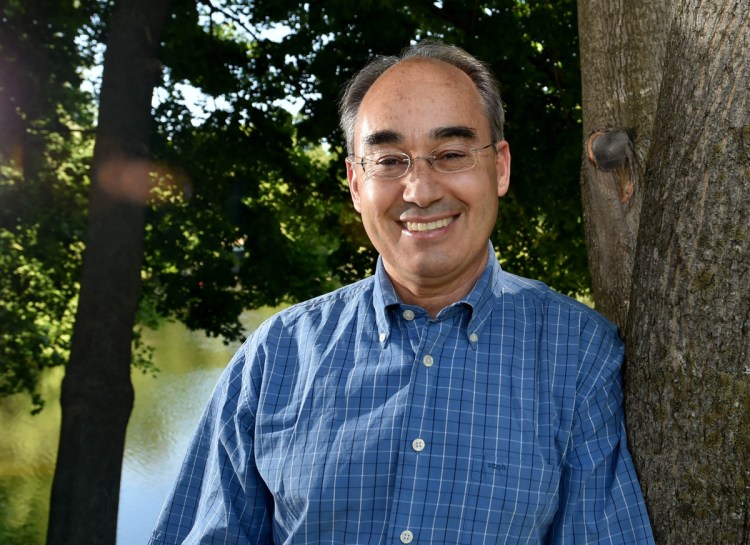

On the first Friday of February, U.S. Rep. Bruce Poliquin was feeling generous.

Despite facing a potentially hot re-election contest that might force his campaign to shell out millions of dollars on television advertising, consultants and all of the accoutrements of a modern-day political showdown, Poliquin opted to dip into his coffers for something entirely different.

Poliquin gave away $8,000 that day, spreading it evenly among charities from Auburn to Caribou.

Listed in the final pages of a long quarterly finance report he filed with the Federal Election Commission are details of both his giving and his overall spending.

Poliquin forked over $1,000 to the Pine Tree Society, a longtime nonprofit that aims to transform the lives of Mainers with disabilities and their families.

He handed over similar checks to Martha & Mary’s Kitchen in Presque Isle, Honor Flight Maine in Portland, Arise Addiction Recovery in Machias, House in the Woods in Lee, Allen’s Way in Caribou, The Bangor Area Homeless Shelter and the Aroostook County Action Program.

Brent Littlefield, a Poliquin consultant, said the congressman “chose to donate a total contribution amount previously received from one source. He didn’t ask for media attribution for doing it; he just wanted to do it because he felt it was the right thing to do.”

It’s the only time in the past year that Poliquin donated any campaign money to charity, a move that is unusual in political circles.

Its timing is interesting.

That same day — Feb. 2 — the Sun Journal published a story online about the surging social media campaign of a lawyer planning to take on Poliquin in the general election. Tiffany Bond, an independent, told supporters she didn’t want their campaign donations. She urged them to give the money instead to charity or to buy something from a small business in Maine.

“I hope my campaign is contagious,” Bond said upon learning of Poliquin’s giveaway. “I’m honored Bruce followed my example and commend him for making this kind choice.

“Anyone running for office, particularly incumbents, should be working each day to improve the lives of constituents. It’s public service, not self-service,” she said.

Politicians sometimes give campaign cash to nonprofits, but it is uncommon, especially among those actively running for re-election in races that could be tight.

The Federal Election Commission says that campaign committees “can give gifts to charity” but warns that “the amount donated to a charitable organization cannot be used for purposes that personally benefit the candidate.”

Typically, though, campaign cash doesn’t wind up in the hands of a charity unless the politician who raised it is bowing out of the public arena.

Former U.S. Sen. Joe Lieberman of Connecticut, for example, used his leftover campaign cash after his retirement five years ago to create a scholarship fund. He also used some of it to organize his personal papers before giving them to the Library of Congress.

Candidates are much more likely to use an excess or leftover campaign money to help other politicians. They can give it to other campaign committees or political parties.

Poliquin occasionally dips into his campaign cash to lend a hand to Republicans running for U.S. House seats. They, in turn, sometimes donate to him.

Most of the spending that Poliquin has done during the first quarter of the year is pretty typical for a member of Congress seeking re-election.

Between Jan. 1 and March 31, Poliquin shelled out $24,330 to Gula Graham, a fundraising consultant in Washington, D.C., that touts its expertise in helping incumbents find money for their races.

Campaign consultants also pocketed quite a bit: $12,102 to Littlefield Consulting in Washington, $6,000 to the Massachusetts-based SCR & Associates, $6,000 to Lee Jackson in Old Town and $3,000 to Hutson Consulting in Oklahoma.

Poliquin paid $7,200 to Aristotle International for database work, $5,542 to Same Day Processing in Minnesota for compliance consulting, $1,023 to Facebook for online advertisements and $1,425 for airline and train travel,

Poliquin’s campaign also forked over $1,476 to the Capitol Hill Club in Washington for food and beverages and $1,500 to Twenty First Century Group to rent event rooms in the nation’s capital.

Poliquin dropped $3,164 to the Apple Store in January and exactly the same amount the same day for Hutson Consulting to get office equipment.

In addition, Poliquin himself got $2,909.22 for “in-kind lodging.” He also repaid $50,000 toward a $200,000 loan he gave his campaign committee in 2014, most of which he has yet to get back.

Poliquin has more than $2.2 million in his campaign coffers, more than three times the amount that his four Democratic backers have squirreled away combined.

Send questions/comments to the editors.