Drug companies have long enlisted doctors to serve as de facto spokespeople for specific products, and have paid them handsomely to do so.

However, an increase in disclosures by some drug companies in recent years of the amount they pay doctors – disclosures that will be mandatory by next year – appears to be reducing the amount of money those companies are giving doctors in Maine.

From 2010 to 2012, the amount of money paid by drug companies to Maine doctors for speaking engagements dropped by 60 percent, according to data compiled by ProPublica, an investigative journalism website. Money paid to doctors in Maine for research, usually clinical drug trials, increased by 40 percent from 2011 to 2012.

ProPublica launched its Dollars for Docs initiative in 2010 to track the money drug companies spent to test and market their products. The database was recently updated to include disclosures for 2012, including hundreds from Maine.

The list is not comprehensive because not all drug companies are required to disclose the information yet, but it does offer a glimpse into the financial relationships and incentives between pharmaceutical companies and doctors.

Supporters say those relationships are critical for drug companies, to help them generate industry support for new products, but critics say doctors who take that money run the risk of becoming salespeople for those companies, not educators. Although speaking engagements are legal, they also raise ethical questions about whether physicians who take payments to speak about those products are more likely to prescribe them.

Sharon Treat, a Democratic state representative from Hallowell and executive director of the National Legislative Association on Prescription Drug Prices, said she thinks more disclosure about the financial relationship between drug companies and doctors has changed the way doctors behave.

“Some of these relationships certainly look questionable, but disclosing the information lets the public decide,” she said. “Patients should be able to ask their provider whether they are being paid a fair amount of money to talk about benefits of a drug and then write prescriptions for that drug.”

The health care professionals interviewed for this story did not say what drugs they spoke about or put through clinical trials.

Dr. Jeffrey Barkin, a Portland psychiatrist and president of the Maine Association of Psychiatric Physicians, received the second highest total amount of money for speaking engagements: $63,375 from drugmaker Eli Lilly in 2009; another $31,950 from the same company in 2010; and $18,900 from drugmaker AstraZeneca in 2010.

In an interview with the Press Herald, Barkin said his speaking engagements were never specifically tied to certain drugs. Rather, his talks were about educating other physicians on appropriate diagnoses for psychiatric disorders and about the overlap of physical disease with psychiatric disease and how that can sometimes lead to fragmented care.

Barkin said he has not received any payments from drug companies since 2010, prior to his current employment, and said his feelings about the relationship between doctors and drug companies have evolved.

He said while there are benefits to having doctors, particularly specialists, speaking to other doctors about a particular drug or disease, especially in rural areas, he believes that the cozy relationships often drive up the cost of medications.

Still, even while he was being paid by drug companies to speak, he said he never felt his speaking engagements were a quid pro quo arrangement. “I wasn’t writing more prescriptions for those drugs,” he said.

Marjorie Powell, senior assistant general counsel for the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, said in an email response that a number of factors have affected drug companies’ interactions with physicians over the past years, but she did not elaborate on whether there has been an appreciable decrease in the number of paid speaking engagements.

Scott MacGregor, communications director for Lilly USA, the domestic arm of Eli Lilly, said that employing experts to lead educational forums is a critical part of drug development. He said payments are largely market-driven, depending on the development stage of a particular drug.

The database includes 927 total disclosures in Maine from 2009 to 2012. In some cases, the disclosures were payments made by drug companies to medical practices. In others, the payments were made directly to physicians.

The payments are split into several categories. The most common payment, for travel and meals, represents about 60 percent of disclosures, and it is given when a drug company pays physicians to listen to a presentation about a product. Sometimes, physicians will travel for the presentation; other times, drug company representatives will visit a doctor’s office or practice and buy lunch or dinner. Those disclosures are typically smaller amounts, in the $500 to $1,000 range.

Gordon Smith, executive director of the Maine Medical Association, said companies used to reward doctors with perks, such as all-expense paid golf trips as a sort of quid pro quo. Those days are gone, he said, largely because the American Medical Association updated its code of ethics and because of the increasing number of disclosures by the companies.

Among the findings in the database:

• In 2012, 10 drug companies paid a total of $181,960 to 26 Maine doctors for 44 speaking engagements. The average payout was $4,135, but the range of payments varied from $19,500 down to $291. In 2011, the number of speaking engagements was nearly the same, but the total payout was twice as much, $362,174. In 2010, companies spent $472,110 on 62 speaking engagements.

• Eli Lilly has spent the most money in Maine by far on speaking engagements between 2009 and 2012, paying $571,572 for 37 appearances. GlaxoSmithKline paid for 50 speaking engagements in Maine during that time and spent $256,262.

• Companies spent $788,755 on clinical research in Maine in 2012, an increase from $450,390 in 2011. Merck spent the most, followed closely by Pfizer.

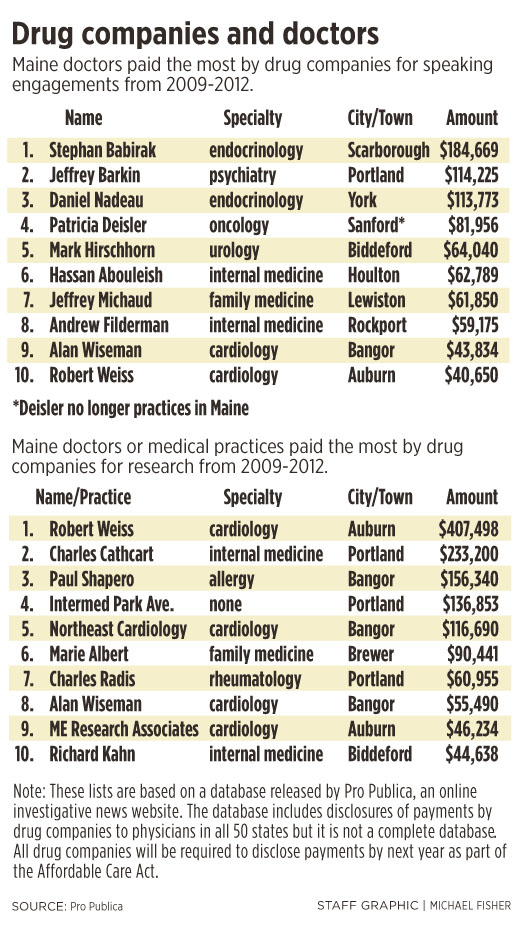

• One doctor, Dr. Stephan Babirak, a Scarborough endocrinologist, received $184,669, the highest total amount paid to a single doctor, for nine speaking engagements between 2009 and 2012. Babirak did not return several calls for comment left over several days.

• Dr. Robert Weiss, an Auburn cardiologist, received $407,498, the highest total amount for research funds between 2009 and 2012.

Weiss, a nationally respected cardiologist, said he was often asked by drug companies to speak about a specific drug or course of treatment. In most cases, he said, he agreed to the request because he had free rein to talk about both the benefits and drawbacks of the drugs.

But now, he said, drug companies have changed those procedures so that before doctors can talk to their peers about a specific drug, they must first review slides provided by the company and talk to the company’s medical officers. Weiss said his recent experiences have been even worse than that, with drug companies’ marketing departments presenting speakers with a script that they are not allowed to deviate from.

“That doesn’t seem respectable,” he said.

Weiss said there will always be doctors willing to speak for a paycheck, even if it means their name shows up in a database tracking doctors who receive drug company payments.

On the research side, Maine doctors received significantly more money from drug companies in 2012 than they did in 2011, although some of that is dependent on the production of new drugs.

Weiss said some of his colleagues have stopped taking clinical research funds because of the increased scrutiny brought on by disclosure, but said he’s proud of his research.

“If you do them well, you’re going to keep getting asked,” he said. “I’ve been doing (research) for 30 years.”

Weiss said that he is not using the research funds to buy himself a vacation home and that almost all the money he’s received from drug companies has gone to pay his 19 employees and cover stipends for patients who participate in the trials.

Critics, however, say research is part of the problem.

Barkin said clinical trials are important to the research and development of any new drug, but they are not all carried out the same way.

“While drug manufacturers have offered tremendous innovation, my concerns relate to potential manipulation of research trial data which has led to instances of abuse and fraud in marketing,” he said. “Also, the bar for approval is often too low, allowing products with little benefit to enter the market.”

Treat said there is pressure to push through clinical trials in order to get drugs on the market before their side effects are fully known.

Weiss, however, said he has not been pressured to approve a drug, and in fact, three-quarters of all the drugs he’s tested have never reached the market.

“That’s part of the reason drugs cost so much,” he said.

Drug companies only started disclosing payments to doctors because of lawsuits brought by former employees who alleged the money was used for unethical, and in some case, illegal purposes.

Starting in 2009, seven drug companies begun posting information on their websites. ProPublica compiled that data into a searchable database beginning in 2010 and recently updated the list to include disclosures from 2012.

However, those lawsuits have not affected all drug companies. The ProPublica database does not quantify exactly how much money is being spent by drug companies. It estimated that the companies in the updated database represent slightly less than half of all prescriptions sold in 2011.

Next year, all drug and medical device companies are likely to be required to report such spending to a federal database, per requirements in the federal Affordable Care Act.

Powell of PhRMA said the industry will benefit from a more complete database because it will include some contextual information to help people understand the nature of the relationships between the companies and doctors.

Eric Russell can be contacted at 791-6344 or at:

erussell@pressherald.com

Twitter: @PPHEricRussell

Send questions/comments to the editors.