VASSALBORO — About a quarter-mile down Main Street from the Vassalboro Historical Society sits a white barn, its driveway unplowed from winter snowfall. After trudging through nearly a foot of crusty snow, you enter the dark, unlit barn through a side door and walk past old desks and chairs to a flight of stairs.

To your left, among barrels, sleds, sleighs, and even more old desks and chairs is a series of metal shelves. On the bottom shelf is a black plastic trash bag. Open the bag, and out comes a pair of trophies, appearing shiny and new despite their time in cold storage. They’re known in sports nomenclature as “Gold Balls,” but they have more of a bronze/copper tint to them. One reads, “STATE CHAMPIONS CLASS D 1978” and the other reads, “STATE CHAMPIONS CLASS D 1979.”

For all intents and purposes, this is Oak Grove-Coburn School’s trophy case. The school shuttered in 1989 under a crushing debt. Now, what people called “the castle on the hill” is home of the Maine Criminal Justice Academy in Vassalboro, its brick towers still dominating the rolling campus.

OGC, as it was widely known, held an auction in summer 1989 in an attempt to satisfy its last payroll. Grandfather clocks, coin-operated washers, rugs and even old basketballs were sold off. The trophies escaped that fate and were given to the historical society.

“They may be cold and in storage, but we take care of them,” said Jan Clowes, the tireless president of the Vassalboro Historical Society, who has done much to keep the memory of OGC alive.

• • •

Oak Grove-Coburn was the product of a 1970 merger between a pair of financially struggling schools, Vassalboro-based Oak Grove School — a Quaker co-ed institution-turned-girls “finishing school” — and Coburn Classical Institute, a prep school in downtown Waterville. The new school occupied the Oak Grove building off Route 201.

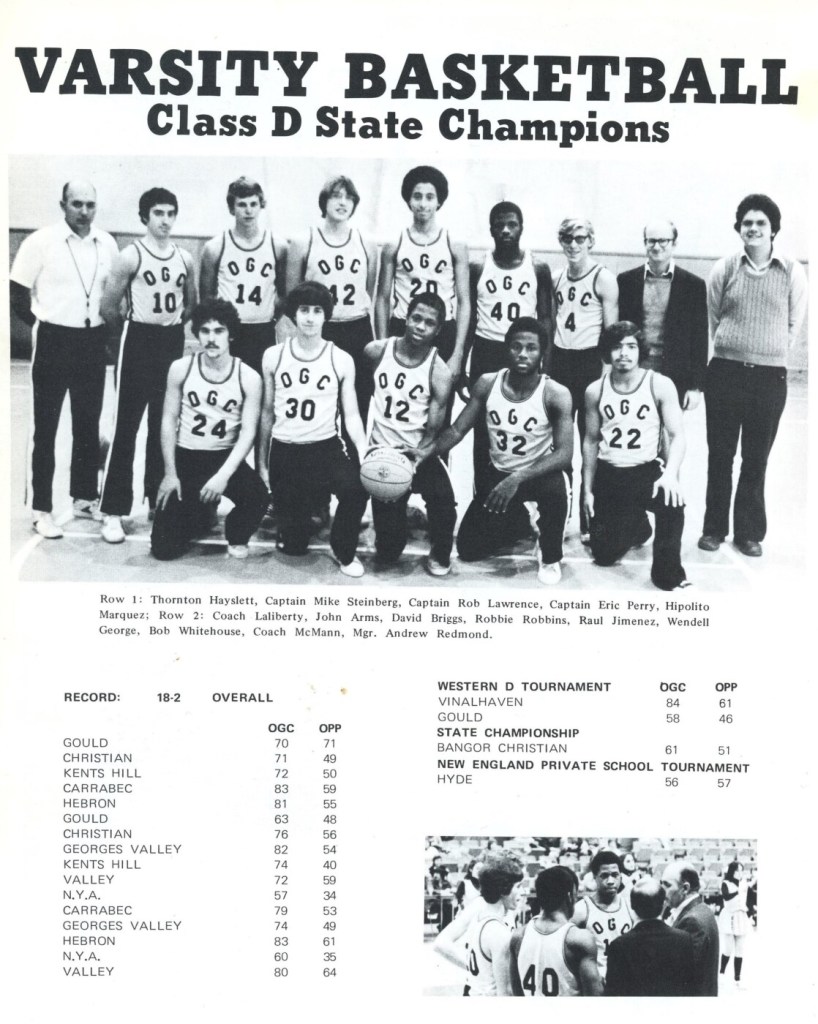

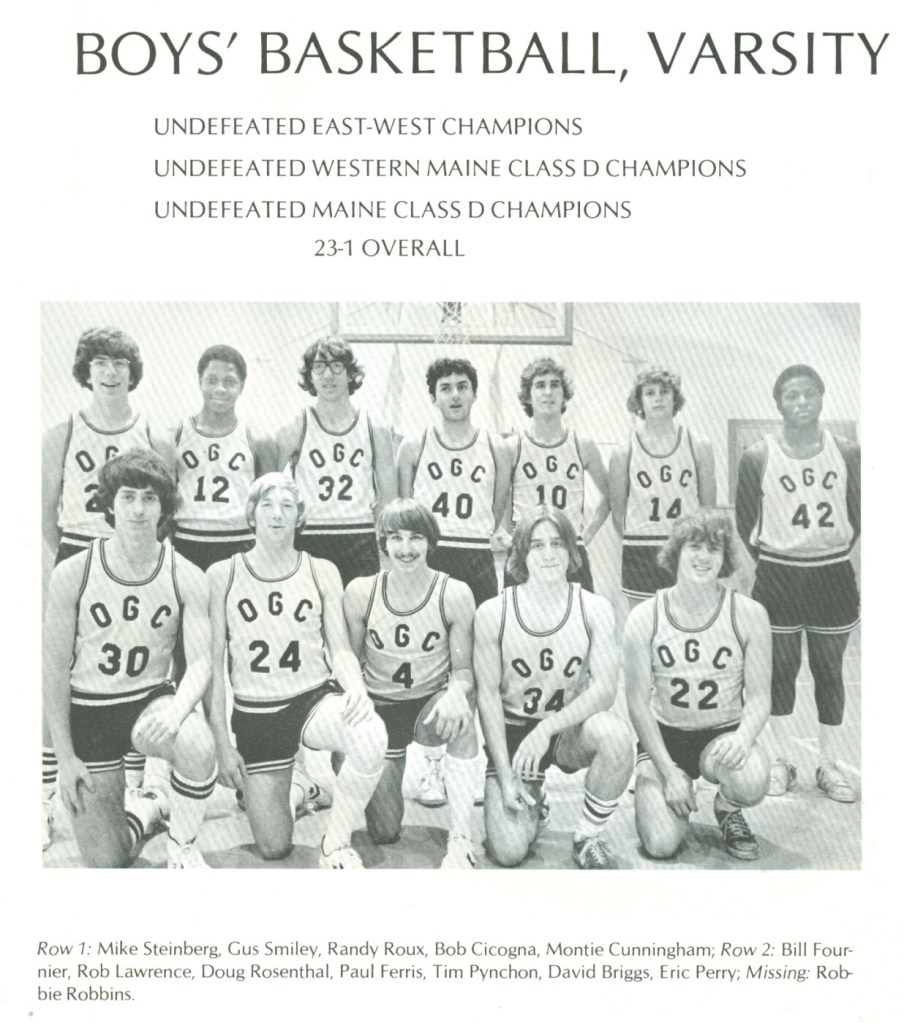

While OGC remained in the red during its 19-year existence, the boys basketball program turned out some profitable teams, particularly from 1977-85, when the Tigers won five Class D West titles, capped with state crowns in 1978 and ’79. The school’s reputation, however, went beyond the court.

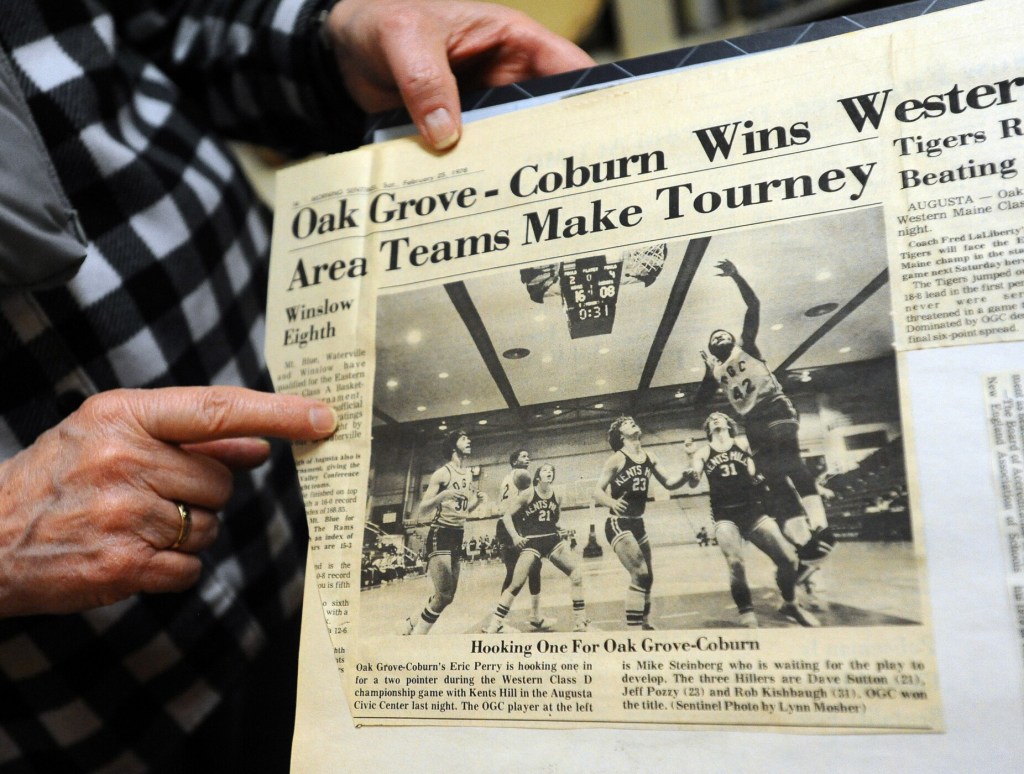

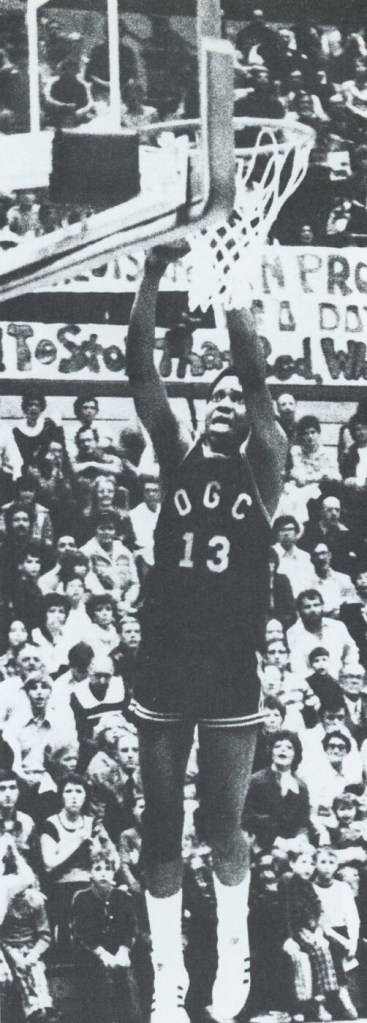

Oak Grove-Coburn’s Mike Steinberg (30) attempts a layup against Jonesport-Beals in the 1978 Class D boys final at the Augusta Civic Center. OGC won, 66-60. Photo provided by Mike Steinberg

OGC was far from your typical high school. Classes were small in size, and teachers were not afraid to experiment with unconventional approaches, according to a 1989 Morning Sentinel article. The school had day students from Vassalboro and nearby communities, but it also had boarding students who hailed from around the country and the world. (In 1989, the school’s first Japanese exchange student returned to Vassalboro to visit her host family, only to learn OGC was closing.)

“It made it a fascinating place to go to school,” said Mike Steinberg, a member of OGC’s 1978 and ’79 championship teams and whose father was the school headmaster. “We had college professors’ kids and we had farmers’ kids. I think you ask almost anybody and they’ll say it was a welcoming, diverse place.”

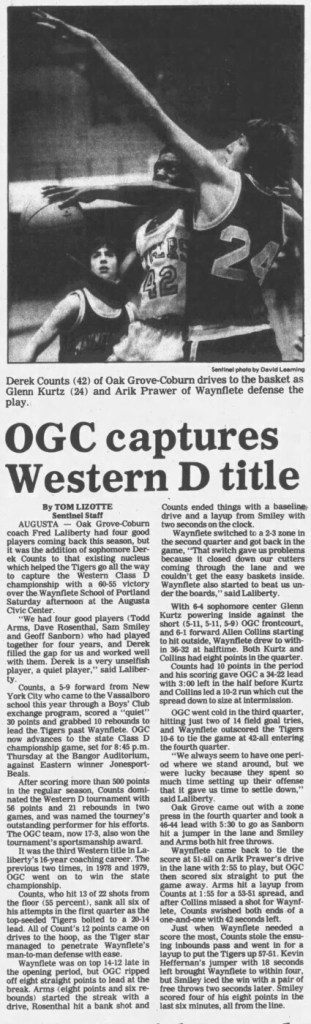

Larry Lowe, a New York City native and a member of OGC’s 1983-85 state finalists, arrived in Vassalboro as part of a Boys’ Club program in New York designed to empower inner-city youths in search of a quality education. Teammate Derek Counts, who set the Maine schoolboy scoring record in 1985, also was a product of the program.

“My impetus to go to Oak Grove was to have the best education possible,” Lowe said, “and basketball just happened to be a sport I grew up with, and was something I gravitated toward.”

It was in this atmosphere a basketball powerhouse — a unique-for-Maine mix of Black and white student-athletes — began to flourish under the guidance of coach Fred LaLiberty, who had roamed the sidelines since 1967 when it was still part of Coburn Institute.

The Tigers played more like kittens in their early years, winning just once in 51 games from 1970-73. But OGC gradually climbed the Class D West standings and stormed to the 1978 title, going 22-0 and topping favored Jonesport-Beals — a longtime powerhouse that had won six of the last eight Gold Balls — 66-60 in the final before 2,500 fans at the Augusta Civic Center. Bill Fournier, a 5-foot-11 senior guard, and like Steinberg a Vassalboro resident, scored a game-high 26 points.

Other standouts included Doug Rosenthal, a 6-2 center from Waterville, and a pair of New York City natives, Rob Lawrence and Eric Perry.

Jan Clowes, of the Vassalboro Historical Society, displays some of the books that feature newspaper clippings from the 1978 and 79 Oak Grove-Coburn boys basketball title teams. Rich Abrahamson/Morning Sentinel

Fournier and Rosenthal graduated after the season, but OGC’s dominance continued unabated. The Tigers rolled past Vinalhaven and Gould in the Class D West tournament at Augusta and topped Bangor Christian 61-51 in the state final at the Bangor Auditorium. Lawrence scored 20 points and Perry added 15 points and 11 rebounds.

While the Gold Ball was the big prize, the regional title win over Gould in Augusta was almost as sweet, Steinberg said.

“Beating Gould was a big thing, because they were kind of like our rivals,” said Steinberg, now 62 and a teacher of civil rights litigation at the University of Michigan law school. “We were undefeated except for our very first game, which we lost to Gould. We really wanted to beat them in the Western finals.”

OGC had an unusual home-court advantage that psyched opponents out long before they ever got to Augusta. The gymnasium, a relic from the Oak Grove “finishing school” days, was built more for physical education class than varsity competition. The court eschewed wood for a hard, multipurpose floor. One side of the court was right up against the wall, which necessitated the creation of a second line inside the out-of-bounds line so players could have enough room to inbound the ball.

With money always an issue at OGC, improvements were slow to happen.

“I remember we sold light bulbs throughout Waterville and Winslow to raise money to get glass backboards,” Steinberg said. “That was my freshman year.

Oak Grove-Coburn boys basketball captains, from left, Rob Lawrence, Mike Steinberg and Eric Perry, pose with he 1979 Gold Ball after they defeated Bangor Christian at the Bangor Auditorium. Photo provided by Mike Steinberg

“Going to Augusta was very special because our gym was tiny. We played in front of a couple thousand (in Augusta), but it felt big-time.”

The gym also featured a glass wall that gained condensation whenever the heat was on, which of course in winter was all the time. The drips of water would seep onto the floor and the players would start slip-sliding away.

“We got used to it; it was like the old Boston Garden, constantly mopping the floor and everything,” said Lowe, who now lives in Ghana, where he is chief marketing officer of a vitamin and supplement company. “I’m surprised we didn’t kill ourselves during that time.”

• • •

The titles were not without some controversy. The sight of multiple Black players on the court in mostly-white Maine in the 1970s and ’80s led to charges of recruitment, something OGC people denied then and deny now.

“I always thought they recruited before I came here,” Charles Hotham, who took over as Tigers coach when LaLiberty died in 1983, told the Kennebec Journal in 1984. “But all the kids have to fulfill academic requirements to come here.”

Kathy Hanson, director of admissions at OGC, said as much in a letter to the Morning Sentinel in March 1985.

“I admitted three Black students from New York because they met our academic standards, and I felt we could offer them an excellent education,” Hanson wrote.

Added Lowe: “All of the kids who came from New York City and the Boys’ Clubs program were on academic scholarships. It was not basketball. We were all very good students, actually. They tested the children and so forth. … Basketball was just a happy bonus and a happy experience for us.”

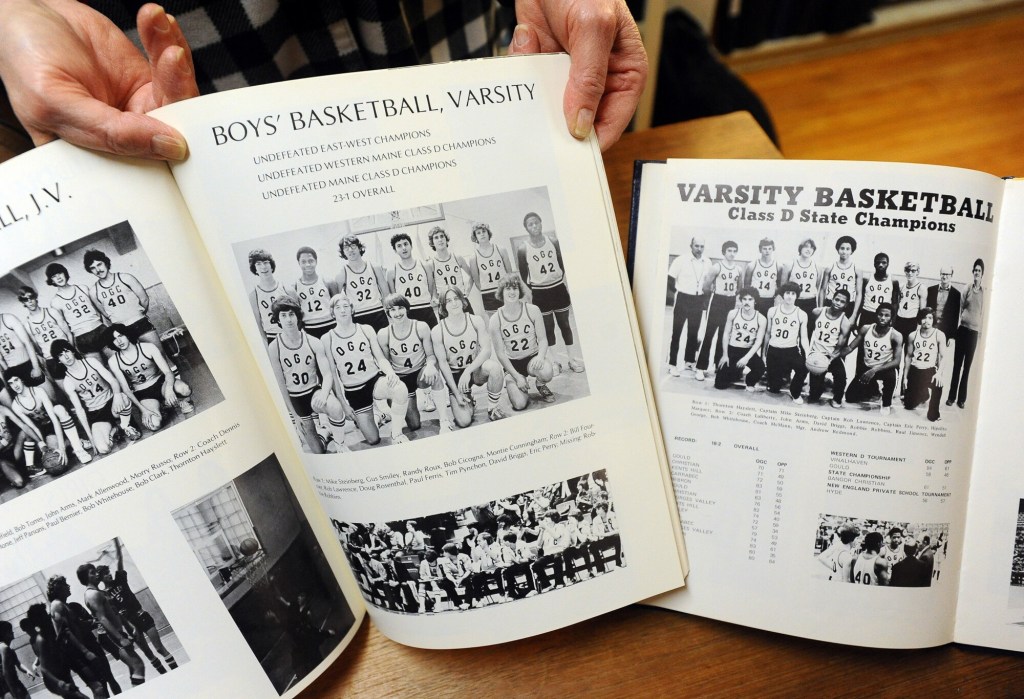

These yearbooks from the Oak Grove-Coburn School feature boys basketball teams that won Class D championships in 1978 and 1979. The books are kept at the Vassalboro Historical Society in Vassalboro. Rich Abrahamson/Morning Sentinel

After a few subpar years, OGC roared back in 1982-83 thanks to the arrival of another New York City native, the 5-foot-10 Counts, who quickly became one of the most talked-about players in the state. You name it, he could do it.

“He was a great passer, a great shooter — he could shoot anywhere from mid-range to a little bit deeper,” said Lowe, who compared his style with that of 1980s Detroit Pistons star Isaiah Thomas. “His drive was phenomenal. He could leap and rebound. He had a nice vertical leap. He was very, very strong. He was silky smooth.

“We used to call him ‘The Claw,’ because you would see this sea of people going to the rebound and then all of a sudden, rising, you’d see Derek’s hand just coming out above everyone and just snatching the rebound.”

In just three seasons, Counts set an all-time Maine scoring record with 2,310 points. In 1984-85, he averaged 33.4 points per game and was named the Morning Sentinel’s Class C-D player of the year. In nine playoff games, he averaged 33.3 points and 13.8 rebounds per game.

The soft-spoken Counts went on to play four years at the University of New Hampshire.

“You would never hear one word from his mouth during almost the entire game,” Lowe said. “I don’t care if he was frustrated, I don’t care if someone would call him crazy, there was no yelling or screaming. He was just quiet, composed — kind of a silent assassin.”

The 1977-78 Oak Grove-Coburn boys basketball team photo from the school’s yearbook. Photo provided by Mike Steinberg

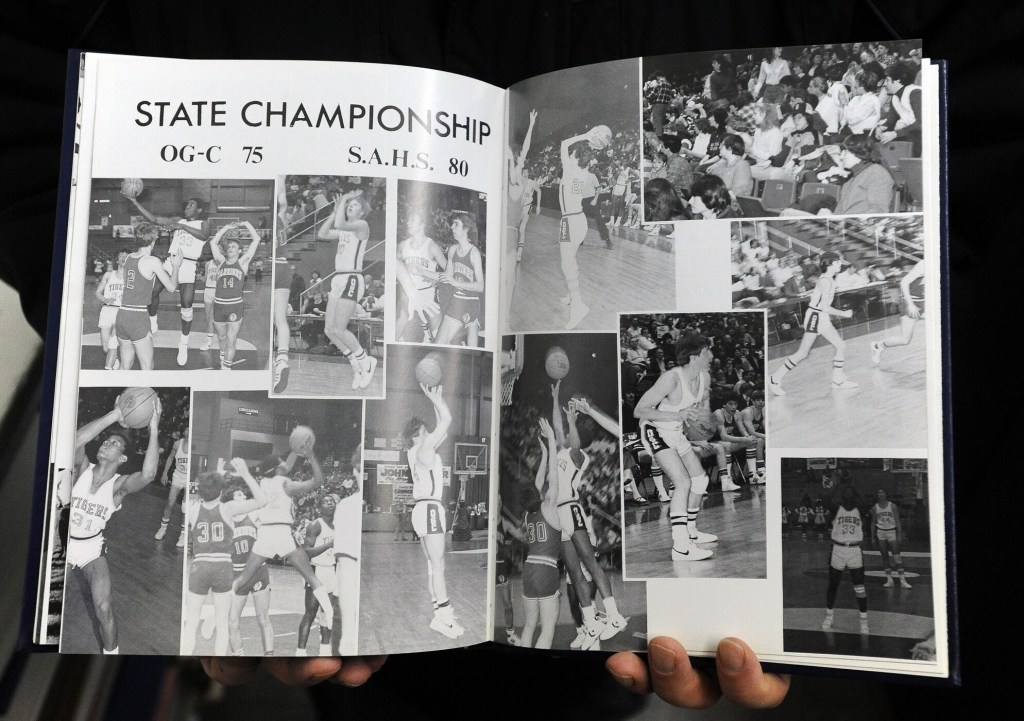

The only achievement that eluded Counts was a state championship. OGC won three straight Class D West titles but fell in the final each time. The 1985 loss, an 87-83 overtime loss to Jonesport-Beals at the Bangor Auditorium, still stings the OGC alumni to this day.

Many people, then and now, felt the officiating hurt the Tigers even more than Robert Alley’s 42-point, 18-rebound effort. Three OGC starters — Counts (39 points, 11 rebounds), Rich Dunston (26 points, 15 rebounds) and Will Mitchell — fouled out.

While Hotham, the head coach, said private schools don’t always get the calls they deserve when playing public institutions, others felt it was something more sinister.

“I still can’t shake the notion that the Tigers were the victims of a hose-job by the referees,” the Morning Sentinel’s Tom Lizotte wrote in the March 7, 1985 edition. “It seemed Jonesport-Beals benefitted from virtually every close call in the second half.

“But,” he added sarcastically, “I’m sure the fact that OGC starts three Black players from New York City has nothing to do with it.”

Counts, Dunston and Lowe are Black.

As the Jonesport-Beals players celebrated, Lowe and his teammates sat on the court, crying and distraught. A Jonesport-Beals parent walked up to Lowe.

“She said, ‘I am so sorry this happened to you. This is just not right. I am so sorry that you had to experience this,’” Lowe recalled. “We had people crying and everything. It was really a travesty of justice.”

Added Steinberg: “It wasn’t easy being Black and playing in Maine. We used to play at Jackman and Bingham, and those were the worst. The games were on Friday night, and there’d be the drunk guys from town who would come and there’d be some racial slurs. But the team itself was rock-solid. We had each others’ backs.”

Jan Clowes, of the Vassalboro Historical Society, peers out from behind the two Gold Balls that Oak Grove-Coburn boys basketball team won in 1978 and 79. The Class D Gold Balls are stored at the historical society in Vassalboro, Rich Abrahamson/Morning Sentinel

Another damaging loss came four years later, when the school closed after failing to recover from what the Morning Sentinel reported as a $1 million shortfall. The school closed, most everything in the school was auctioned off and Oak-Grove-Coburn was no more.

“It was a punch in the gut, because it was such a great time in our lives,” Steinberg said. “The teachers were amazing, and the relationship between the faculty and the students was strong. For me, personally, it was my childhood. I grew up there, and it was really hard. … It hurt then, it still hurts now.”

• • •

The Gold Balls may be in cold storage, but they’re hardly forgotten. In 2012, OGC’s basketball alumni reunited at the Maine Criminal Justice Academy gym — the same cramped place where they played in olden times — for a game between the “Old Tigers” from the 1970s and the “Young Tigers” from the ‘80s. (The Old Tigers won and got to parade a Gold Ball again.) Another reunion is planned for this summer.

A sign from the Oak Grove-Coburn gym is displayed at the Vassalboro Historical Society in Vassalboro on Tuesday. Rich Abrahamson/Morning Sentinel

The school’s alumni maintain a Facebook page that has nearly 600 members.

“They are the most connected alumni ever,” said Clowes, whose historical society has preserved yearbooks, scrapbooks, signs and just about anything else related to the school.

And for the people who went there, the OGC experience went far beyond sports.

“People love it,” Steinberg said. “I don’t know that many people who love their high school, but you talk to most Oak Grove-Coburn alums and they say it was a magical place.”

Added Lowe: “Oak Grove’s story is one that’s deeper than the court, which is what I loved about the school. In the Facebook group, people still express ridiculous amounts of admiration and stories across demographics across class, across race. And basketball was kind of a way to bind us all together and root for one another together.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.