By his own admission, Chris Newell is not a writer. The former director of the Abbe Museum wrote a book, so he’s a published author.

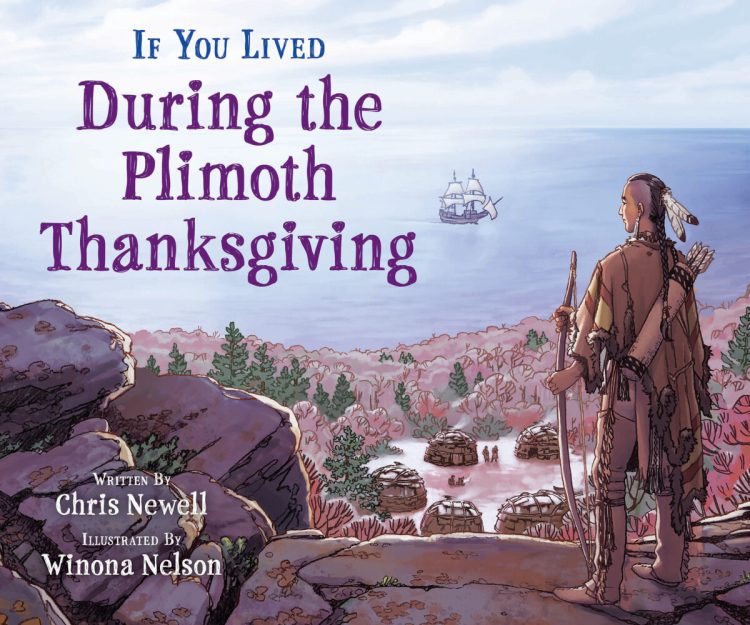

But the process of writing “If You Lived During the Plimoth Thanksgiving,” published last week by Scholastic Press and geared toward kids in first to fourth grades – but appropriate for anyone who wants to learn a history of Thanksgiving from the perspective of Indigenous people – made him appreciate the challenges of putting a sensitive and personally important story out into the world.

“I do write a lot of stuff, but not like this. Writing a book almost feels in a way like you are opening a vein and exposing a part of yourself, not just to a class of 30 kids, but now to the world,” said Newell, a Passamaquoddy and educational consultant, whose specialties include the impact of the landing of the Mayflower in 1620 on the Wampanoag people. “There was an intense amount of anxiety that I had to fight through in getting the first draft done. That is why I say I am not a writer.”

The anxiety was worth it. The book has received a lot of attention. Kirkus Reviews gave it a coveted starred review, making it eligible for its annual Kirkus Prize. The Kirkus reviewer noted that Newell writes about the “all-too familiar” elements of the Thanksgiving story, and expands it by contextualizing the Mayflower voyage around the Doctrine of Discovery, which opened up lands not occupied by Christians to Europeans, the Great Dying that preceded the Mayflower, killing vast numbers of Indigenous people with diseases carried from prior explorations.

“Refreshingly, the lens Newell offers is a Native one, describing how the Wampanoag and other Native peoples received the English rather than the other way around,” Kirkus writes.

Newell is hopeful about the book’s impact on the kids who read it and the people those kids influence.

“I am trying to change the world for the better,” he said in a phone interview from his home in Connecticut. “Publishing a book with someone who has the reach of Scholastic, the potential for the positive impact is tremendous. That is what gets me over my fear. I foresee that if I put my heart and soul into it, I can impact the lives of children in a positive way and bring them farther along than their parents’ generation.”

Newell, who grew up in Indian Township, became the first Wabanaki director of the Abbe Museum in Bar Harbor in March 2020, just before the pandemic, and resigned this September, citing, in part, his separation from his family in Connecticut. The Abbe explores the history and culture of the Wabanaki people in its exhibitions. Newell wrote “If You Lived During the Plimoth Thanksgiving” during the pandemic while living alone in a sparsely furnished rental in Ellsworth.

The 96-page book is part of Scholastic’s “If You Lived” series, which has been around for generations and attempts to answer kids’ questions about events in U.S. history. The stories are told in a question-and-answer format, and the books are geared toward classrooms and homes. Scholastic hired Newell to update an earlier version of the book, which was titled “If You Lived During the First Thanksgiving.”

The First Thanksgiving is both a misnomer and a myth, Newell said.

“The story of the Mayflower as a foundational myth of the country’s beginning erases the harsh realities of disease and aggression experienced by Native peoples as Europeans settled their colonies in America,” he writes in his introduction to the book. “It also erases the current existence of Native peoples who live in the United States today. The Mayflower landing is an important piece of history that needs exploration. But in its exploration, all perspectives should be sought. The story of the Mayflower landing is different depending on whether the storyteller viewed the events from the boat or from the shore.”

Newell centers the story on the Wampanoag people who were on shore when the Mayflower landed in modern day Plymouth, Massachusetts, after a previous stop on what is now Cape Cod.

“Wampanoag leaders knew from experience that the large wooden ships from Europe sometimes meant big trouble. The English settlers on the Mayflower did not announce their arrival to the Wampanoag people. There was no contact or communication with any Wampanoag leadership to arrange for their arrival and settlement. It is usual for people from one country to negotiate with the leaders of another country before settling there. The English did not believe that they needed to do this when coming to Wampanoag country,” Newell writes. “Wampanoag people kept a close watch on what the English were doing, but they did not approach.”

The following spring, in 1621, Samoset, a visiting Wawenock sachem who knew some English, approached the colonists one afternoon and said, “Welcome,” then went on to speak with them into the evening. The friendly encounter changed everything for the English, Newell said, because it led to an alliance between the English and the Wampanoag people. That alliance resulted in a shared meal after the fall harvest. But the celebration was not a thanksgiving, which the colonists celebrated as part of their religion and involved fasting, not feasting.

Newell writes that the term “the First Thanksgiving” is a mistake of history. The feast of 1621 was not called the First Thanksgiving until 1841, when a Boston writer used the term in a footnote in a book about the settlement that became Plymouth. The inaccuracy was repeated over time and eventually accepted as fact in popular U.S. culture.

“By 1870, schoolbooks were telling the story of the First Thanksgiving, and by the late 1880s, fiction writers were telling a version of the story that became the famous tale we know today,” Newell writes. “It has been known as ‘the First Thanksgiving’ by Americans ever since.”

Thanksgiving became a national holiday in 1863, as a way to help heal the wounds of the Civil War. But the national holiday represents an open wound and a day of mourning for the Wampanoag and other Indigenous people, Newell said.

In the book, he points out fundamental differences between the cultures of the Wampanoag and the settlers, creating context for the conflicts that followed, particularly in how they viewed the land – as a something that provides resources for all versus something for an individual to own.

The artist Winona Nelson, a member of the Leech Lake Band of Minnesota Chippewa now living in Philadelphia, illustrated the book. Newell praised her illustrations for their detail and accuracy. “She did not create generalized depictions of how Wampanoag villages looked and she did not do generalized depictions of how the English looked. She did a tremendous amount of research and she got it right. I was so pleased when I saw the art and blown away at how good she did getting it right,” he said.

For Newell, the book represents a continuation of his educational consultancy, which involves teaching “hard histories to non-Native audiences in a way that is forward thinking and beneficial to all human beings together,” he said.

As challenging as the book was to write, it won’t be his last. Newell is finishing the first draft of another Scholastic book, an update of “If You Lived During the American Revolution,” also told from a broader and more inclusive perspective than the original, as well as a book of fiction for little kids about growing up on an Indian reservation in Maine. Newell plans to create a character, roughly based on his father, to tell a larger story about living simply.

“Even though they didn’t have electricity or running water, their life was rich. As kids, they never knew they were actually poor until kids from off the reservation told them they were poor,” Newell said of his father and his community. “The book will be focused on our values, with a character living a full life full, rich in culture and language, who is then confronted by someone from a different culture, who thinks a lack of money means something is missing in your life, when it actually doesn’t. They come to a common understanding about what wealth really means.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.