NEW YORK — A training program for the next generation of morticians and undertakers is testament to a change that is slowly remaking the funeral business.

Sixty of the 75 students in the program at the State University of New York at Canton are women, and those numbers are no fluke.

In 2017, nearly 65 percent of graduates from funeral director programs in the United States were female, according to the American Board of Funeral Service Education. That’s the highest number ever recorded by the board. Women are being drawn in record numbers to a profession in which, just a few decades ago, it was rare for anyone but men to work.

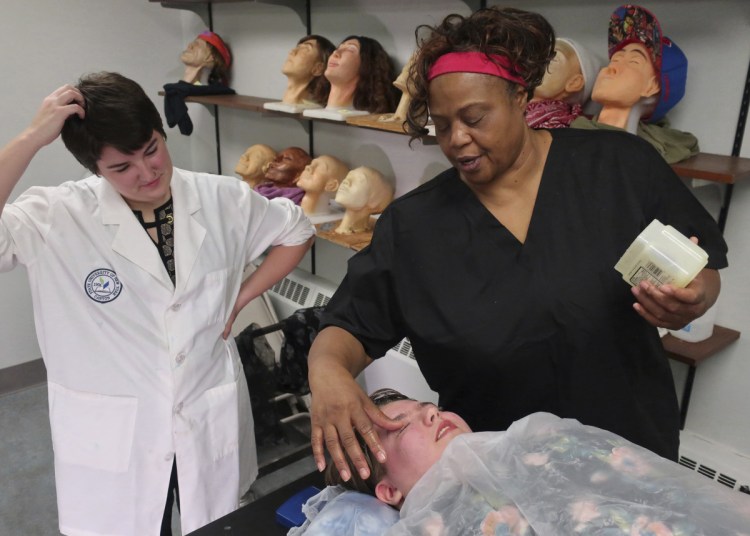

A life mask on a classmate helps the students learn how to restore facial features lost to illness or trauma.

Women coming out of the SUNY Canton program, though, say that for all the progress, they still encounter barriers.

While a majority of people looking to enter the profession are women, 74 percent of morticians and funeral directors are still men, according to 2016 U.S. Census Bureau data.

Stereotypes about women not being strong enough to lift coffins, or worries about exposing pregnant workers to embalming chemicals, make some male funeral home owners reluctant to hire women.

“I feel like that’s a staggering issue that women face in this industry,” said funeral services student Anna Deloriea, 20. “When you go for your residency, which is a long-term internship for a year to get your license, a lot of funeral directors stop you and they are like, ‘I wanted a man’ because they think a woman can’t lift as much.”

Darien Frederick, 21, who graduated from the SUNY Canton program last year and is now a funeral director at Cleveland Funeral Home in Watertown, New York, said some customers still have qualms about women, too.

“I did have a family come in and say they did not want any female funeral directors running their funeral,” Frederick said. “And you can respect those wishes, and that’s fine, and I understand that’s how the older generation was. I’m not hurt by it, but those stigmas are changing.”

Funeral director Darien Frederick adjusts a coffin display at Cleveland Funeral Home in Watertown, N.Y.

Through the early Victorian era, caring for the dead was very much a women’s role in the U.S.

Death care took place in the home, more often than in institutional settings, and preparing a body for burial was a family matter.

That began to change during the Civil War, when embalming fluids allowed families to bring dead soldiers home from the battlefield. And embalming necessitated a scientific education, from which women were then being systematically excluded. Men quickly came to dominate the new death-care industry, as did a false notion that women were too squeamish or emotional to handle death.

David Penepent, director of the funeral services program at SUNY Canton, said that while some of those issues are fading, women face other barriers when entering the profession, like low pay and impatient bosses during residency training.

“If the current generation of funeral home owners don’t start taking and treating women with the respect and dignity that they deserve, there is going to be a time to pass on the funeral home, and there is going to be no one there to buy it,” Penepent said.

Anita Bennet, a student at SUNY Canton, said she sees opportunity in a changing funeral market in which more families are seeking cremation, alternative wakes and natural or nontraditional burials.

Women, she said, are great at helping people deal with grief.

“You can never understand how a person truly feels,” Bennett said. “But you can always let them know that you’re there and that if they need someone to go through it with them you’re there.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.