CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. — NASA’s Opportunity, the Mars rover that was built to operate for just three months but kept going and going, rolling across the rocky red soil, was pronounced dead Wednesday, 15 years after it landed on the planet.

The six-wheeled vehicle that helped gather critical evidence that ancient Mars might have been hospitable to life was remarkably spry up until eight months ago, when it was finally doomed by a ferocious dust storm.

Flight controllers tried numerous times to make contact, and sent one final series of recovery commands Tuesday night, along with one last wake-up song, Billie Holiday’s “I’ll Be Seeing You,” in a somber exercise that brought tears to team members’ eyes. There was no response from space, only silence.

Thomas Zurbuchen, head of NASA’s science missions, broke the news at what amounted to a funeral at the space agency’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, announcing the demise of “our beloved Opportunity.”

“This is a hard day,” project manager John Callas said at an auditorium packed with hundreds of current and former members of the team that oversaw Opportunity and its long-deceased identical twin, Spirit. “Even though it’s a machine and we’re saying goodbye, it’s still very hard and very poignant, but we had to do that. We came to that point.”

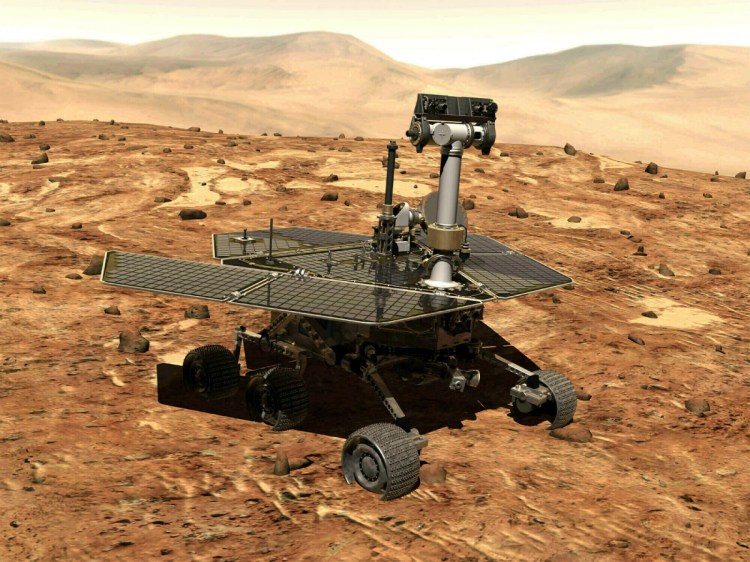

The two slow-moving, golf cart-size rovers landed on opposite sides of the planet in 2004 for a mission meant to last 90 sols, or Mars days, which are 39 minutes longer than Earth days.

In the end, Opportunity outlived its twin by eight years and set endurance and distance records that could stand for decades. Trundling along until communication ceased last June, Opportunity roamed a record 28 miles (45 kilometers) and worked longer than any other lander in the history of space exploration.

This photo released Feb. 5, 2004, made by one of the rear hazard-avoidance cameras on NASA’s Opportunity rover, shows Opportunity’s landing platform, with freshly made tracks leading away from it. Opportunity rolled about 11 feet that day, the first day it had moved since it left the lander five days earlier. Engineers commanded Opportunity to turn slightly during the drive, to test how it steers while rolling through the martian soil.

Opportunity was a robotic geologist, equipped with cameras and instruments at the end of a mechanical arm for analyzing rocks and soil. Its greatest achievement was discovering, along with Spirit, evidence that ancient Mars had water flowing on its surface and might have been capable of sustaining microbial life.

Project scientist Matthew Golombek said these rover missions are meant to help answer an “almost theological” question: Does life form wherever conditions are just right, or “are we really, really lucky?”

The twin vehicles also pioneered a way of exploring the surface of other planets, said Lori Glaze, acting director of planetary science for NASA.

She said the rovers gave us “the ability to actually roll right up to the rocks that we want to see. Roll up to them, be able to look at them up close with a microscopic imager, bang on them a little bit, shake them up, scratch them a little bit, take the measurements, understand what the chemistry is of those rocks and then say, ‘Oh, that was interesting. Now I want to go over there.'”

Opportunity was exploring Mars’ Perseverance Valley, fittingly, when the fiercest dust storm in decades hit and contact was lost. The storm was so intense that it darkened the sky for months, preventing sunlight from reaching the rover’s solar panels.

When the sky finally cleared, Opportunity remained silent, its internal clock possibly so scrambled that it no longer knew when to sleep or wake up to receive commands. Flight controllers sent more than 1,000 recovery commands, all in vain.

With project costs reaching about $500,000 a month, NASA decided there was no point in continuing.

Callas said the last-ditch attempt to make contact the night before was a sad moment, with tears and a smattering of applause when the operations team signed off. He said the team members didn’t even bother waiting around to see if word came back from space — they knew it was hopeless.

This March 31, 2016, photo shows a dust devil in a valley on Mars, seen by the Opportunity rover perched on a ridge. The view looks back at the rover’s tracks leading up the north-facing slope of Knudsen Ridge, which forms part of the southern edge of Marathon Valley.

Scientists consider this the end of an era, now that Opportunity and Spirit are both gone.

Opportunity was the fifth of eight spacecraft to successfully land on Mars, all belonging to NASA. Only two are still working: the nuclear-powered Curiosity rover, prowling around since 2012, and the recently arrived InSight, which just this week placed a heat-sensing, self-hammering probe on the dusty red surface to burrow into the planet like a mole.

Three more landers — from the U.S., China and Europe — are due to launch next year.

NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine said the overriding goal is to search for evidence of past or even present microbial life at Mars and find suitable locations to send astronauts, perhaps in the 2030s.

“While it is sad that we move from one mission to the next, it’s really all part of one big objective,” he said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.