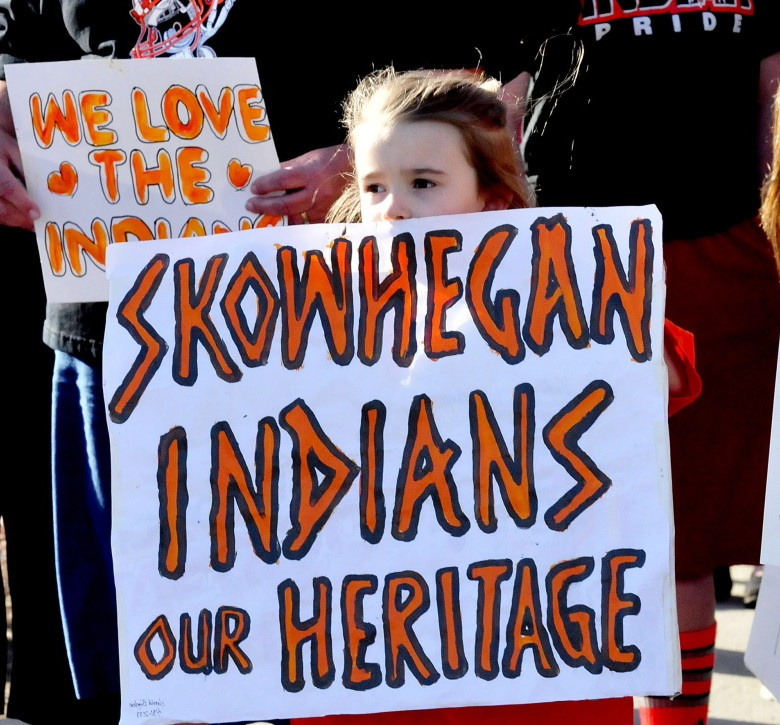

SKOWHEGAN — The continuing debate over the use of Native American images and nicknames for school sports teams is not about a handful of complainers seeking their 15 minutes in the spotlight, opponents say.

It’s about people and respect for a race which was nearly wiped out with the arrival of white European settlers.

And it’s not just a local issue in Skowhegan-based School Administrative District 54 where the school board voted in 2015 to keep the “Indians” nickname for its sports teams, despite opposition from the four Maine Native American tribes.

The tradition of the Skowhegan Indian on the field and on the court remains in place with no immediate plans for change, local school officials said Friday. This comes amid controversy of a Skowhegan Area Chamber of Commerce announced a holiday promotion called “Hunt for the Indian,” in which a small replica of the town’s iconic Skowhegan Indian sculpture by artist Bernard Langlais was to be placed in stores for shoppers to find for discounts and prizes. The chamber canceled the promotion after backlash on social media.

“No — not a chance,” SAD 54 school board member Harold Bigelow of Skowhegan, one of the district’s loudest supporters of “Skowhegan Indian Pride,” said of any possibility of a new vote on the issue. “We’ve already discussed this. With the taxes the way they are and everything — I’ve got a feeling — no. Why would you want to?”

Supporters of keeping the “Indians” name say the practice honors the strength and prowess of the people who first settled along the Kennebec River, which runs through Skowhegan. Opponents say Native Americans are not honored by being used as a mascot and that it is an insult to their culture and the real heritage of the region.

Representatives of the Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Maliseet and Mi’kmaq tribes — all members of the umbrella Wabanaki federation in Maine — told a school board subcommittee in 2015 that the use of the word “Indians” is an insult to them. Members of the four tribes, as well as the Bangor NAACP and others in the state, want the name changed, saying the tribes are people and people are not mascots.

SAD 54 Superintendent Brent Colbry said Friday that the school board has not scheduled another vote on the “Indians” question, but the public can request that the board revisit the issue.

“The board has not discussed it — we’re still operating within the same guidelines that were set after that last vote, which is that the only image that there is is that one that’s in the gym. That’s the only image that we endorse. We’ve had no further discussion since then; there’s no directive to do that.”

Nor is the mascot just a local issue at Wells High School where one Mi’kmaq mother said players mocked Native Americans with offensive stereotypes at a recent football game. Wells fans — both students and adults — were “running around with hands over their mouths,” making whooping sounds and banging on drums and 5-gallon buckets while making offensive chants, said Amelia Tuplin, whose 16-year-old son, Lucas Francis, is quarterback for rival Lisbon High School.

Some fans had painted their faces with “war paint,” she said. At the end of the game, the Wells football team gathered and did what Tuplin termed “a mock dance, putting their helmets up and down, and doing a mock chant.”

The school committee said it will review the Wells High School mascot and logo and plan to conduct a community forum on the issue.

For the past 40 years the negative stereotypes of Native people has become a national debate, from use of the names Redskins and Braves to “tomahawk chops” and the grinning cartoonish Chief Wahoo, the Cleveland Indians mascot.

As recently as this past Thursday, people at Keller High School in Texas said they wanted their school mascot to be changed from “Indians” to something less offensive. But parents and alumni are pushing back.

Those trying to keep the mascot say it’s part of Keller tradition, meant to honor the area’s Native American history, as some Skowhegan residents say.

Keller resident Yolanda Blue Horse said she was offended.

“Our dress, our regalia, the way our ancestors dressed is very sacred to us, very sacred,” Blue Horse said. “If I feel this way, if I feel hurt, if I feel misrepresented, if I know that this is not the way I was raised of who my people are, how does a child feel, who is in the years of self-identity?”

Skowhegan school board member and former selectwoman and county commissioner Lynda Quinn said she doesn’t see any reason to vote again on the nickname and added that she takes issue with the use of the word “mascot” to describe the Skowhegan Indians.

“We got rid of that mascot in 1990,” Quinn said. “We all agreed that the little running Indians were a caricature, were insensitive and it wasn’t right. That was when we painted all that stuff out from the cafeteria, from the gymnasium, on the football field — we took care of all those caricatures. We retired the costume that somebody used at games. The only logo the high school has now is the Indian on the river bank spearing fish, which kind of goes with Skowhegan.”

As for the teams’ nickname, is there a chance for another vote?

“From my perspective, no, I don’t think so — I think that was put to rest,” Quinn said. “My question is I don’t know what’s wrong with the name ‘Indian’. It’s not making fun of anyone. It’s not disrespectful. I just don’t understand why they’re so opposed to the name ‘Indian.'”

But others, locally and nationally, disagree and say the name “Indians” should be retired.

Rather than honoring Native people, the caricatures and stereotypes are harmful, perpetuate negative stereotypes of America’s first peoples and contribute to a disregard for the humanity of Native peoples, said Brian Cladoosby, president of the National Congress of American Indians in an April 2014 opinion editorial in the Washington Post.

“The invisibility of native peoples and lack of positive images of native cultures may not register as a problem for many Americans, but it poses a significant challenge for native youth who want to maintain a foundation in their culture and language,” Cladoosby wrote. “The Washington team’s brand — a name derived from historical terms for hunting native peoples — is a central component to this challenge.”

The matter of “hunting native peoples” came rushing to the forefront this month when the Skowhegan Area Chamber of Commerce announced a holiday promotion called “Hunt for the Indian,” in which a small replica of the town’s iconic Skowhegan Indian sculpture by artist Bernard Langlais was to be placed in stores for shoppers to find for discounts and prizes.

The ensuing social media storm objecting to the promotion forced the chamber to withdraw the promotion, suspend sales of the wooden replicas and promise a community forum on the issue, but the hurt — and the memory — was real, said Maulian Dana, a Penobscot woman from Indian Island and the local founder of the “Not Your Mascot” group.

Dana said tribal members are taught about the massacre of their ancestors at the Norridgewock village of Old Point in what is now Madison in 1724. Survivors of the attack by British soldiers fled north to Canada and to Indian Island where some of Dana’s ancestors settled.

Thirty-one years later, in 1755, Spencer Phips, lieutenant governor of the Province of Massachusetts, of which the District of Maine was a part, issued a proclamation inviting white settlers to “embrace all opportunities” to pursue and kill Penobscot people in Maine. The proclamation promised a bounty to be paid for living Indians and for the scalps of dead ones — men, women and children.

The Phips Proclamation contributed to the annihilation of the Wabanaki Confederacy which included between 16 and 30 tribes. Only four tribes remain today in Maine — the Penobscot, the Maliseet, the Passamaquoddy, and the Mi’kmaq.

Dana said the Chamber’s failed holiday promotion could lead to new talks about changing the Skowhegan “Indians” nickname.

“It definitely strikes a chord because of the (Phips) proclamation, being that it was written to hunt Penobscots and most of us know about it — we learned about it growing up and read the different amounts for the bounties on men, women and children,” Dana said. “To read that — they want to hunt Indians — you can definitely feel the parallel, whether it was intentional or not; it’s sad we have to even feel that way and be reminded of that traumatic past.”

She said the link between the Chamber’s promotion and the continued use of the “Indians” nickname can not be ignored.

“I think that it is absolutely a perfect time to change the mascot,” Dana said. “I think a lot of people in the community are really motivated to make this change and do the right thing. Social change is never comfortable. People are going to have no choice but to look deeper into the mascot issue at the high school.”

Doug Harlow — 612-2367

Twitter:@Doug_Harlow

Send questions/comments to the editors.