Kevin Battle was a baby when church officials raided his family home in Ireland and plucked him from the arms of his mother, an unmarried 24-year-old who had run away from the convent where she and hundreds of other Irish girls were sent to give birth to secret children.

After raising the boy she named William for more than a year, his mother couldn’t bear to give him up, so she grabbed her chubby-cheeked boy and escaped home to her family in County Limerick. But the nuns had plans for the boy, so they tracked down the mother and child and forcefully reclaimed him.

Within weeks of seizing the baby, the Catholic Church sold him to an Irish couple in New York grieving the death of their own infant. The price? A $1,000 donation to the church. Records show that the convent, Sean Ross Abbey, secretly exported 438 children like Battle to America.

Yet Battle, a retired South Portland police officer who works as a harbor master and state legislator, grew up knowing none of this. He’d always known he was adopted. He’d searched for his mother, following the paper trail to Ireland in 1978, but the nuns there told him she was dead.

This is a photograph that Kevin Battle took of his birth mother, Catherine Sheehy Finnegan, from a video that his half-siblings played for him during a recent trip to meet his long-lost family in Wales.

“I thought I was an orphan, that she hadn’t wanted me and I’d never know why, but they lied,” he said. “She did want me. The church stole me from her, like they did to a lot of unwed mothers, and sold me. And years later, when I came asking, they lied and slammed the door in my face.”

It was a DNA kit that his wife gave him for Christmas that revealed a living first cousin one month ago. After decades of searching, Battle, who is 59, is finally learning the long-buried secrets of that dramatic beginning. He traveled to Wales this month to learn the rest of the story.

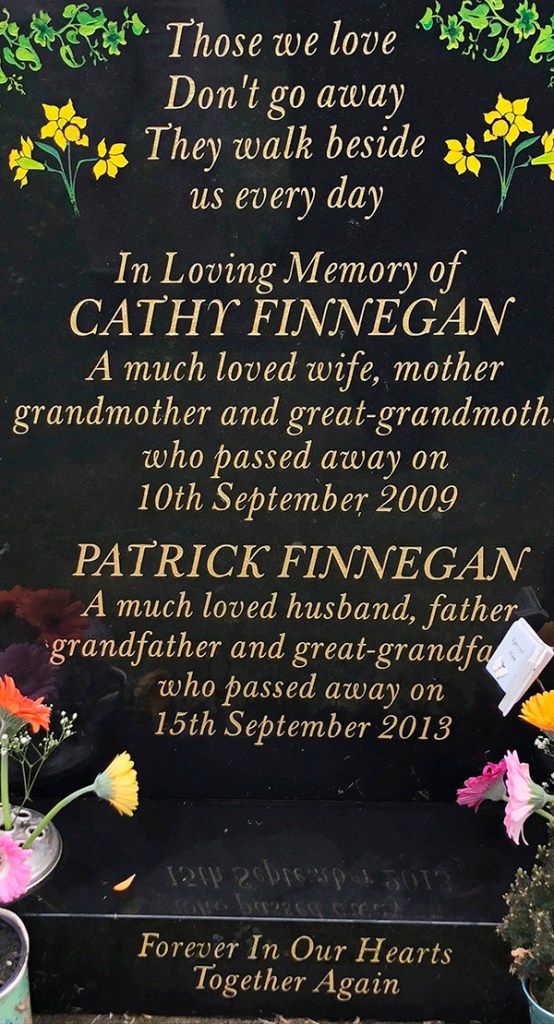

He met four of his five half brothers and sisters, sat in his mother’s favorite spot in her favorite pub and visited her grave. He cried when he counted six yellow flowers carved on her gravestone, one for each of her children – including him. His mother had not seen him in 57 years, but she had not forgotten him.

In the faces of his birth family, Battle found a familiarity that had eluded him. The similarity of the eyes, the beefy build, the quick, broad smile. He toured one brother’s job sites, ate dinner with a cousin, and pored over family photos with his sisters Tina and Tonya. He immersed himself in their everyday lives.

This is the only known photograph that shows Catherine Sheehy with her son, whom she named William. The child was forcibly taken from her by nuns from a now-infamous convent in Ireland.

“Maybe this is the closure I need,” he said. “I get into things, I join things, but I never truly feel like I am part of it. I always feel like I’m on the fringe, left out. Even being a cop, a fireman. Yeah, I’m there, but I’m not. Maybe that’s part of my not having my own family roots. Maybe this will change a little of that.”

•••••

Kevin J. Battle was born William Sheehy in July 1958 in Sean Ross Abbey in Roscrea, one of several mother-and-baby homes run by the Sacred Heart Sisters. Babies born to unwed Irish girls there were adopted out across Ireland, Germany, England and the United States from 1930 to 1970.

The practice of forcing unmarried pregnant girls into these convents, where they would toil in kitchens, gardens and laundries for three years to atone for their sins while nuns sold their children to unwitting couples, was revealed by a United Kingdom journalist in 2009 and turned into the 2013 film “Philomena.”

In 2014, after the Irish government announced it would investigate these mother-and-baby homes, the Catholic Church of Ireland apologized for its role in the forced adoptions and the hurt it had caused the unwed mothers who had lived and worked there and their children.

“We are reminded of a time when unmarried mothers were often judged, stigmatised and rejected by society, including the church,” the apology read. “The culture of isolation and social ostracizing was harsh and unforgiving.”

The Maine Irish Heritage Center in Portland, which has a genealogy division that helps Mainers trace their Irish lineage, had worked with other adoptees but never a Sean Ross Abbey baby, said Deb Sullivan Gellerson, a volunteer genealogist. Unfortunately, falsified records are common, she said.

Sometimes the girls or their families used fake names, while other times the nuns would falsify records themselves, so the public shame of giving birth out of wedlock wouldn’t follow them through their lives, she said. Unwed mothers were hidden, forced to give up their children and told to forget.

Kevin Battle, middle, enjoys a pint with his half brothers, Tony, left, and Bernie Finnegan, at a pub in Wales 2 weeks ago. Taken from his unwed mother as a baby by the Catholic Church of Ireland and sold to a New York family, Battle did not know his birth family until he took a DNA test this year. Here, he is sitting in the spot where his birth mother used to sit; she died in 2009.

Like Battle’s mother, many of the unwed mothers took their secrets to the grave, Gellerson said.

“These young women became pregnant out of wedlock and due to the families being ‘strict Catholics’ they had to send them away to give birth,” she said. “Then, the very same religious order abuses, sells or even killed these children, yet these abbeys and orphanages continued to operate for generations.”

•••••

Battle has no memory of his infancy in Ireland. He was shocked to learn he was one of those “stolen” Sean Ross Abbey babies. His earliest memory is walking up the steps to an upper-story apartment in Long Island, New York, to meet his adopted parents for the first time. He was 2 years old.

“The door opened up, and there were these two people I would come to know as my mother and father standing in the apartment,” Battle recalls. “I remember they gave me a ball, a red ball. I don’t know that I’d ever had a ball before. I ran inside to play with it. That’s it. My first memory.”

Battle still has that ball. For years, it sat on a shelf in his bedroom, emblazoned with his adopted name and the date of his adoption: Dec. 6, 1960. It represented the beginning of what he can recall. He has no memory of his birth mother, of their dramatic runaway attempt, or his trip to America.

The gravestone of Catherine Finnegan, birth mother of Kevin Battle, a retired South Portland police officer, state lawmaker and harbor master. Despite his efforts to find her, Finnegan died in 2009, eight years before Battle learned her identity and traveled to Wales to meet his half-siblings. Note the yellow flowers on the stone – one for each of her children, including Kevin, who she had not seen in 57 years. (Photo courtesy of Kevin Battle)

He grew up in Long Island and New Jersey. He had a happy childhood. He loved his mother, who stayed at home to raise him and a younger sister. His father was a pugnacious cabinetmaker with a quick temper who struggled with alcoholism, but he loved Battle in his own way. Both are now dead.

They didn’t know how their son had come to live in the orphanage. His father said he didn’t think it was right that he’d had to make such a big donation to the church to adopt the baby (that was in addition to regular adoption fees) but never suspected the church of human trafficking, Battle recalls.

Battle started digging into his past in high school when the local volunteer fire department told him he couldn’t join their ranks because his identification papers were incomplete. He wasn’t a U.S. citizen. He took steps to become naturalized and became a firefighter, but the experience shook him.

He tracked down his New York City birth certificate and eventually papers that showed he was born at Sean Ross Abbey in Roscrea in County Tipperary. His birth mother was listed as Kathleen Sheedy. It didn’t list an exact birth date, only July through September 1958.

Through the years, Battle tried to track down Sheedy. He would use her name as an example when he taught other police officers how to use computer databases to track down people. None of the Sheedys that matched his time frame ever responded to his emailed queries.

Years later, Battle would learn the Sacred Heart Adoption Society had falsified his adoption papers and changed his birth mother’s name. She was Catherine Sheehy, not Kathleen Sheedy. Many adoptees of Sean Ross Abbey and their birth mothers have reported similar falsifications.

In 1978, Battle traveled with his adoptive mother and a friend to Ireland. He journeyed out to the abbey, hoping to persuade a kindly nun to dig up his records and tell him something about his mother. But the nun who answered the door ran the former resident off.

“I went up, knocked on the door, told the woman who answered who I was, that I’d come from America but that I’d been born there and could she tell me about my mother,” he recalled. “She told me, ‘You are not welcome here, go away,’ and slammed the door. I couldn’t believe it.”

He looked around the outside of the abbey but he couldn’t see much from the outside, so he left. Later, at the local pub, a barkeep would tell him the burned-out area he had seen behind the convent was the place where the nuns had burned the birth and adoption records.

“They have a lot of bonfires out there, a lot of fires,” he recalls the bartender telling him.

If the nuns had given him access to his records at that time, he’d have learned his birth mother’s name. In 1978, she was still alive. He might have been able to track her down in Wales, where the family had moved to escape the church, and been able to reconcile with her.

•••••

She had been looking for him, too. His half siblings told him they had learned about him in 2009, on the day they buried their mother. Their father told them their mother couldn’t bear to share her secret while alive, but had wanted him to tell them when she died in case he ever came looking for her.

He told them that they had looked for William together – even though unwed mothers were forbidden to search for their babies, having signed away all rights to them and been threatened with damnation if they did – but the church told Catherine her baby was dead, killed in a car accident in New York.

But Catherine had always nurtured a slim hope that William was alive and looking for her, he told them.

The news came as a surprise to the two sons and three daughters that Cathy had raised in Wales with her husband, Patrick Finnegan. Finnegan asked them if they wanted to try to find the half sibling, get a nosy Irish aunt to “have an ask-about,” but they decided it was best to leave it alone.

According to Tony Finnegan, the oldest of the five Finnegan children, the siblings figured that if he had wanted to find his birth mother and any half siblings, he would have already done so by then, and if he didn’t, or perhaps didn’t even know he was adopted, the knowledge could stir up trouble.

“I told my dad, ‘Well, Mum’s gone now, so it’s too late for them to give it a go, and it doesn’t really have anything to do with you, so let’s just leave it,’ and that’s what we did,” Finnegan recalled during a phone call from Wales. “We just figured he’d have found us if he’d wanted. We didn’t know about all the lies.”

His wife tells Finnegan that he must have known something about Ireland’s history of forced adoptions, and even known of Sean Ross Abbey, because they watched “Philomena” together, but Finnegan says that he doesn’t even remember seeing the film.

“My wife tells me I’ve seen it, but I can’t remember the story,” Finnegan said. “You watch films like that and you feel sorry for everybody in it, but you don’t think it has anything to do with you. It’s not real, but 10 years on, you learn it was real, that it happened to your family. That’s your life in that film.”

What they didn’t know was that Battle had already returned to Ireland, and had even traveled out to the rural convent listed on his birth certificate – at least the place of birth was accurate – trying to find even a shred of evidence that might lead him to the woman who had given him life.

A few years ago, after the stories of mistreatment within unwed mothers’ homes began to come out, the church sent Battle a letter offering to share his adoption and birth records with him, but it would cost him 100 English pounds. “Sure, I’ll pay you – you’ll give me more lies,” he thought with disgust.

The letter gave him a new name for his birth mother, a name that would turn out to be the real one. He called the abbey and asked to speak to the nun in charge of caring for the mothers and babies, and he eventually spoke to Sister Hildegarde McNulty. He asked for information about his mother.

“‘Oh yes, I remember your mother. She was tall and thin, training to be a nurse,’ ” he recalls her saying.

His police training told him she was lying, but he didn’t know how much of it was untrue. He would later learn from old family photographs he studied in Wales that his mother boasted a hardy build, one that suited her when she would earn money picking potatoes from a nearby farm.

McNulty told him that his birth mother had died. While he didn’t believe that either, he also worried that the church had gone to such great lengths to bury the histories of the adopted children – the lies, all of the missing records, falsified records – that he might never learn the truth.

That truth would come wrapped up in holiday paper as a Christmas gift from his wife. She had bought them both AncestryDNA kits. She was well aware of how hard her husband had worked to track down his family, and the dead ends and disappointments he had endured.

To his surprise, AncestryDNA tracked down a first cousin in Wales in March, a few days after his wife, also named Cathy, had learned she had cancer. He sent off an inquiry over the weekend while waiting for the doctors to call her with a recommended course of treatment.

While the doctors were hopeful, the cousin’s reply wasn’t as promising. It basically said, “I’m busy, but I’ll get back to you.” He figured that was the end of that. But a few days later, as he and his wife began preparing for her surgery, the cousin got back to him with the first good news.

“We’ve been looking for you,” began the email that would rewrite Battle’s life story.

•••••

The week after his wife began chemotherapy, during her first recovery week, Battle hopped on a plane to London. He considered postponing the trip to be with her, but she urged him to go then, before it got worse. She said she didn’t want him to miss a chance to meet his long-lost family.

Tony picked him up at the airport, worried that jet lag might cause Kevin to drive off the road on the long four-hour trip back to Wales. Both had worried about the initial meeting – Kevin joked it would “either be the fastest or slowest drive of my life” – but they quickly struck up an easy rapport.

“I was sort of apprehensive. After all, I grew up thinking I was the first of five and then I’m learning that’s not so, that I am the second of six, but after talking to him for a half-hour, I could tell he was a good guy, and I wasn’t really worried anymore,” Tony said. “He’ll always be welcome here.”

The emailed photos and video chats made it easy to recognize each other at the airport.

“When he came up to me, I said, ‘Hi, I’m your brother, Kevin,’ and I shook his hand,” Battle recalled. “It’s a thing I never thought I’d be able to say to somebody, let me tell you. For most people, it’s nothing, the thing you say without thinking, but I’ve never had that.”

Battle shared the details of his visit last week at the McDonald’s at Mill Creek in South Portland. He just shook his head, a delighted smile never leaving his face, as he cataloged the memories, spinning yarns about things as simple and sweet as souvenir shopping with a sister.

He talked about watching a video of his mother at a family wedding over and over again. She didn’t say anything that could be heard over the din of music and conversation, but the way she blushed and then batted her eyes at the camera told him she had a playful nature, just like him.

He visited her gravesite because “I had some things I wanted to tell her,” Battle said. He told her not to worry, that he’d turned out all right, that he’d served in the Coast Guard, the police force and as a state lawmaker. He said he would like to think she’d have been proud of him if they’d met.

The trip highlight was when a sister gave him a grainy black-and-white photo of his mother holding him. Having arrived in the U.S. as a toddler, he’d never had a baby picture. He’d always had to imagine that he was one of the nameless babies featured in eerie historic Sean Ross Abbey photos.

The blurry shot is hard evidence that his birth mother had loved him, he says.

“Look at how she’s holding me,” Battle said. “Look at her smile. She’s out of the convent, and she’s got me, and she’s happy. This must have been taken during the two or three weeks she was home with me before the nuns busted in and took me. She did want me, I see that now.”

Battle wants to return to the family homestead where this photo was taken as soon as his wife is feeling well enough to travel. He looks forward to Maine visits from his half siblings and to meeting a half sister, Bridie, who is currently living in Dubai.

He is hopeful that he might one day find his father, about which the Finnegan children know nothing.

“After so many years of bad information, dead ends, now it’s happening,” Battle said, flashing the same smile his mother had given the wedding photographer a decade ago. “I may finally get answers. It was not a happy beginning, that’s for sure, but it’s my story, and I want to know it.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.