Patrick Munzing said it with a slight smile. Like he couldn’t resist.

The Gardiner defensive coordinator was answering a question about when he played for the Tigers, and he made little effort to stop himself from including an extra detail.

“I played ’96, ’97, ’98,” he said. “And we never lost to Cony.”

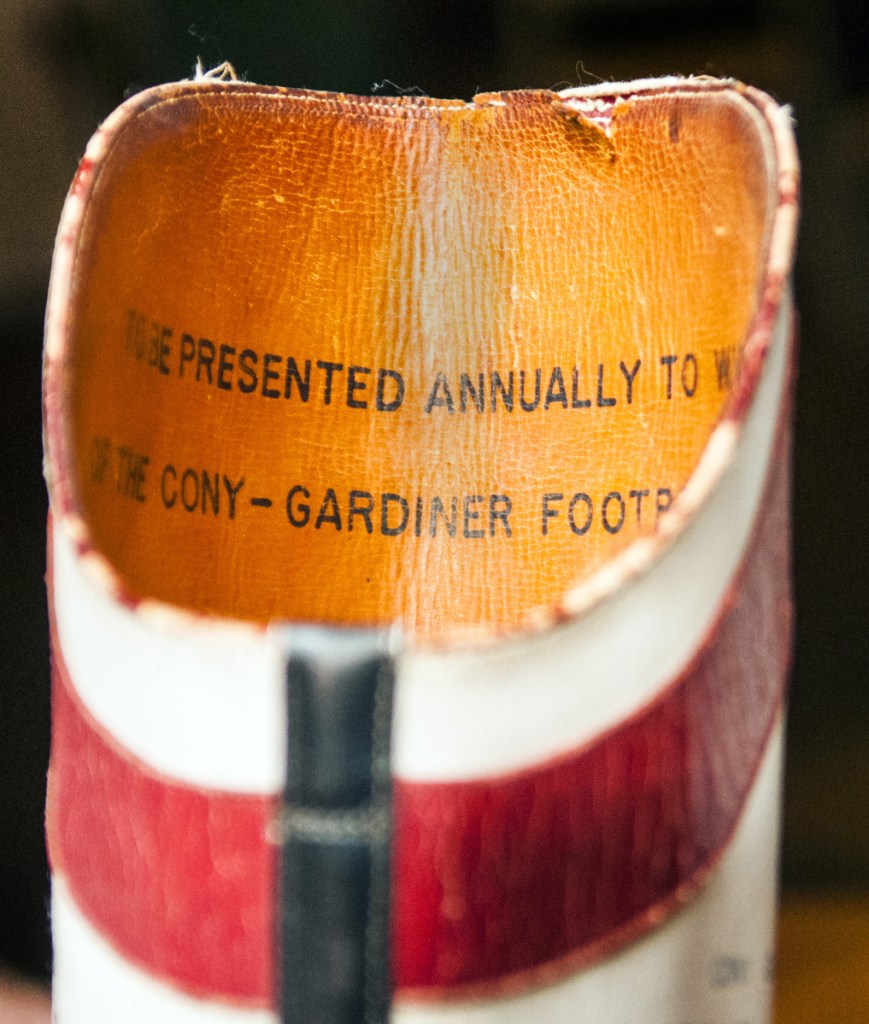

Munzing isn’t alone. He’s just a name on a long list of them, before and since, who associated their career with how they did against that team up or down the Kennebec. Cony-Gardiner is headed for its 141st rendition, and the rivalry has stayed strong, stayed passionate and stayed intense.

“You get between those lines, you get to game day, and the rivalry is still there,” Cony athletic director Paul Vachon said. “There isn’t any doubt in my mind.”

It has, however, changed. Those involved in the rivalry, be it as players, coaches or fans, point to a time when the bad blood simmered to a point of hatred between the schools and communities, when the matchups were preceded by the pomp and circumstance of bonfires, parades and rallies, and when the crowds that turned out for the game easily reached four or five thousand onlookers.

Football was king. And Cony-Gardiner was the cap to it all.

“I think there were a lot more activities surrounding it many years ago,” said Gardiner fan Kerry Spurling, 63. “I think it’s less intense now than it used to be, for sure. … It’s definitely a different feel.”

• • •

As the Gardiner-Cony rivalry has aged, it has also mellowed. There is more familiarity, more combining the communities — athletically or otherwise — than there used to be.

“A lot of the kids know each other extremely well now from a lot of them playing on travel teams together throughout the year,” Vachon said. “The respect factor is now better than ever.”

It was a different story years ago. Rallies and parades whipped the respective communities into a frenzy, and ill will was accepted, and even encouraged.

“When I played, it was a rivalry,” said Sam Shaw, a 1966 Gardiner graduate and the Tigers’ current play-by-play announcer. “There were fights, there was everything. … Everybody’s friends. It was different when I played.”

It was standard practice to find a stuffed ram hanging in effigy in the Gardiner gym, or to see a papier-mâché tiger tossed into a fire at Cony. And it didn’t stop there.

“We used to have guards on the field the nights before a game, to make sure it wasn’t invaded by Gardiner, and Gardiner did the same when it was a home game there,” said Meylon Kenney, a teacher at Cony since 1972 and former Rams coach. “There have been some experiences in which letters were burned in the field. … It got exuberant.”

There was also room for good will, however. Even into the early 2000s, captains would switch schools for a day, attending classes and walking the halls on enemy turf.

“I remember doing the captain swap myself during my senior year, going up into Cony, which was really kind of weird,” Munzing said. “Being in the school, because they were always the enemy.”

• • •

Gardiner tight end A.J. Chadwick had a grandfather, three uncles and two cousins play in the Cony-Gardiner game. He’s heard story after story about the activities that used to lead up to the game, and how special they were.

“It was so much bigger of a thing back then, I think,” he said. “I wish they did (still do the events). I wish we had rallies Friday before the game, or we all got together for something.”

The grandiose celebrations began to die down around the time Cony moved to its current location in 2006, and reversing course would be difficult. One reason that administrators point to is a shifting culture; the other sports have grown in popularity, making it tougher to put such an overwhelming focus on the football team — a trend that has affected the buildup to other long-standing rivalries across the nation. “Do I have a Cony-Gardiner rally, do I have a rally for a quarterfinal game for field hockey next week?” Vachon said. “We try to make it fair for all the teams if we possibly can do that. And back then, there weren’t as many teams.”

“You had less going on back in my time. The Cony-Gardiner football game was it,” Gardiner coach Joe White said. “You have more going on (now), and everyone’s trying to make sure everyone gets an equal amount of notoriety.”

Bonfires, rallies and parades were also easier to arrange in the more relaxed culture of the 20th century.

“If you’re going to have a bonfire, where are you going to have it? Are you going to have it on school ground?” Vachon said. “Do you need a fire permit? Do you need a gathering permit? Does your insurance policy cover these? A lot of people don’t understand, those are the types of things you need to look into.”

• • •

Where the game hasn’t changed, however, is on the field. The school spirit blowouts may be a thing of the past, but for the people who make it to the game, the intensity runs as high as it did back in 1950, 1970 or 1990.

“Society’s changed a great deal. There are other interests,” Kenney said. “But if you like football and you’re an avid fan, it’s the same as it was. The people that go to the games are just as avid as they were way back when.”

Even Gardiner and Cony alums with fond memories of pep rallies and celebrations say the rivalry hasn’t needed them to flourish.

“I really think it’s special even without that,” White said. “If the kids don’t see it or experience it the same way that we did 20, 25 years ago, they’re not going to miss it.”

The players agree.

“It’s basically the biggest part of our season,” Chadwick said. “From a little kid standpoint, you always go to the Gardiner-Cony game. It’s just something that you would always do. Now that you’re playing it it, it’s just a totally different experience.”

It’s been a conference game, an interclass game, an exhibition game, and it’s been played in the heat of August and cold of November. The latest chapter comes tonight, and no one sees it slowing from there.

“It’s all going to be decided on that field. Stories will begin again and that’s what will keep the tradition going,” Vachon said. “Cony-Gardiner will always be a great tradition.”

“It doesn’t matter who’s in (Class) B or who’s in C,” Kenney said. “You can print that in big letters. It doesn’t matter, as far as Cony and Gardiner are concerned, when they meet, who is B and who is C. It’s the Gardiner-Cony game, period. And it will go on to the end.”

Drew Bonifant — 621-5638

dbonifant@centralmaine.com

Twitter: @dbonifantMTM

Send questions/comments to the editors.