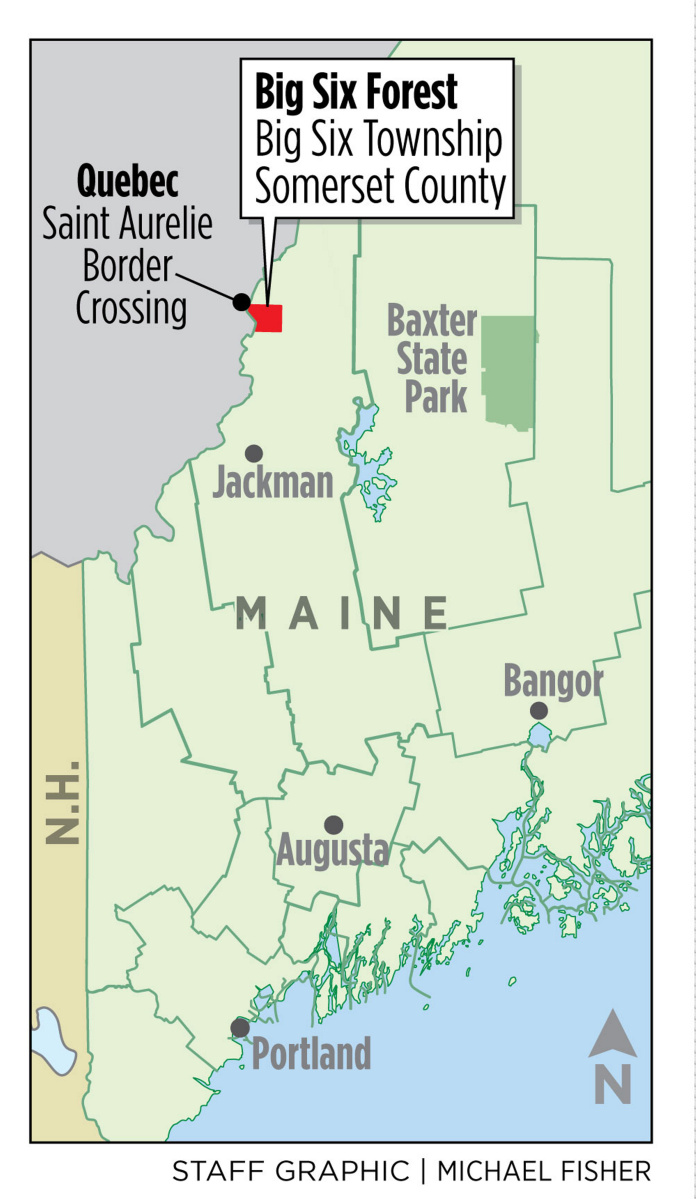

AUGUSTA — A 23,000-acre forest north of Jackman that yields 25 percent of the state’s maple syrup could still qualify for $3.8 million in federal funding despite being rejected by a state land conservation program.

In November 2017, members of the Land for Maine’s Future board passed over the “Big Six Forest” project for funding after opponents raised concerns about the lack of public access to the remote parcel via road except through Quebec. The decision followed higher-than-usual scrutiny of a project that got caught up in the political tensions over land conservation during the LePage administration.

But the Big Six Forest had already qualified for $3.8 million from the federal Forest Legacy conservation program because of its status as one of the largest maple “sugarbushes” in the U.S. and its outsize contribution to Maine’s maple industry. More than 14 months later, the landowner is working with a conservation group and the state to finalize the deal in a way that doesn’t involve matching funds from the state.

“From our perspective, the funds are awarded and now available,” said Jason Kirchner, public affairs officer for the U.S. Forest Service’s eastern region. “It is up to the state and those partners to determine how to move forward.”

Those “partners” – landowner Paul Fortin of Madison, The Trust for Public Land and the Maine Bureau of Parks and Lands – are now proposing a “bargain sale” that would allow Fortin to donate a chunk of the land’s value in order to tap into the $3.8 million in federal Forest Legacy funds.

“It’s the exact same project except the financing is different,” said J.T. Horn, senior project manager for The Trust for Public Land.

ISSUES OVER ACCESS

Located along the Maine-Quebec border, the Big Six Forest includes 17,000 acres of traditional working forest but also 4,500 acres of maple trees that have been extensively tapped for sap collection. Several years ago, the roughly 340,000 maple “taps” in Big Six lands produced 110,000 gallons of maple syrup worth more than $6 million on the retail market.

Supporters of the conservation project note that Big Six accounted for 24 percent of Maine’s syrup production and 3.4 percent of the U.S. total.

But critics pointed out that nearly all of the maple sugarbush is leased by Canadians who sell much of their syrup in bulk to regional wholesalers who market the final product as “Made in the U.S.A.” rather Maine-made. They also dismissed claims in the Forest Legacy application that the property’s proximity to more urban areas of Quebec Province – including Quebec City, just 90 minutes away – made it valuable as potential camp lots.

It was issues over access, however, that sank the project with the Land for Maine’s Future board.

Most Maine residents who recreate or work in the Big Six Forest cross into Canada north of Jackman – a trip that requires a passport nowadays – and drive through several Quebec towns before re-entering via a logging road border station. The only option within Maine is to drive several hours along a series of rough logging roads.

The $3.8 million approved by the U.S. Forest Service in fiscal year 2016 covered 75 percent of the $5 million costs to purchase conservation easements that would protect the sugarbush in perpetuity. Fortin, The Trust for Public Land and the state had sought $1,250,000 from the LMF program to cover the required 25 percent match to leverage those federal funds.

But during a closely watched LMF process, board members questioned the “exceptionality” of the property as well as the lack of easy access from Maine. All projects that receive LMF funding – which comes from voter-approved bonds – must provide public access for recreation. As a result, Big Six was not among the 15 projects approved for a slice of the $3.2 million LMF funding available at that time.

“Imagine how this will play to the people looking at this from the outside?” appraiser and LMF board member Fred Bucklin said during the November 2017 meeting. “We paid $1,250,000 for a piece of property that we can’t even get to? It doesn’t seem to make any sense to me.”

There was also speculation that the administration of Gov. Paul LePage – a vocal critic of Maine’s conservation community – only supported the Big Six project because Fortin was a political supporter of the governor. LePage had held up LMF bonds as political leverage and criticized individual projects. And after leading the nation in Forest Legacy funding, Maine failed to submit applications for funding for several years during the LePage administration

‘BARGAIN SALE’

Fortin could not be reached for comment last week. But Horn said The Trust for Public Land and the other partners “are quite committed to seeing this through” despite the disappointment of losing LMF funding.

The exact terms of the transaction have yet to be finalized, pending federal approval for an appraisal of the land. But Horn said Fortin would offer to sell the development rights on the land – via conservation easements – at a “bargain sale” of the appraised price. When combined with a small amount of private funding, that would equal the 25 percent match necessary to free up the $3.8 million in federal funding.

Fortin would retain ownership of the land while the Maine Bureau of Parks and Lands would be the “holder” of the conservation easements.

“The entire property would be conserved and the maple sugaring there, which is what makes the property unique, would be protected in perpetuity,” Horn said.

At least one vocal critic of the Big Six deal remains opposed, even without the inclusion of LMF or other state dollars.

“There shouldn’t be any money going into it at all,” said Bill Jarvis, a licensed forester from Jackman.

Jarvis dismissed arguments that Quebec residents were clamoring for camp lots in Big Six. There’s little to no pressure from Canadians seeking camps in the Jackman area, and it is even easier to access from Quebec than Big Six, Jarvis said.

And he was even more dismissive of suggestions that Fortin could cut down the maple sugarbush and sell it for timber or other wood products. That’s because the harvesters would have to remove all of the tubing, pipes and other syrup-related infrastructure in the 4,500-acre sugarbush before they could even get to low-quality trees that are littered with taps, nails and other intrusions.

And then there is the steady stream of revenue flowing from the maple sugar leases.

“All it was, in my opinion, was a threat to get the money,” Jarvis said. “If you look at the revenue he is getting from these tap leases, why would he ever kick them out?”

But Lyle Merrifield, president of Maine Maple Producers Association and owner of Merrifield Farm in Gorham, said the property is too important to Maine’s maple industry to risk losing it.

While most of the producers working in Big Six are Canadian, they sell the resulting syrup in Maine or elsewhere in the U.S., buy equipment and pay taxes in the U.S. There are also several generations of maple sugaring heritage on the property that would be lost, not to mention one of the largest sources of bulk maple syrup in the country.

“It would have a sizable impact on our industry if we lost that area,” Merrifield said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.