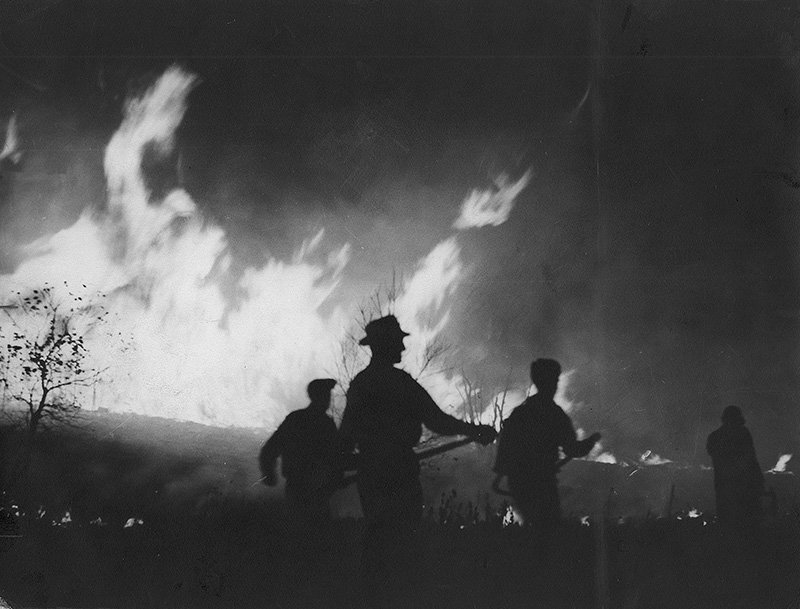

The walls of flames roared like tornadoes or locomotives across Maine’s wooded hillsides, devastating communities with a ferocity that didn’t distinguish between waterfront mansions or humble farmsteads.

The only difference was the size of the rubble and ash piles left behind when the fires of October 1947 finally ended.

In tiny Newfield near the Maine-New Hampshire border, 80 percent of the town’s land area burned, along with 40 houses, the town hall, two schools and the post office.

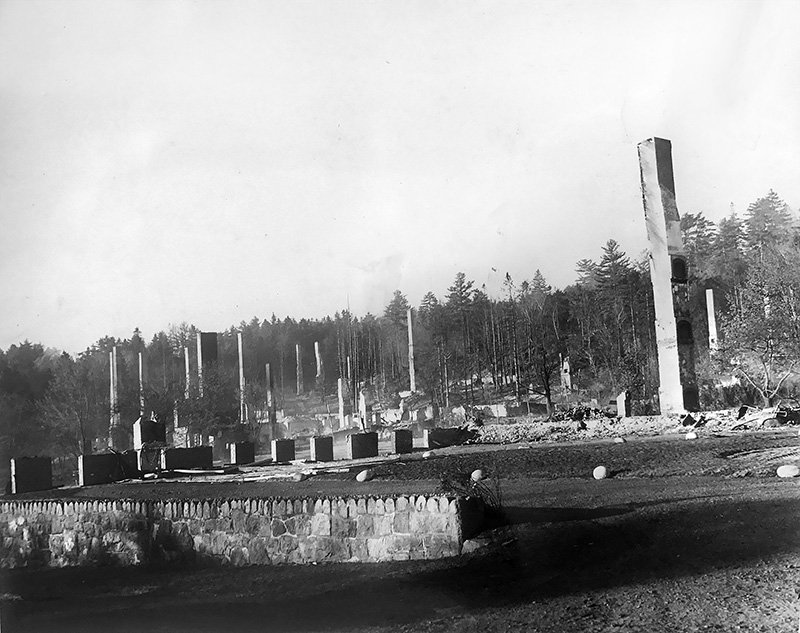

Kennebunkport’s Goose Rocks Beach community was reduced to a forest of chimney stacks.

While half of Acadia National Park burned, downtown Bar Harbor was only spared by a last-minute shift in winds and the heroic efforts of hundreds of firefighters.

The forest fires that swept across Maine 70 years ago this month were like nothing its residents had seen before, or thankfully since.

Newsreel courtesy of Northeast Historic Film

Hampered by antiquated equipment and little to no communication lines between teams, tens of thousands of men fought against wind-driven infernos so hot that church steeple bells melted while trees and houses exploded rather than burned. Women made untold amounts of sandwiches, chowders and coffee for roving bands of volunteer firefighters, even as they prepared to flee with their children should the flames arrive on their street.

By the time rains finally fell on Oct. 29 – weeks after flames began popping up across the drought-stricken state – the fires had burned more than 200,000 acres, destroyed nearly 900 year-round homes, 400 seasonal houses and left an estimated 2,500 people homeless.

That puts the 1947 fires on the same geographic scale as those that have ravaged northern California this fall, although the fires on the West Coast have claimed far more lives than the historic Maine fires.

Nine entire communities were “practically wiped out,” a Maine forestry official wrote a year later.

Newfield immediately after the fire. Press Herald file photo

Sixteen people lost their lives – a shockingly low number given the scale of the devastation and the thousands of untrained volunteers battling fast-moving fires with shovels and hand-pump water cannisters.

“It was one of those things: you don’t think about it, you just do it,” said Richard Neal, who as a 16-year-old Sanford resident joined the hordes of men attempting to slow the fires’ spread in York County.

The fires of 1947 are more than just a historical footnote, however. They forced major changes to how Mainers prepared for and responded to forest fires and inspired the creation of a cross-border firefighting compact that continues today.

The destruction also permanently changed two entire regions: Oxford and York counties and Mount Desert Island.

Seventy years later, the physical scars of the 1947 fire have been erased or lie hidden beneath layers of younger topsoil. Yet subtle evidence of the conflagration can be found throughout York County, where some villages that date back to the 1700s have a distinctly post-World War II feel.

“If you go up to Brownfield or Waterboro, there are not a lot of old houses,” said Steve Spofford, town historian for Kennebunk. “Those are two towns that had to build again basically from scratch.”

‘RACE OF TERROR’

After a wet winter and spring, the rains stopped falling over much of Maine around mid-July. They wouldn’t return until November.

“Continued days of warm, drying, gentle winds from the southwest and northwest quarters began to have a marked effect upon the soil moisture, wells, lakes, streams, ponds and vegetation,” Austin Wilkins, Maine’s deputy forest commissioner, wrote the following year. “By the first of October, with no break in the drought, several danger signs became very real and threatening.”

Reports of small fires sparked by cigarettes, road crews and unknown circumstances began pouring into state fire warden offices. Concerned about the growing fire threat, the state reopened fire towers during the second week of October and, on Oct. 17, Gov. Horace Hildreth closed most woods to hunting.

By Oct. 20, there were 50 small fires burning around the state. But things exploded a day later when strong winds fanned the flames beyond the fire lines, beginning what Wilkins dubbed “the race of terror” that would continue unabated for nearly a week.

Thousands of acres had already burned, but on Oct. 20-21 the danger of the forest fires became very real for many residents of southern Maine.

In North Kennebunkport, a days-old fire rekindled and grew into a rolling inferno. Flames leapt across Route 1 in the treetops – the moment captured by Associated Press photographer Ted Dyer – and churned toward Kennebunkport’s coastal villages as firefighters watched helplessly from below.

In this, possibly the most famous photo of the 1947 fires, a fire that had been underground at North Kennebunkport for almost a week broke out and began to move. Late in the day, fanned by high winds, the fire leaped across Route 1 in an arc of flames that dwarfed firefighters who stood helplessly by. Associated Press/Ted Dyer courtesy of the Brick Store Museum, Kennebunk

In her 1979 book, “Wildfire Loose: The Week Maine Burned,” author Joyce Butler captured the terror of women and children caught in Kennebunkport’s Goose Rocks Beach community as the wind-driven flames suddenly converged on the area.

The fire “roared into the beach settlement, a maelstrom of wind, smoke and flames,” forcing the group of women and children onto the beach and into the water, Butler wrote. Terrified wildlife also flocked to the beach, further unsettling the women, children and pets.

“They wrapped themselves in blankets, first a dry one, then a wet one, and waited, praying, trying to keep their spirits up, reassuring the children, worrying about their men who were off trying to save cottages,” said Butler, who interviewed dozens of fire survivors for her landmark book.

“When the women came out from under their blankets to see what was happening, they held wet pillowcases over their noses and mouths so they could breathe,” Butler wrote in “Wildfire Loose,” which has been re-released in paperback. “They could see that trees were burning from the top, not the bottom, flames in the green pines and the copper-colored leaves of the oaks. They heard the breaking of branches, and now and again an explosion as fuel oil tanks caught fire. Branches and burning shingles were dropping on the beach, carried there by the wind, which was now a gale.”

The majority of Goose Rocks Beach’s oceanfront houses burned before the flames headed up the coast toward Cape Porpoise and into Biddeford. Weeks later, the Kennebunk Star would publish a list – by name – of 182 houses that were destroyed in Kennebunkport, including at least 33 in Cape Porpoise.

Sheila Meek, now 82, remembers seeing the devastation after the fires were gone.

“It was an absolute mess, especially as you headed over toward Goose Rocks,” Meeks recalled recently. The summer home Meeks’ family rented in Cape Porpoise was among more than a dozen houses that burned on Crow Hill – a hill now dominated, perhaps fittingly, by a large water tower.

“It took a good, long time before things got built up enough and you didn’t see any reminders” of the fire, said Meek, who now lives in Kennebunk and is an archivist with the Kennebunkport Historical Society. “And there are some areas that never did get built up again.”

HOUSES ‘EXPLODED’ IN FLAMES

Tuesday Oct. 21 was bad. But the 23rd would become known as “Red Thursday” because of the devastation wrought.

Gale-force winds (some gusting toward hurricane strength at sea) fanned fires in York, Oxford and Hancock counties into uncontrollable conflagrations that changed directions in an instant. Families already on alert had just enough time to grab their prepacked bags and a few sentimental or valuable items before fleeing down flame- and smoke-choked roads.

An unknown house on fire. Observers of the various fires noted that house often seemed to just explode. Courtesy of the Brick Store Museum, Kennebunk, Maine

The night sky in Lyman was so bright that Sandra Caron remembers helping put her younger siblings to bed by the glare of the forest fires over the horizon.

Caron’s father, a potato farmer, had been off fighting fires for about a week, returning every few days to shower and catch a little sleep. Her mother made doughnuts for the Red Cross while she, the eldest child at age 10, was responsible for dousing any embers that drifted into the yard. But when the evacuation call finally came, Caron’s mother packed the bags, finished her last batch of doughnuts and loaded the kids into the car.

“We went down the dirt road with fire on both sides,” Caron recalled recently. “The smoke was very heavy and my mother would stop every once in a while to make sure she was still on the road.”

They stayed with a relative in Sanford for about a week but were relieved to learn their farmhouse survived thanks to a neighbor who kept wetting it down with buckets and a hose. Another neighbor’s house burned, as did numerous others in Lyman.

Some farmers didn’t even have time to release their animals from the barns. Others who did lost their livestock anyway.

In Brownfield, 75 percent of the taxable property burned.

Esther Boynton, in one of nearly two dozen interviews recorded by Butler, recalled the agonizing decision about what to take and what to leave behind when it was clear her family’s Brownfield house was “doomed.” Speaking 30 years later, Boynton regretted taking so many “good things” – i.e., valuables – and leaving behind the “ordinary things” you need for everyday life.

“I went out and I didn’t even close the doors behind,” Boynton said in a pained voice. “It didn’t seem to make any difference. It just, it was. That’s all. . . . The houses didn’t burn, they exploded. The heat was so terrible that they exploded.”

South Waterboro, Shapleigh, Lyman, parts of Alfred would suffer a similar fate on Oct. 23.

AN ARMY – AND NAVY – OF FIREFIGHTERS

All along the shifting fire lines, thousands of men from surrounding towns as well as college and high school students fought the blaze or helped others escape.

Bates student volunteers who helped to fight the ’47 fires. Photo courtesy of Edmund S. Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library at Bates College

Richard Neal, the 16-year-old from Sanford, remembers deciding with two of his classmates to skip school and hitchhike to Waterboro to fight fires. He doesn’t even recall asking his mother’s permission.

The teens were given so-called “Indian pumps” – metal cannisters of water with backpack straps and a single hand pump – and were spread out along the fire line. They slept in barns, ate donated food and headed wherever they were directed.

At one point, Neal and his classmates encountered a state police trooper on Route 202 in Waterboro as the flames closed in. The trooper was about to lead them to a mill pond that would (hopefully) shield the group from the intense heat. But then the officer stopped an approaching driver and told her to take the boys and go, quickly.

“As we drove down (Route 202), all of the houses on the right side of the road were on fire and the flames were leaping across the road,” Neal, now 86, recounted recently. “The lawns and the houses on the left side of the road were catching on fire. And my friend said, ‘Lady, just follow the taillights of that logging truck.’ ”

Firefighters from New Hampshire and Massachusetts, as well as equipment, arrived in Maine. The military still had multiple facilities in Maine just two years after the end of World War II, so thousands of service members joined the firefighting, provided medical care, established communications lines or protected burnt-over areas against looters.

In a Nov. 14 letter to the Navy’s commander in Boston, Hollis selectmen expressed “their sincerest appreciation” for the men of the cruiser USS Little Rock for their “great help in diverting the fire around small villages.”

“In fact, without this cooperation and equipment, working in conjunction with the fire departments of surrounding cities and towns, it is doubtful if some of them would have been saved,” reads the letter.

Even so, the fires scorched more land in York County than in all other Maine counties combined – roughly 130,000 acres out of the 205,000 statewide that year.

FROM RICHES TO ASHES

The county with the largest financial loss – $5.8 million back then, or the equivalent of in 2017 dollars – was Hancock County, largely because of the destruction around Bar Harbor.

The fires that burned more than 10,000 acres in Acadia National Park roared down the slopes of Cadillac Mountain and surrounding peaks into Bar Harbor on Oct. 23. Dozens of mansions burned along “Millionaire’s Row” – today’s Route 3 between Bar Harbor and Hull’s Cove – along with Jackson Lab and many other homes or businesses on the outskirts of town.

Publisher Joseph Pulitzer, right, and his pilot, unidentified, view the remains of the estate of Mrs. William S. Moore, his sister inBar Harbor on Oct. 24, the day after the home “Woodlands” was burned to the ground. Associated Press

Thousands of residents were trapped on Bar Harbor’s downtown pier awaiting a water rescue before bulldozers were able to clear a last-minute path through the still-burning debris on Route 3. The flames crept to the very edge of the downtown business district, destroying three large hotels.

Unlike many rural towns in southern and western Maine, Bar Harbor would be rebuilt and would rebound. In fact, the 1947 fires marked “the end of an era” in Bar Harbor, Butler said in an interview, as the town shifted further away from a playground for mansion-owning wealthy families to the tourist town that it is today.

CATALYST FOR CHANGE

It would be six more days – and thousands more acres burned – before rain finally fell on Oct. 29. The fires on Mount Desert Island wouldn’t be declared entirely under control until mid-November.

Writing his official summary for the 1947-48 Biennial Report of the Commissioner, deputy forest commissioner Austin Wilkins described losses of buildings, lumber and standing forests as “the greatest this state has suffered since records have been kept.”

Putting the 205,678 acres of scorched earth in more understandable terms, Wilkins compared the burned area to “a strip 286 miles long and 1 1/8 miles wide, extending from Fort Kent to Kittery.”

Lessons soon emerged from the conflagration, however.

Towns with understaffed fire departments or antiquated equipment sought and often received funding to expand and upgrade. Other municipalities without volunteer fire departments, meanwhile, got busy forming them.

Fire fighting equipment in 1947: A pile of shovels and brooms for firefighters at the American Red Cross headquarters on State St. in Portland. Courtesy of the Brick Store Museum, Kennebunk, Maine

During the latter stages of the fires, Gov. Horace Hildreth had declared a state of emergency and consolidated all oversight of fire control in Augusta. The Maine Forest Service retained that oversight after the ’47 fires, taking a more active role in coordinating efforts to fight forest fires in towns and helping bear more of the costs.

“Fire prevention” also became a major component of state and local firefighting programs. And many of the state laws regarding permits for open burning or brush burning were put in place in the decade after the massive forest fires.

SCARS SOFTENED BY TIME

The communities ravaged by wildfires would inevitably rebuild, although some would fare better than others.

In just two hours, Newfield lost more than 40 houses, schools, a post office, at least one church and a mill.

“Many people lost all that they had worked their entire lives to build,” reads a historical account on the town of Newfield’s website. “Some moved on to begin again elsewhere, others rebuilt. But Newfield would never be the same.”

Other communities were transformed by the destruction.

Today, Kennebunkport’s Goose Rocks Beach is lined with more modern waterfront houses, some commanding seven-figure prices. In Bar Harbor, hotels replaced many of the mansions along “Millionaire’s Row,” hastening the resort town’s transition from the exclusive playground of families like the Rockefellers and Vanderbilts to a more egalitarian tourist destination.

The following spring, areas blackened by fire turned green as the forests began to regrow, albeit oftentimes with a different mix of hardwood trees than the firs that burned. And even today, it’s possible to distinguish between areas that burned from those that somehow escaped the erratic flames.

Caron, the Lyman resident who fled with her mother down smoke-choked roads, still resides on part of the farm her father owned in 1947.

“I live among the pine trees that survived,” Caron said. “I do have some very large pine trees.”

____________________________

CORRECTION: This story was updated at 8 p.m. on Oct. 23, 2017, to correct the spelling of Sheila Meek and her affiliation with the Kennebunkport Historical Society.

Send questions/comments to the editors.