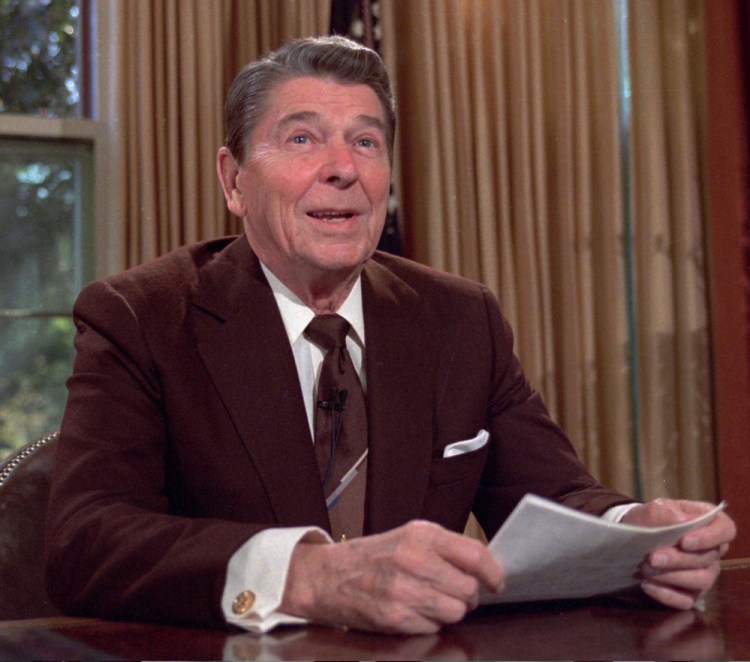

Four decades ago, while working for Rep. Jack Kemp, R-N.Y., I had a hand in creating the Republican tax myth. Of course, it didn’t seem like a myth at that time — taxes were rising rapidly because of inflation and bracket creep, the top tax rate was 70 percent and the economy seemed trapped in stagflation with no way out. Tax cuts, at that time, were an appropriate remedy for the economy’s ills. By the time Ronald Reagan was president, Republican tax gospel went something like this:

• The tax system has an enormously powerful effect on economic growth and employment.

• High taxes and tax rates were largely responsible for stagflation in the 1970s.

• Reagan’s 1981 tax cut, which was based a bill, co-sponsored by Kemp and Sen. William Roth, R-Del., that I helped design, unleashed the American economy and led to an abundance of growth.

Based on this logic, tax cuts became the GOP’s go-to solution for nearly every economic problem. Extravagant claims are made for any proposed tax cut. Wednesday, President Donald Trump argued that “our country and our economy cannot take off” without the kind of tax reform he proposes. Last week, Republican economist Arthur Laffer said, “If you cut that 1/8corporate3/8 tax rate to 15 percent, it will pay for itself many times over. . . . This will bring in probably $1.5 trillion net by itself.”

That’s wishful thinking. So is most Republican rhetoric around tax cutting. In reality, there’s no evidence that a tax cut now would spur growth.

The Reagan tax cut did have a positive effect on the economy, but the prosperity of the ’80s is overrated in the Republican mind. In fact, aggregate real gross domestic product growth was higher in the ’70s — 37.2 percent vs. 35.9 percent.

Moreover, GOP tax mythology usually leaves out other factors that also contributed to growth in the 1980s: First was the sharp reduction in interest rates by the Federal Reserve. The fed funds rate fell by more than half, from about 19 percent in July 1981 to about 9 percent in November 1982. Second, Reagan’s defense buildup and highway construction programs greatly increased the federal government’s purchases of goods and services. This is textbook Keynesian economics.

Third, there was the simple bounce-back from the recession of 1981-82. Recoveries in the postwar era tended to be V-shaped — they were as sharp as the downturns they followed. The deeper the recession, the more robust the recovery.

Finally, I’m not sure how many Republicans even know anymore that Reagan raised taxes several times after 1981. His last budget showed that as of 1988, the aggregate, cumulative revenue loss from the 1981 tax cut was $264 billion and legislated tax increases brought about half of that back.

Today, Republicans extol the virtues of lowering marginal tax rates, citing as their model the Tax Reform Act of 1986, which lowered the top individual income tax rate to just 28 percent from 50 percent, and the corporate tax rate to 34 percent from 46 percent. What follows, they say, would be an economic boon. Indeed, textbook tax theory says that lowering marginal tax rates while holding revenue constant unambiguously raises growth.

But there is no evidence showing a boost in growth from the 1986 act. The economy remained on the same track, with huge stock market crashes — 1987’s “Black Monday,” 1989’s Friday the 13th “mini-crash” and a recession beginning in 1990. Real wages fell.

Strenuous efforts by economists to find any growth effect from the 1986 act have failed to find much. The most thorough analysis, by economists Alan Auerbach and Joel Slemrod, found only a shifting of income due to tax reform, no growth effects: “The aggregate values of labor supply and saving apparently responded very little,” they concluded.

The flip-side of tax cut mythology is the notion that tax increases are an economic disaster — the reason, in theory, every Republican in Congress voted against the tax increase proposed by Bill Clinton in 1993. Yet the 1990s was the most prosperous decade in recent memory. At 37.3 percent, aggregate real GDP growth in the 1990s exceeded that in the 1980s.

Despite huge tax cuts almost annually during the George W. Bush administration that cost the Treasury trillions in revenue, according to the Congressional Budget Office, growth collapsed in the first decade of the 2000s. Real GDP rose just 19.5 percent, well below its ’90s rate.

We saw another test of the Republican tax myth in 2013, after President Barack Obama allowed some of the Bush tax cuts to expire, raising the top income tax rate to its current 39.6 percent from 35 percent. The economy grew nicely afterward and the stock market has boomed — up around 10,000 points over the past five years.

Now, Republicans propose cutting the top individual rate to 35 percent, despite lacking evidence that this lower rate led to growth during the Bush years, and a drop in the corporate tax rate to just 20 percent from 35 percent. Unlike 1986, however, this $1.5 trillion cut over the next decade will only be paid for partially by closing tax loopholes.

Republicans’ various claims are irreconcilable. One is that the rich will not benefit even though it is practically impossible for them not to — those paying the most taxes already will necessarily benefit the most from a large tax cut. And there aren’t enough tax deductions, exclusions and credits benefiting the rich that could be abolished to offset a cut in the top rate.

Even if they had released a complete plan — not just the woefully incomplete nine-page outline released Wednesday — Republicans have failed to make a sound case that it’s time to cut taxes.

Nor have they signaled that they’ll commit to a viable process. It’s worth remembering that the first version of the ’81 tax cut was introduced in 1977 and underwent thorough analysis by the CBO and other organizations, and was subject to comprehensive public hearings. The Tax Reform Act of 1986 grew out of a detailed Treasury study and took over two years to complete.

Rushing through a half-baked tax plan, in the same manner Republicans tried (and failed) to do with health-care reform, should be rejected out of hand. As Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., has repeatedly and correctly said, successful legislating requires a return to the “regular order.” That means a detailed proposal with proper revenue estimates and distribution tables from the Joint Committee on Taxation, hearings and analysis by the nation’s best tax experts, markups and amendments in the tax-writing committees, and an open process in the House and Senate.

There are good arguments for a proper tax reform even if it won’t raise GDP growth. It may improve economic efficiency, administration and fairness. But getting from here to there requires heavy lifting that this Republican Congress has yet to demonstrate. If they again look for a quick, easy victory, they risk a replay of the Obamacare repeal fight that wasted so much time and yielded so little.

Bruce Bartlett was a domestic policy adviser to President Ronald Reagan. He is the author of “The Benefit and the Burden: Tax Reform – Why We Need It and What It Will Take.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.