The very first week that the iconic children’s television show, “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood,” aired, in 1968, the puppet character King Friday XIII built a wall. Yes, just the kind of wall we’ve all been hearing about for the past two years. A wall to keep people out.

The king doesn’t like change. He thinks the solution is to erect this barrier around his castle.

Eventually, King Friday sees the error of his ways — after balloons bearing messages of peace and love float his way.

Oh, how I wish that approach could help us in our current situation.

Well — I’m not exactly ruling it out.

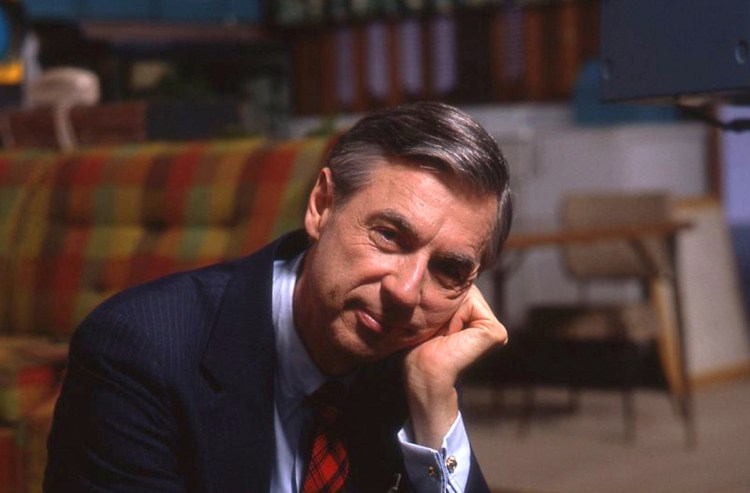

A documentary about Fred Rogers’ life and work, “Won’t You be My Neighbor?,” came out this year. I recently saw it at Railroad Square Cinema in Waterville. It is an inspiring film, but not just because of the message of acceptance Rogers delivered to children. He was, it turns out, a master of using goodness, kindness, love, to influence change.

That is surely something to think about in a time when the president of the United States is constantly tweeting about “Crooked Hillary” and “Cryin’ Chuck Schumer.” He portrays the media as the “enemy of the people,” composed of journalists who purvey “fake news.”

This language has created an ugly and divisive environment. Republicans who still possess a moral compass are dropping away from the party as a result. And that wall has not yet been built.

I try to remain hopeful that the forces of good will win, eventually. But this can’t happen by fighting fire with fire. Fred Rogers showed us another way.

In 1969, with the Vietnam War raging, President Richard M. Nixon needed money to fund it. He wanted to cut $20 million from the budget of the Public Broadcasting System, the network on which “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” aired. So Mister Rogers went to Washington to testify before the Senate Subcommittee on Communications.

Sen. John O. Pastore, Democrat of Rhode Island, was gruff and impatient. Rogers, however, remained his calm, patient and polite self. He asked if he could recite the words of a song from the show: “What do you do with the mad that you feel?” As an article in the Huffington Post noted, “Pastore, who had never seen Rogers’ show, was visibly touched by the speech.” Pastore said, “I’m supposed to be a pretty tough guy, and this is the first time I’ve had goosebumps in the last two days. Looks like you just earned the $20 million.”

Well played, Mister Rogers. Of course, he was just doing what he told America’s children to do: “Be yourself.”

Another seminal moment in the series came that same year, when Rogers invited Francois Clemmons, who depicted the neighborhood police officer, to share his pool. Clemmons is African-American. At the time, public pools had become a battleground in the civil rights movement. A clip in the film shows irate whites throwing water treatment chemicals into a pool to force blacks out.

Rogers’ reaction to this racism was to lead by example. He remarks that it’s a hot day, takes off his socks and shoes, and puts his feet into a wading pool. When Officer Clemmons pops by, Rogers urges him to do the same. He then offers Clemmons his towel to dry his feet when the policeman is ready to return to work.

Such a small gesture of kindness, and yet such a huge message.

The whole premise of “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood,” was, of course, that love, acceptance, and tolerance rule. The neighborhood is a microcosm of the global community. The puppet Daniel Striped Tiger (who was Rogers’ alter ego) asks Lady Aberlin if he is “a mistake,” a very personal question. But at another time, he has the sort of universal query that can be heard around the world: “What is assassination?”

Children were helped on a personal level when Rogers dealt with big questions like political assassinations and racism and such disasters as the explosion of the space shuttle Challenger. But he also suggested ways for them to think about such issues, as citizens. In the song “Teach Your Children,” Graham Nash wrote, “You, who are on the road/must have a code/that you can live by.”

That code has been torn asunder, which makes Fred Rogers’ message ever more important.

Abraham Lincoln, in his first inaugural speech (1861), lamented the split in the Union: “We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection.” He is sure that at some point, Americans will be “touched … by the better angels of our nature.” We were, eventually. The question of the moment is, can we raise those angels again?

Liz Soares welcomes email at lizzie621@icloud.com.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Related

J.P. Devine Movie Review: ‘Won’t You Be My Neighbor?’