WAYNE — Steve and Molly Saunders heard the same stories from the thousands of migrants seeking asylum in the U.S. from Central America.

“It is not safe there.”

“I did not want the gangs to take my child.”

“My house will be taken away because my husband got sick, and I could not find work.”

“My brother was murdered.”

The Wayne couple answered a call for help from the Peace Corps in April to assist at a shelter in El Paso, Texas, the first stop for asylum seekers released from detention centers by the U.S. Border Patrol and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

The call was unlike anything they’d received from the Peace Corps, where they had been volunteers in El Salvador in 1968 to 1969. And with fluency in Spanish, they knew their services would be needed.

Their experience comes amid a national immigration crisis that involves ongoing debate over security at the border with Mexico, federal immigration law and how to serve an increasing number of families from sub-Saharan Africa making along and dangerous journey through Central America and Mexico to the southern U.S. border, where they ask for asylum. In Maine, the Portland Expo was converted into a 24-hour temporary shelter nearly two months ago to accommodate the sudden arrival of hundreds of African migrants who crossed the Mexico border to seek asylum.

The Saunders — using their own money for travel and lodging — volunteered for more than two weeks at the Annunciation House in El Paso, where they helped hundreds of migrants daily reach sponsors in America. The Annunciation House, funded by the Catholic Church and private donors, received the migrants from ICE after they were released from holding camps at the border.

At first, these vetted migrants were let go at bus stations to find their own way to their sponsors. Then, after local transportation said no to the overcrowding — and confusion — in their terminals, the migrants were released into El Paso’s city streets.

More confusion followed.

“The people we were dealing with almost entirely were people from small towns up in the mountains of Guatemala and Honduras just subsistence living,” said Steve.

The Saunders described how most were indigenous, uneducated people living in small mountain towns, and therefore uncomprehending about the culture not only in the U.S., but in civilization that had access to technology and information.

“They didn’t know what they were coming to,” he said. “They had never flown in a plane or done this type of travel, never been in a country where nobody spoke Spanish.

“You could spot the few people who had grown up in the city and had the opportunity to have regular education. They were savvy about coming into the U.S.”

Ruben Garcia, the director of the Annunciation House, told ICE no: Do not dump these people in the streets; bring them to the shelter.

VOLUNTEER SPIRIT

The Annunciation House is a shelter that primarily houses the undocumented homeless, but it was not equipped to support so many people.

This was when the call for help was released, and the Saunders responded.

“The appeal to the Returned Peace Corps Volunteers was sent by Bishop Mark Seitz, the Catholic bishop of El Paso,” said Mary Fontana, volunteer coordinator for Annunciation House Inc.

“… Tap into the volunteer spirit that motivated you to serve in the past and to come to El Paso to assist us,” the appeal said. “As this situation continues, it is straining the ability of our local community to respond.”

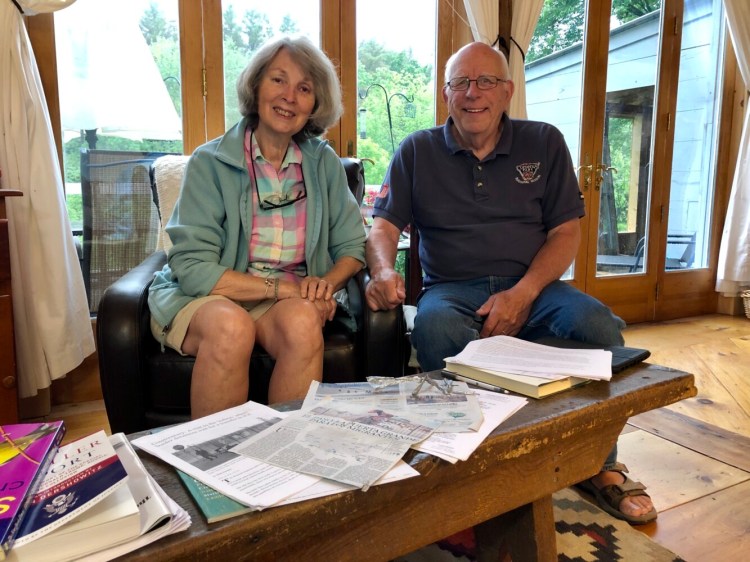

Molly Saunders holds bow ties made from Mylar emergency blankets worn by asylum seekers whom she and her husband assisted while volunteering at shelters in El Paso, Texas, this spring. The newspaper clippings, brought back to Wayne from their trip, show the migrants crossing the concrete canal that is the Rio Grande from Juarez, Mexico, into El Paso. Kennebec Journal photo by Abigail Austin

Steve, who said he had a heart attack in 2018, said the opportunity spoke to him.

“I decided to do the things I have been putting off,” he said, “and one of them is volunteer work.”

By the time the Saunders reached El Paso, the Annunciation House was renting local hotels and had opened several buildings. That included a warehouse, called “Casa Romero” by the shelter, where the Saunders would volunteer.

Annunciation House received 500 to 700 asylum seekers daily at their multiple shelters, they said — up to 1,000 toward the end of their work. According to the appeal, it normally helped 300 people a week.

After spending up to nine or 10 days in the detentions sleeping outside in cramped spaces with minimal food, they arrived at the shelter, stripped of their belongings — identification, money, cell phones, backpacks, extra clothes, shoelaces, belts, socks, even hair ties, Molly said.

She said they were resourceful. She held up a strip of mylar cut from an emergency blanket and tied into a bow. It had been a little girl’s hair tie.

“They made shoelaces like this, too,” Molly said.

“We do not know why,” the Saunders said migrants told them about the length of their stays.

“What happened in detention was really humiliating and very unhealthy,” said Molly.

They speculated why they were treated so harshly, and could only conclude that the Border Patrol and ICE agents were trying to discourage them so word would get back down that “you shouldn’t come.”

“By the time they got to us, they were dehydrated, hungry, dirty and completely exhausted,” Molly said, “and this includes small children, even 8-month-old babies.”

MIGRANT INTAKE

Steve said that when they arrived at the shelter to volunteer, they were thrown right into the mix with little to no orientation because there were very few volunteers, only six to eight volunteers at a time.

“(Border Patrol) would disgorge 80 to 100 people at our shelter,” he said. “The first thing we would tell them was, ‘This is not a detention center; you are safe.’”

During intake, each family would receive a number, he said, and volunteers would collect basic information, like names and ages, along with a contact for a sponsor in the U.S.

The volunteers would contact the sponsor, who would be expecting the call after being reached while the asylum seekers were in detention, and direct them to send plane or bus ticket confirmation numbers.

And then the volunteer would hand the phone to the families for brief emotional exchanges, the Saunders explained.

“I finally made it,” they overheard.

Many broke down into native dialects that the Saunders could not understand.

After the contact, the Saunders said volunteers fed the families and gave them clean bedding and clothing along with toiletries before showing them to male and female dormitories. Exhausted, most went right to sleep.

The following day, they said, the asylum seekers eagerly awaited news of travel confirmation from the sponsors. Most had it, and the shelter would bus them to the airport or bus station, where now they were allowed since that confusion had been sorted.

Those who did not receive a confirmation number and who had to stay at the shelter longer were responsible for cleaning and preparing food, according to the Saunders.

Asylum seekers prepare meals for other countrymen at Casa Romero. Contributed photo by Molly and Steve Saunders.

“We were telling them, ‘This is your house, you’re welcome to everything here, but you have to do it,” Steve said.

“They were always enthusiastic (to help),” Molly said, “but never once did I find someone who knew how to run a washer machine.”

The number of fights or disagreements or stealing?

“Zero,” said Molly.

At any one time, there were 150 people at Casa Romero, the Saunders explained, and there was a constant hurry managing the flow because as soon as some left, more would arrive.

“That was the cycle every day,” Steve said.

ON THE RUN

The migrants, the Saunders believed, were not seeking to start a new life in the U.S. They wanted to make money, which they would send back to their families in southern Mexico and Central America, and live in the country only temporarily.

“They are running from climate change, drought, crops are failing, the gangs are moving out in the towns,” said Molly.

“Honduras and Guatemala are failed states,” she said. “The cartels have taken over to the point where the police are so corrupt that there is no more rule of law.”

She said faith drove the people — faith that God would get them out of their country, to the U.S. And that faith gave them certainty that in several years, after they could earn money, they would be able to return to a safer country, that the danger would be suppressed.

While the asylum seekers shared their experiences in detention centers and their hopes for their futures, they were quiet about their trek through Mexico to the Rio Grande.

“They obviously had suffered a great deal getting to the border,” Steve said.

In recent months, migrants have discovered safety in numbers, the Saunders said, arriving in large numbers to border crossings with the help of “coyotes,” Mexican smugglers, who charged them thousands of dollars to reach the border — double to cross it illegally.

If the migrants crossed illegally on the outskirts of the metropolitan El Paso and Juarez with the help of coyotes, they would first have to survive the dangerous Chihuahuan Desert, known for rattlesnakes, scorching temperatures, and lack of moisture except during monsoon season, when the bulk of its annual 9 inches of rain falls.

The coyotes put dangerous pressure on the migrants and their families left behind for pay, which was promised when asylum seekers started work in the U.S.

A day’s drive from Dallas and Houston and almost 5,000 feet in elevation, El Paso is divided by the rocky Franklin Mountains and circled by the Rio Grande and Juarez, Mexico, to the south; Fort Bliss, a U.S. Army base to the east; and New Mexico to the west and north.

The Saunders said people they spoke with during their commute between the shelter and their hotel said that they were unaware of the large increase of asylum seekers traveling through their city.

“They were unaware of all this going on,” Steve said. “They were not affected by it directly — there were not people running through the streets or backyards.

“They were sympathetic,” he said.

Around the city, the Rio Grande flows first through New Mexico, irrigating farmland, then around the Franklins into canals. The canals, which are in places concrete, are often shallow or empty, creating a safe place to cross.

The asylum seekers after crossing the river, would run across around 100 feet of American soil, Molly said, to the fence where they would wait to surrender to Border Patrol agents, who would give them a credibility of fear interview and take them to the detention center.

Because of the easy way to cross, “El Paso became the new Ellis Island,” said Molly. “Word got out that it was a safe place to enter America.”

SHORT REWARD

In the months since returning from their trip to El Paso, the Saunders have learned that the amount of migrants coming through the Annunciation House has dropped to as low as 25 daily.

New policy changes to the Migrant Protection Protocols, also known as Remain in Mexico, by the Trump administration now calls for migrants to wait in Mexico for appointments with a judge to determine their asylum status — appointments months out, according to the Associated Press.

Migrant children can be seen in a game room in an Annunciation House shelter in El Paso, Texas, this spring. Contributed photo by Molly and Steve Saunders

But Molly thinks it is more like a year that they could wait.

“The Trump Administration keeps throwing stuff out and trying it, and it’s all failing miserably,” said Steve. “Everything they do is to try and scare people from coming.”

“There are about eight or 10 shelters in Juarez,” said Molly, “and they were all full three times capacity when we left.

“If they’re busing people to Juarez, they’re just dropping them on the streets,” she said.

This means they are being stripped of supplies, the same way they came to the Annunciation House.

“Juarez is getting unsafe again,” Steve said. “There are thousands of immigrants there who are vulnerable to kidnappings and extortion.”

“We have loved to travel around Mexico,” said Molly, describing their annual trips where they immersed into the culture and loved the people.

The couple most recently traveled there in 2017 to Yucatán, “but we stopped going. It is just not safe anymore because the police are really corrupt.”

Now the Saunders are asking the question: what would be so bad about having asylum seekers come to the U.S.?

They say these migrants do not have the intention of living on welfare or using American reserves for support. They want to work in a country where they can earn $10 per hour rather than $1 a day, salaries they can send home to their families once they pay off Coyotes.

“What is the harm in treating them well and letting them come here and treat them as refugees?” Molly asked.

Although the problem at the border is 2,000 miles away from New England, the Saunders say it is an American problem.

“What we have to realize up here is that it is not safe for us to have our neighbors go completely down the drain and turn into complete catastrophe states,” said Molly. “As Americans, we don’t seem to think that is a problem. It is like we are an island.

“These states are going to get worse and worse, and it is going to have an effect on us.”

The Saunders are both 75. They are not sure if they would make such an excursion to volunteer again.

Despite the long hours of work and exhaustion, the reward was short — they do not know if the people they helped made it to their sponsors, and what would happen years or months into the future when they would return to their homes.

“It is very painful to think of all those people that we came to know in a short period of time very intensely that they are just not there anymore,” Steve said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.