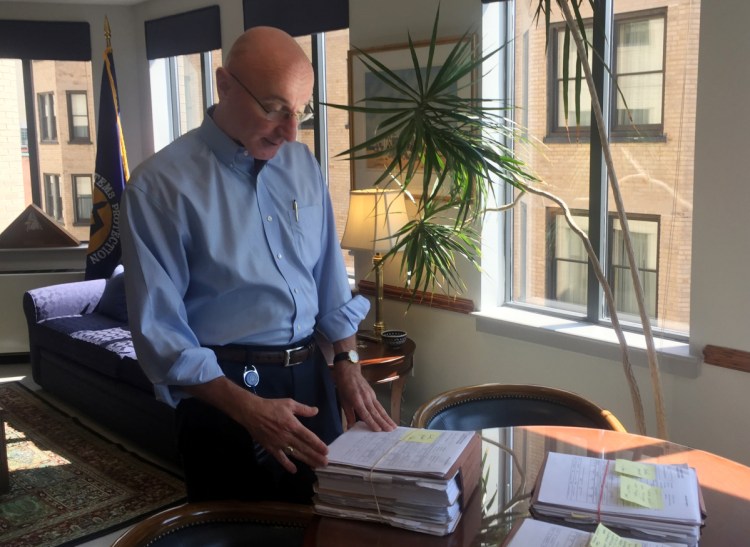

WASHINGTON — Mark Robbins gets to work at 8:15 each morning and unlocks the door to his office suite. He switches on the lights and the TV news, brews a pot of coffee and pulls out the first files of the day to review.

For the next eight hours or so, he reads through federal workplace disputes, analyzes the cases, marks them with notes and logs his legal opinions. When he’s finished, he slips the files into a cardboard box and carries them into an empty room where they will sit and wait. For nobody.

He’s at 1,520 files and counting.

Such is the lot of the last man standing in this forgotten corner of Donald Trump’s Washington. For nearly two years, while Congress has argued and the White House has delayed, Robbins has waited to be sent some colleagues to read his work and rule on the cases. No one has arrived. So he toils in vain, writing memos into the void.

Robbins is a one-man microcosm of a current strand of government dysfunction. His office isn’t a high-profile political target. No politician has publicly pledged to slash his budget. But his agency’s work has effectively been neutered through neglect. Promising to shrink the size of government, the president has been slow to fill posts and the Republican-led Congress has struggled to win approval for nominees. The combined effect isn’t always dramatic, but it’s strikingly clear when examined up close.

“It’s a series of unfortunate events,” says Robbins, who has had plenty of time to contemplate the absurdity of his situation. Still, he doesn’t blame Trump or the government for his predicament. “There’s no one thing that created this problem that could have been fixed. It was a series of things randomly thrown together to create where we are.”

Robbins is a member of the Merit Systems Protection Board, a quasi-judicial federal body designed to determine whether civil servants have been mistreated by their employers. The three members are presidentially appointed and Senate-confirmed for staggered seven-year terms. Pay is about $155,000 a year. After one member termed out in 2015 and a second did so in January 2017, both without replacements lined up, Robbins became the sole member and acting chairman. The board needs at least two members to decide cases.

That’s a problem for the federal workers and whistleblowers whose 1,000-plus grievances hang in the balance, stalled by the board’s inability to settle them. When Robbins’ term ends on March 1, the board probably will sit empty for the first time in its 40-year history.

It’s also a problem for Robbins. A new board, whenever it’s appointed and approved, will start from scratch. That means while new members can read Robbins’ notes, his thousand-plus decisions will simply vanish.

“There is zero chance, zero chance my votes will count,” the 59-year-old lawyer says, running his fingers over the spines of leather-bound volumes lined up neatly on a shelf. Inside are the board’s published rulings. None of the opinions he’s working on will make it into one of them.

“Imagine having the last year and half of your work just … disappear,” he said.

‘STILL DOING MY JOB’

Robbins, a Republican, was excited when Trump won the election. The president chooses two board members of his or her own party, and the Senate minority leader picks a third. Robbins assumed he’d finally be in the majority after years of serving alongside Democrats, soon able to write opinions rather than just logging dissent.

No such luck.

Trump was in office a year before he nominated two board members, a pair of Republicans, including Robbins’ replacement. A third nominee, a Democrat, was named three months later, in June.

Months went by and still no confirmation vote. Robbins said he was told the Democrats were refusing to confirm the two Republicans by unanimous consent, insisting instead on a full debate for each. In late September, the Senate Homeland Security and Government Affairs subcommittee that screens nominees told Robbins it probably would not be able to confirm the appointees before the end of the current Congress. That meant that the entire process, which typically takes several months when there are no complications, will begin again come January, with no guarantee the nominees will be the same.

Robbins sees the futility of the piles of paper and empty offices. But he’s determined to keep the trains running, even if he’s the only one on the ride.

“It’s not like I’m sitting around on the sofa watching soap operas and eating bonbons. I’m still doing my job,” he said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.