Muslim immigrants who have already arrived say it will speak to whether they are really welcome.

Mehdi Ostadhassan is a celebrated professor and scientist, a mentor, a husband and father, and he has been a North Dakotan for the past nine years.

He is also a Muslim and an Iranian national – a citizen of one of several majority-Muslim countries targeted by President Trump’s entry ban. And despite having a résumé that seems to match the Trump administration’s preference for a “merit-based immigration system,” he is now in his fourth year of an increasingly desperate quest for U.S. citizenship.

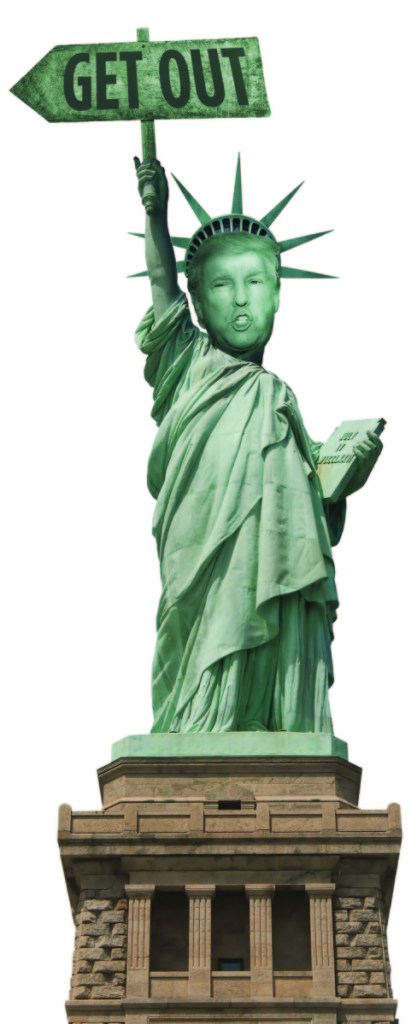

Ostadhassan’s immigration woes have nothing to do with Trump’s entry ban, which went into effect last December and which the Supreme Court recently began evaluating. But he believes his trouble has everything to do with his being a Muslim. For that reason, Ostadhassan will be waiting, along with millions of others inside and outside the United States, to see what the court decides.

He believes the decision has the potential to influence the fortunes not only of those hoping to migrate to the United States but also of those Muslim immigrants already living here. Many fear that a Supreme Court decision upholding the ban would send a powerful negative message about the place of Muslims in the United States.

“People will feel like they’re not welcome in a country that’s supposed to provide all these opportunities and all this freedom, and I think that’s sad,” said Mahsa Payesteh, outreach coordinator for the National Iranian American Council.

The Supreme Court last Wednesday heard arguments in the case of Hawaii v. Trump, examining how far the president’s authority extends in determining U.S. immigration policy. At issue is Trump’s September proclamation that banned entry to the United States for citizens of five majority-Muslim countries as well as North Koreans and certain Venezuelan government officials, with limited exceptions.

The order was the third iteration of Trump’s original entry ban, which applied to citizens of seven majority-Muslim countries. Trump has argued that the ban is necessary to protect national security.

The case also will determine whether the president violated the Constitution or the Immigration and Nationality Act by discriminating on the basis of religion or nationality.

The justices are expected to issue a ruling in June.

An estimated 3.4 million Muslims live in the United States, accounting for dozens of nationalities and ethnic heritages. Some, like Ostadhassan, hail from countries covered by Trump’s ban – Iran, Libya, Somalia, Syria and Yemen – while others immigrated from Pakistan, Indonesia, Lebanon, Turkey and beyond.

But regardless of their citizenship status or national origin, many will be interested in the Supreme Court’s decision. To members of one of the United States’ least popular religious minorities, this will be more than a ruling on the president’s authority. It will be a culturally pivotal moment; a statement of the nation’s values.

Since its implementation in December, the ban has made “many members of my community feel like they’re second-class citizens,” said Debbie Almontaser, a board member of the Yemeni American Merchants Association in New York who knows American Muslims across the country, including two of her nephews and one niece, who have Yemeni spouses stranded abroad. “Like, you’re American, but we’re not going to let you have that American Dream,” she said.

Since Trump was campaigning for the presidency, his comments about Muslims – tying immigrants to the Islamic State and as president retweeting anti-Muslim propaganda videos and appointing advisers and Cabinet secretaries who have characterized Islam as dangerous – have harmed their American experience, many say.

FBI data showed a precipitous rise in reported anti-Muslim assaults during the election year. In 2017, nearly 1 in 5 Muslims in the United States said that racist or otherwise offensive language had been directed at them.

“Trump’s xenophobic rhetoric, both prior to and during the course of his presidency, emboldened those who sought to express their anti-Muslim bias and provided a veneer of legitimacy to bigotry,” the Council on American-Islamic Relations said in a report released last Monday.

A high courtourt decision affirming the entry ban would, some fear, perpetuate that trend.

“It’s huge for Muslims,” said Faiza Patel, co-director of the Liberty and National Security Program at New York University School of Law’s Brennan Center for Justice. The president’s words and policies have “really shaken their faith in what America really stands for.”

When Ostadhassan arrived in the Midwest from Iran nine years ago, the United States offered an opportunity for him to earn a doctorate in petroleum engineering and presented myriad other academic possibilities.

In the years since, Ostadhassan, 34, got married and had a child. Most recently, he developed an idea for a new method of cancer research using technology that he had previously used to analyze shale, and he won the support of the university’s medical school in the project.

Then, near the end of 2017 and after a yearslong wait, the U.S. government told him that his application for permanent-resident status had been denied.

“This is basically the end of my professional career,” he said, after the university was compelled to terminate his employment.

Ostadhassan is one of several people named in a class-action suit filed last year by the American Civil Liberties Union, before his residency application was denied.

While the lawsuit will not directly be affected by the Supreme Court decision on the entry ban – it focuses on a secretive Obama-era system called the Controlled Application Review and Resolution Program – it invokes Trump’s entry ban, outlining what it asserts are Trump’s comments and policies toward Islam and Muslims.

The lawsuit alleges religious discrimination against Muslims in the U.S. immigration system, and it argues that CARRP singles out and delays the applications of Muslims on the basis of religious affiliation rather than national security concerns.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services said it cannot comment on CARRP “due to pending litigation.”

But the broader implication, for many Muslim across the country, is that the Supreme Court’s decision on the entry ban will send a message about all kinds of religious discrimination, including existing government programs, that activists say target Muslims.

Even if the Supreme Court rules against the entry ban, Ostadhassan is still to have months or years of waiting and potential court battles ahead of him.

And if the court upholds the ban, he will have far less reason to be optimistic.

“It is one hundred percent a Muslim ban,” he said.

— The Washington Post

Send questions/comments to the editors.