still waiting for further information from the state.

“We’re kind of just groping in the dark about what these regional service centers are,” he said.

With the information he has now, Haley said it seems like the service centers would work like AOS 92, which consolidates much of its administrative work under Waterville schools.

“I’ve got one person doing accounts payable for three school systems” for example, he said. “I think we’ve demonstrated that we can do an efficient job with less people. This isn’t a new concept.”

Carl Gartley, superintendent of Oakland-based Regional School Unit 18, said that cutting administration might not be in the best interest of Maine schools.

“I think in Maine administration is part of the instruction for the students. What we do and what our principals do in their buildings is very much hands-on,” he said.

Still, Gartley is willing to look at regionalization, which he said schools in central Maine have done for some time but could do on a larger scale. He questioned whether this approach would work in other areas of the state, though, as there are some areas where districts are spread far apart.

“On paper, some of this looks good,” Gartley said. “But I think there’s a lot of details that need to be considered.”

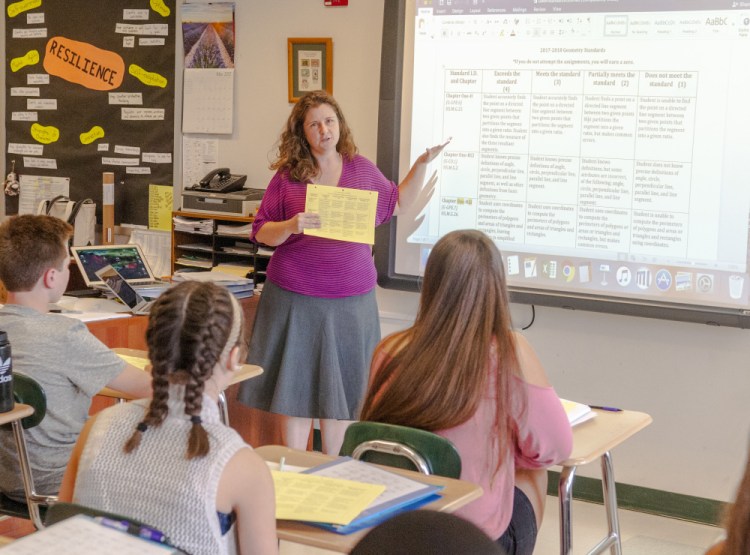

Amanda Boyce teaches Honors Geometry class Thursday at Winthrop High School.

COLLABORATIVE PROJECTS

The state has already awarded 10 grants for collaborative projects between schools and other agencies as it begins to roll out its campaign for regionalization, dubbed EMBRACE: Enabling Maine students to benefit from regional and coordinated approaches to education.

The Western Maine Educational Collaborative, a nonprofit organization representing 14 school systems, including Farmington-based Regional School Unit 9 and Winthrop Public Schools, is involved in one project that aims to create a professional development program for high school teachers throughout its districts.

The collaborative had prior success with a similar program called the Maine Mathematics Coaching Project, which focused on kindergarten through eighth grade. It hopes to use this grant opportunity to “scale it up” and provide similar support to teachers in high schools, according to Executive Director Kristie Littlefield.

For this project, educators from the district will work with the University of Maine at Farmington to become math coaches through either a math leadership certificate program or graduate-level courses paired with additional training and site visits. When their training is complete, these educators will be able to “coach” or mentor other teachers to improve math instruction and, ultimately, student outcomes.

The educators will also have time to discuss what the coaching model will look like at their district with administrators, as the districts all vary in size.

The teachers are also forming a “professional learning community,” Littlefield said, where they will have each other for support and collaboration throughout the process.

A number of schools involved in the collaborative also received a grant to develop a regional education program to serve students K-12, who are in need of a “therapeutic education setting.” The collaborative itself is not involved, however.

The proposed program will include “family work” and “community collaboration” to support students, while maintaining a goal of reintegration with nondisabled peers.

Other projects throughout the state include the Kennebec Valley STEM Collaborative Outreach, which will combine resources at the middle level to expand STEM (or science, technology, engineering and math) studies and serve all students, and the Sheepscot Regional Education Program, which will provide a single site for special education services for middle and high schoolers who need behavioral support, and who would otherwise be placed further outside their district.

Formulas are written on the board as Amanda Boyce teaches honors geometry Thursday at Winthrop High School.

MORE INFORMATION NEEDED

Like Haley, Littlefield is also waiting for more information from the Department of Education.

“I’d like to learn about what the state intends with these centers,” she said. “I don’t think I know enough yet to be able to form an opinion.”

However, she said that any time rural districts can get more state funding to meet their unique needs is a good thing.

Finding resources and cost-saving opportunities together is something that the Western Maine Educational Collaborative prides itself on, she said. The collaborative formed in 2005 and has been successful in sharing services and pooling resources regionally.

One barrier to regional services is the geography of Maine, but the organization has used technology when necessary.

“Maine is a big small state,” Littlefield said. “What we have found is that technology is an absolutely wonderful resource and tool … But it is not a total substitute for the face-to-face interactions.”

State officials hope that regionalization will be a way to “break down some of the barriers students have when accessing higher quality programs,” such as geography, said Mary Paine, the director of special projects. “It’s a challenge and a constant conversation.”

Rural districts are still looking to provide more services, just like those in more urban areas, she said.

Sara Landry, principal of Winthrop High School, which will be participating in the program to train math coaches, said that when it comes to professional development, regionalization is helpful.

“Teachers are learners as well, so as learners we continuously want to grow in our craft,” Landry said. “Anytime you allow teachers time to collaborate with one another and grow in their profession, that’s going to be a positive influence on both the teachers and the students that they serve.”

As for whether regionalization of other services, like special education or transportation, would work as well, she said she didn’t know.

“I know there are a lot of districts in Maine that don’t have the resources that they need because they don’t have the funding that they need to support their students,” she said.

Madeline St. Amour — 861-9239

mstamour@centralmaine.com

Twitter: @madelinestamour

Send questions/comments to the editors.