Excessive force by police officers is a national problem, but the solution will need to come from state and local governments. The federal courts and federal government are showing themselves unwilling to deal with the problem, but meaningful action at the state and local levels is possible and, indeed, essential.

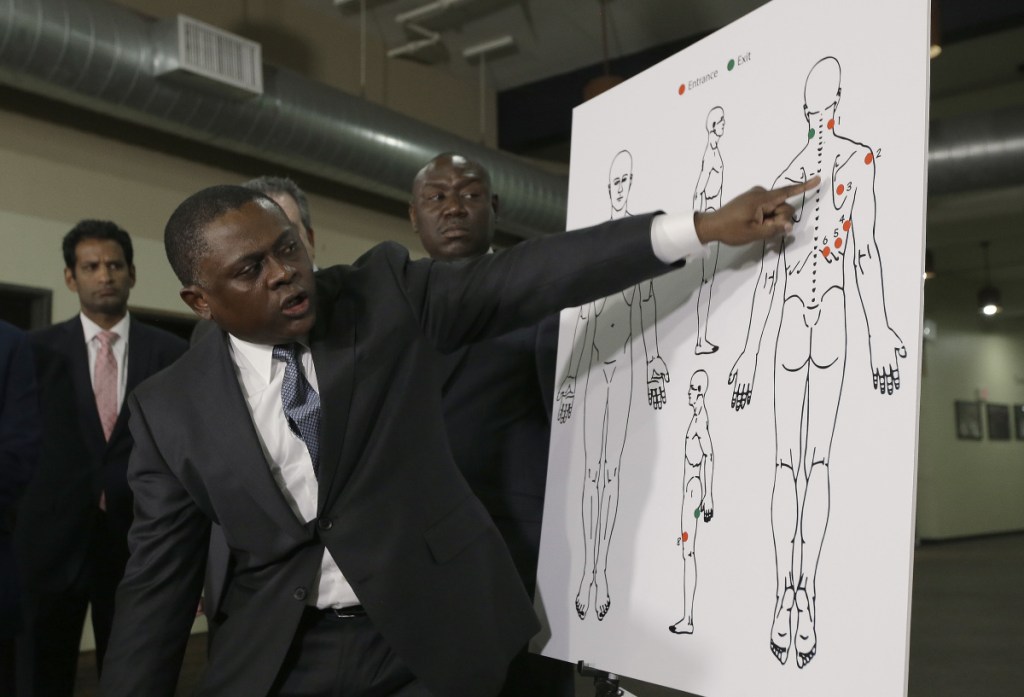

On March 18, Stephon Clark was killed by two Sacramento police officers who shot at him 20 times. The officers said they saw a gun, but all that was found near Clark’s body was a cellphone. Like Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Walter Scott, Laquan McDonald and Freddy Gray, Clark was an unarmed black man killed by police officers.

A federal statute authorizes the Department of Justice to bring lawsuits against police departments when there is a “pattern and practice” of civil rights violations, including excessive force by officers. This authority has been used to reform a number of major police departments, usually through negotiated settlements (known as consent decrees) with the cities.

Angelenos are familiar with a Justice Department action against the Los Angeles Police Department after the Rampart corruption scandal, which led to a consent decree that went into effect in 2001 and brought long overdue reforms that meaningfully changed policing in the city. But U.S. Atty. Gen. Jeff Sessions has made it clear that under his leadership, the Justice Department is not going to be using this authority.

At the same time, the Supreme Court has made it difficult for individuals to bring civil rights suits against police departments and police officers. Under Supreme Court precedent, a city can be held liable only if it is proved that the city has in place a policy that violates the Constitution.

And in case after case, the Supreme Court has found that police officers have immunity from suits for excessive force because, under present law, they are allowed to use lethal force when it is “reasonable,” a fairly lax standard.

Most recently, on April 2, in Kisela vs. Hughes, the Supreme Court held that a police officer in Tucson could not be sued when he shot and seriously wounded a woman. The officer was responding to a call that a woman with a knife was acting erratically. Rather than pursuing less lethal options, the officer began shooting the woman within a minute or two of arriving at the scene. This case is typical of many in which the court reversed lower court rulings that had found in favor of those injured or killed by police violence.

While successful civil suits are difficult, criminal prosecutions against police officers for excessive force are even less likely to succeed. Prosecutors generally are reluctant to bring such actions and when they do, juries for many reasons rarely convict, including because police are held blameless so long as they act reasonably.

But there is much that state and local governments can do to change the standard and to better deal with the problem of excessive force by the police. Legislation pending in California, Assembly Bill 931, would permit police to use deadly force only when it’s “necessary” to prevent imminent and serious bodily injury or death. That is, under this law, lethal force would be justified if, given the totality of the circumstances, there were no reasonable alternative, including warnings, verbal persuasion or other nonlethal methods of resolution or de-escalation.

Some cities have already moved, through administrative policy changes, to limit police use of force. Their experience shows that such reforms work. In New York, following a shift to minimum use-of-force policies, police went from shooting 994 people in 1972 to 79 people in 2014. The LAPD formally revised its use-of-force policy in 2017 to emphasize de-escalation; San Francisco introduced an even stricter policy in 2016. In 91 of the 100 largest U.S. police departments that were recently studied, jurisdictions with more restrictive use-of-force standards had the fewest officer-involved shootings per capita. Studies show that such policies are also associated with a decrease in the number of police officers killed in the line of duty.

AB 931 would change the criminal standard by which officers are judged throughout the state. It would force all departments to match their policies and training to a strict standard. Some police unions have indicated they will fight the change. San Francisco Dist. Atty. George Gascon has joined with civil rights groups to champion it. Gascon previously was the police chief in San Francisco and deputy police chief in Los Angeles.

My hope is that other prosecutors and police chiefs will join Gascon in advocating for the state law. Being a police officer is unquestionably a dangerous job that often requires split-second life-and-death decisions. But too many have died and been seriously injured from unnecessary police use of deadly force. Reforming the laws that set the standards is essential and California can lead the way.

Erwin Chemerinsky is dean and Jesse H. Choper distinguished professor of law at the UC Berkeley School of Law.

———

©2018 Los Angeles Times

Visit the Los Angeles Times at www.latimes.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Send questions/comments to the editors.