The number of deaths in Maine is on pace to eclipse the number of births for the second straight year, in a trend that could have implications for the state’s economy.

U.S. Census data released Thursday show that from July 2011 to July 2012, deaths in Maine outnumbered births, 12,857 to 12,754.

Those numbers probably will be adjusted, but they highlight Maine’s status as one of the nation’s oldest states and the fact that fewer families appear to be having children.

The 2011 calendar year was the first in at least 70 years in which more people died in Maine than were born here, according to data from the state’s Office of Vital Records.

The new census figures suggest that when the state numbers for 2012 are complete, they will show the trend continuing.

While the trend nationally is more obvious in Maine and West Virginia — the only other state where deaths exceeded births from July 2011 to July 2012 — 1,135 of the nation’s 3,143 counties, more than one-third, are experiencing what economists call a “natural decrease.” That’s up from roughly 880 U.S. counties, about one-quarter, in 2009.

Eleven of Maine’s 16 counties had natural decreases from July 2011 to July 2012, with the largest percentages in Washington and Piscataquis counties.

State Economist Amanda Rector said the natural decreases are an economic challenge for the state.

“Population growth is directly related to economic growth,” she said. “Businesses that want to move here or expand need to be able to fill their workforce needs.”

Ryan Neale, the Maine Development Foundation’s program director, said one of the state’s challenges now is finding enough able-bodied workers to fill jobs. He said that while workers could be found through a change in natural patterns, that’s unlikely to happen, given Maine’s aging population.

More likely, Neale said, the solution will entail bringing in workers from other states or countries.

“We have a lot of desirable qualities as a state, but people need to be assured that they can find a career here,” he said.

Data from the Office of Vital Records show that Maine’s birth rate has ebbed and flowed, from the baby boom of 1946 to 1964, to fewer births throughout the 1970s, then to a smaller boom in the late 1980s.

From 1990 through 2002, the number of births in Maine dropped steadily each year, from 17,314 to 13,549. Beginning in 2002, the rate went back up, to a high of 14,152 in 2006.

The number has decreased every year since then. During the period from 2005 through 2011, the number of births decreased 10 percent.

The 12,694 births in 2011 was the lowest yearly total on record, dating back to 1940.

Rector, the state economist, said families often put off having children in times of economic turmoil. History shows that once economic conditions improve, birth rates rise, sometimes dramatically.

Maine’s death rate has gone up gradually in the last three decades. From 1950 to 1980, the number of deaths per year averaged about 10,500. From 1980 through 2010, the yearly average was closer to 12,000.

Deaths overtook births in 2011, and that trend could continue as 70 million baby boomers nationwide grow older.

Liz Thompson, program coordinator for the Southern Maine Agency on Aging, said a recent census study showed that from 2008 to 2020, the number of people 65 or older in Maine is expected to increase 51 percent.

“We’re seeing greater demand for services, particularly inquiries about Medicare,” she said. “There doesn’t seem to be an end in sight.”

Despite increasing deaths, the U.S. population as a whole continues to grow slightly. In Maine, the population increased by 648 residents from 2011 to 2012, less than 0.05 percent.

While population growth is stagnant, the data reveal a continued shift away from rural counties and toward metropolitan centers.

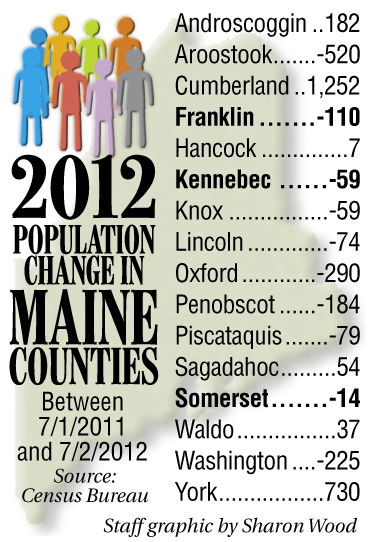

The new census figures show that 10 of Maine’s 16 counties lost population from July 2011 to July 2012, with Aroostook, Piscataquis and Washington counties losing the most by percentage.

All six counties that had population increases were in southern or coastal Maine, with Cumberland and York counties gaining the most people.

Scott Moody, an economist and the director of the Maine Heritage Policy Center, wrote a blog post about Maine’s lackluster population growth, which he called “demographic winter.”

“As net natural population growth moves further into negative territory, it will eventually reach a point where even net in-migration will not be able to compensate,” Moody wrote.

Rector said population shifts will always be dictated by jobs.

The expansion of technology-related industries has made it easier to do some jobs from anywhere, she said, but some areas of Maine still have infrastructure deficiencies that limit that ability.

Send questions/comments to the editors.