HANCOCK — When cruise ships anchor outside Bar Harbor, you can see them from most every dock and cove on Frenchman Bay, the great embayment on Mount Desert Island’s eastern flank, with Cadillac Mountain on one side, Acadia National Park’s Schoodic Peninsula unit on the other, and fishing hamlets, modest villages, and tasteful summer colonies in between.

Residents and cottage owners in these towns don’t see crowds of passengers and the money they spend, but on most summer and fall days they do have cruise ships in their front yards, some over a thousand feet long, 17 stories high, and nearly 10 times as massive as a World War II aircraft carrier, with exhaust plumes rising from their funnels.

But it’s what they might release into the bay that has Renata Moise and many of her neighbors around the bay worried.

“These are giant ships with thousands of passengers, and they can dump their treated sewage here which has tons of nitrogen in it, and that’s very concerning,” says Moise, a nurse midwife and co-founder of Friends of Frenchman Bay, a citizens group opposed to large-scale cruise tourism. “They’re changing the bay, and in my mind it’s killing the goose that lays the golden egg.”

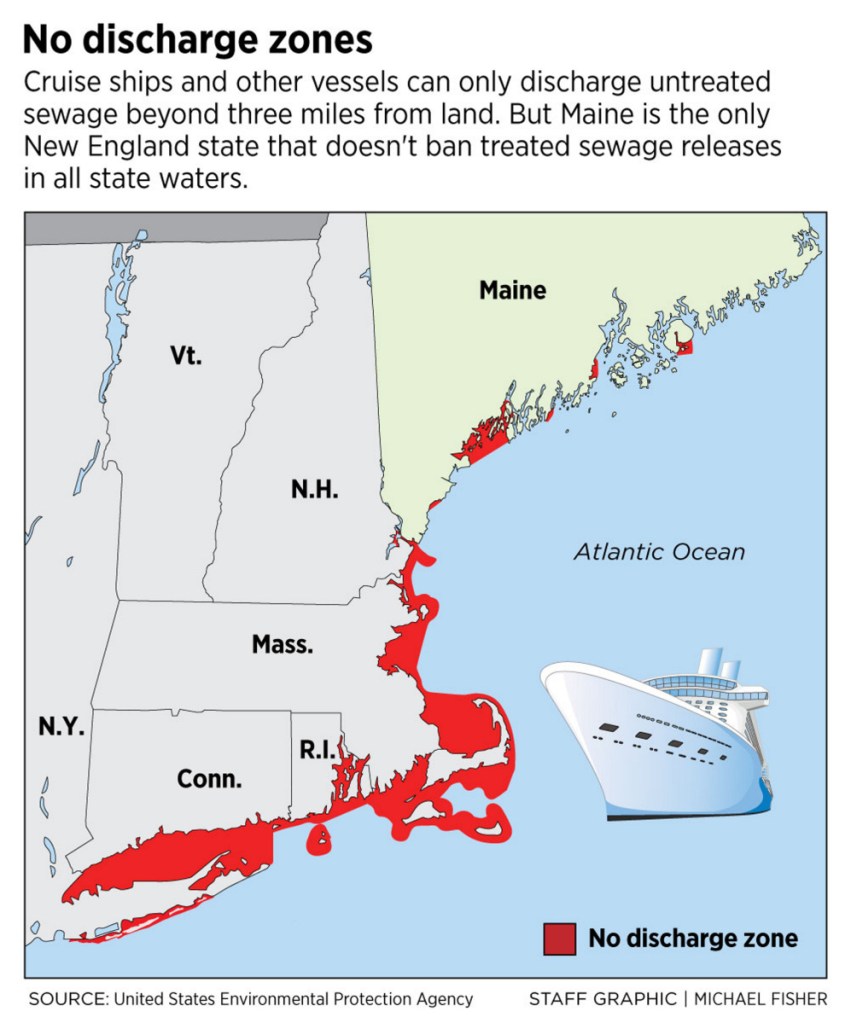

Cruise ships and other vessels are prohibited from releasing untreated sewage within 3 miles of land, but they’re allowed to pump out treated sewage in coastal waters that haven’t been declared “no discharge zones,” a federally assigned designation that has to be requested by state and local authorities.

Four of the five coastal New England states have secured such protection for their entire coasts, extending 3 miles from land or islands. Maine is the exception. Outside of Casco Bay there are just four small no-discharge zones in Maine: Boothbay Harbor; the Camden-Rockland area; the Kennebunks; and Somes Sound and the Cranberry Isles area southeast of Mount Desert.

The reason more of Maine isn’t protected is a shortage of wastewater pump-out stations at marinas and commercial docks, which recreational boaters, lobstermen, and the operators of other small vessels that rarely venture out of state waters need access to in order to comply, and which the federal government requires before approving new discharge zones.

“There was discussion in the past as to why we don’t just make the whole coast a no-discharge zone, but you really need the infrastructure in place first,” says Pam Parker, the state Department of Environmental Protection’s longtime water enforcement unit manager, whose office is pushing for a new zone between Wells and the New Hampshire border.

Frenchman Bay, where 148 cruise ships visited last year, has no such protection. Friends of Frenchman Bay have started the long process by educating communities about what it involves and advocating for more pump-out stations to be established.

Most large cruise ships have sewage treatment plants equal to or superior to those of Maine towns and cities, but the effluent is still loaded with nutrients, which trigger marine algae blooms that damage marine ecosystems and can result in the formation of “dead zones” with too little dissolved oxygen for fish and other marine animals to breathe. The larger cruise ships visiting Bar Harbor have more than 4,000 people aboard – more than many Maine towns – and Frenchman Bay often has two or three ships visiting at a time in peak season.

Cruise lines have pledged not to discharge in Maine waters, but their association has aggressively opposed the creation of no-discharge zones that would outlaw the practice. Critics distrust industry promises because Princess Cruise Lines, a division of Carnival Corp., was sentenced by a federal judge to pay $40 million in fines in April 2017 after pleading guilty to having intentionally discharged oily wastes via a “magic pipe” for years aboard one of its ships, and covered up other types of intentional, illegal discharges from four other ships. Carnival is under probation until 2022, with mandatory environmental audits of its ships, which account for dozens of port calls in Maine each year.

Cruise lines fought Casco Bay’s designation as a no-discharge area in 2006, sending lobbyists to Augusta to testify against it and even meeting with DEP staff behind closed doors in an attempt to create an exemption for cruise ships. The latter was squelched by then Gov. John Baldacci, when representatives from the nonprofit Friends of Casco Bay made him aware of the situation.

“It truly was a David-and-Goliath fight,” says Cathy Ramsdell, the nonprofit’s current executive director. “The cruise industry said they wouldn’t come here if we had that.”

Amy Powers, then director of CruiseMaine, the quasi-governmental entity that promotes Maine to the industry, warned legislators that a zone would “create an unfriendly sailing atmosphere” and “would be devastating from a marketability standpoint.”

Instead, cruise visits to Portland continued dramatic growth, in part because the city and state invested in a second cruise ship pier at the new Ocean Gateway terminal.

“We showed them you can have both,” recalls Baldacci, who supported both the zone and a bond issue that helped build the pier. “You can preserve and protect the natural resources and have a good and vibrant economy at the same time.”

The Cruise Lines International Association declined interview requests but said in a written statement that the industry had opposed the Casco Bay zone because it “added another layer of compliance when the industry was not discharging in state waters to begin with.”

Colin Woodard can be contacted at 791-6317 or at:

cwoodard@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.