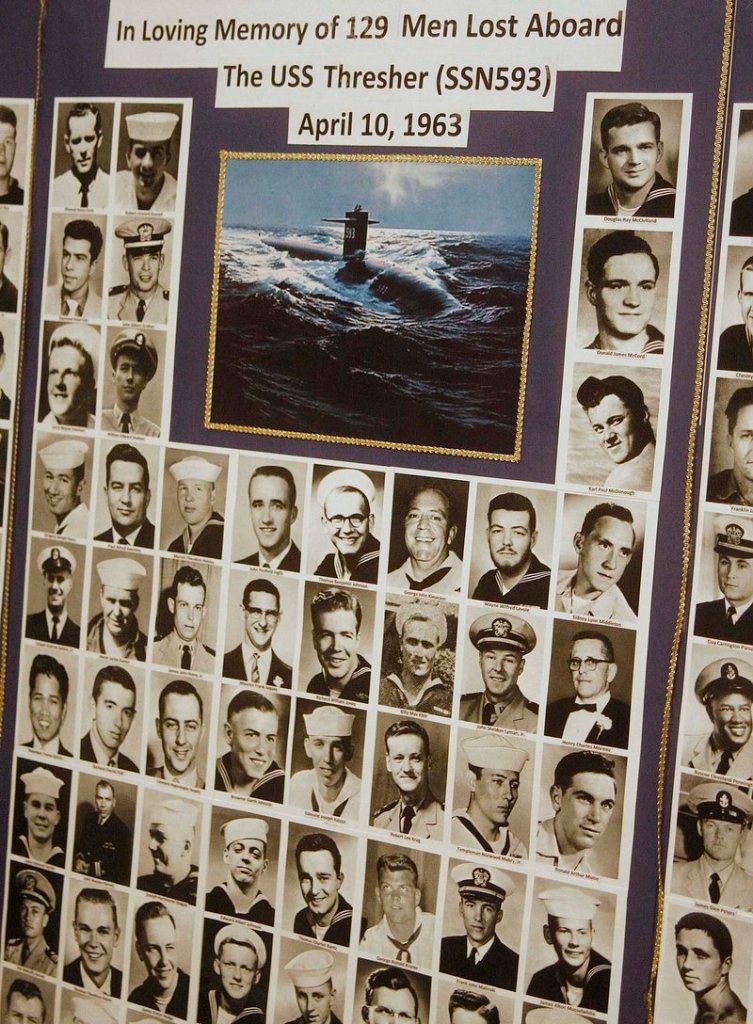

KITTERY — For perhaps a minute or so, the 129 men aboard the USS Thresher probably realized that their submarine would be crushed by water pressure.

“That’s the horror part of it,” said William Olsen, 72, of York. “They had to know.”

Had he not been attending a training program, Olsen, a crew member, would have been on the submarine when it went down that day, April 10, 1963.

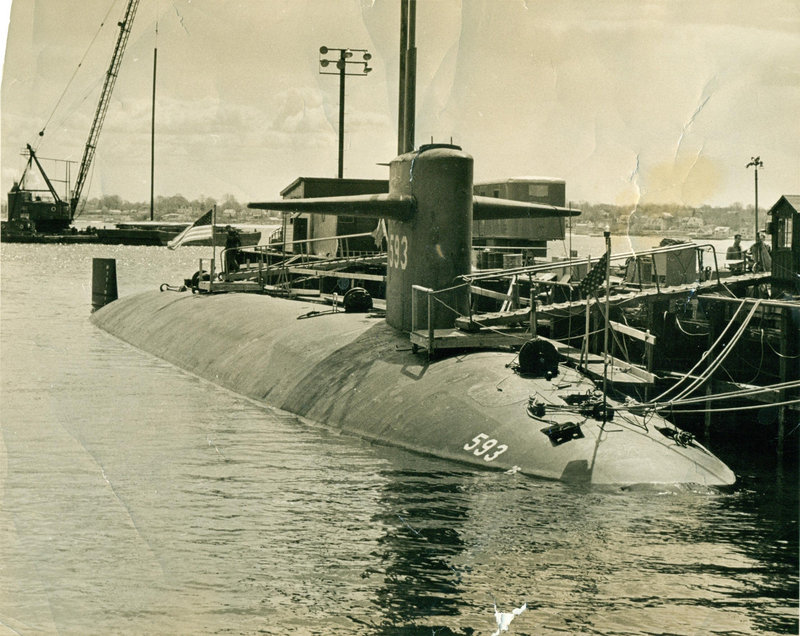

The sinking of the Thresher 50 years ago was a turning point for the Navy. The nation’s newest and most advanced nuclear submarine at the time, the Thresher sank when a weld on a pipe gave way during a test dive 220 miles east of Cape Cod in waters nearly two miles deep.

No one survived. The accident remains the largest loss of life ever on a Navy submarine. After the Thresher sinking, the Navy put much greater emphasis on quality control during the manufacturing of submarines, and developed new safety measures and designs to ensure that a submarine faced with a similar catastrophic flooding would always recover.

Many Americans today are not familiar with the story of the Thresher. But people in Kittery and other communities near the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, where the submarine was built, have never forgotten.

Forty-seven of those lost lived in the area, including 30 sailors, 10 shipyard workers and seven shipyard engineers. The workers and engineers were on board to monitor the submarine’s performance during the tests. In all, 17 civilians were on board the Thresher when it sank.

“It was an absolutely terrible thing,” said Russell Van Billiard, 82, a retired shipyard engineer who helped design the Thresher’s torpedo room. “It was such a close community. Everybody knew somebody who was on it, or knew a number of people who were on it.”

MEMORIALS NEXT WEEKEND

Memorial services are held every year at the Kittery shipyard. But this year – the 50th anniversary of the Thresher’s sinking – the service will be the largest ever.

More than 700 family and crew members and 400 others are expected to attend Saturday’s private memorial service at 1 p.m. in the Portsmouth High School auditorium, the only available venue in the area large enough to hold that many people.

A public ceremony will be held at 9 a.m. Sunday, with the dedication of a new memorial for the Thresher at Kittery’s Memorial Circle on Route 1. The flagpole is 129 feet tall – one foot for each man lost at sea.

Many family members and former crew members have been saving money for years to attend the weekend’s events. Their advanced ages – many are now in their 70s and 80s – has added a sense of urgency to the occasion because they are the last generation to have known the dead.

At the memorial service, there will be large story boards containing photographs and information about individual members of the Thresher crew. Each board will be a gathering place for family members and the retired sailors and shipyard employees who worked with them, said Kevin Galeaz, commander of the Thresher Base United States Submarine Veterans.

“This is the last opportunity to unite the first generation submariners who knew the men personally with the family members, including second-generation children, many of whom don’t remember their fathers,” he said.

It’s critical for the Navy that the younger members remember the Thresher because it reminds them to focus on safety when they work on submarines, said Rear Adm. David Duryea, deputy commander for Undersea Warfare, which oversees the safety programs that were developed after the Thresher disaster.

“It was an event that changed our whole culture in how we build and maintain submarines,” he said. “We strive to make sure that our work force remembers the lessons learned.”

SAYING ‘HELLO’ AGAIN

At a time when military budgets are under pressure, the Navy also uses the Thresher’s story politically, to convince Congress to continue funding its submarine safety initiatives.

For some family members, the political messages at the memorial services are a distraction. For them, the service allows them to be closer to someone they love and haven’t seen for 50 years.

“This isn’t saying ‘goodbye.’ It’s like saying ‘hello’ again,” said Debby Ronnquist, 72, of Kittery, whose husband Julius Francis “Buddy” Marullo, a quartermaster, died on the Thresher, leaving her alone with two children under the age of 3.

Last week, one of Marullo’s friends stopped by her house to show her an old movie of him skiing.

“It’s an incredible feeling to see him like that, vibrant and alive and happy,” she said.

Children of the lost men are eager to soak up new information about their fathers.

For Debby Ronnquist’s daughter, Marcye Philbrook, 52, who was 2 1/2 when the Thresher sank, her deepest connection to her father is a sock she found in a box in storage when she was in her 20s. She was startled to see the imprint of the foot, and that she could smell his odor.

“That’s when I felt he was a real person,” she said.

Suzy Johnson, 69, was 17 when she first met Ed Johnson, chief engineman on the Thresher. He was a fun-loving and dashing sailor, thrilling in his beige Navy uniform. The couple dated for more than two years, despite her mother’s opposition.

Although she would later have two children with two other men, Johnson remains the love of her life, she said.

For days after the Thresher was lost, his love letters to her continued to arrive in the mail.

“Upon opening them I could smell the Thresher, and Ed’s words demanded no reply but were so loving,” she said.

FINAL JOURNEY

Crew member John Riemenschneider, of Lebanon, was not required to join the submarine on its final journey because he had been assigned to another submarine. He had a $2 bet with his best friend, Jack Hudson, that he would not be ordered to go on the Thresher that day. While he was asked to join the Thresher crew, he decided not to, in order to win the bet. It saved his life.

Riemenschneider last spoke to his friend as the submarine departed the shipyard.

“I told Jack I would see him when he came back,” he said.

The Thresher, which was launched in 1961, was the first in its class of a new line of advanced attack submarines. It could travel faster, dive deeper and operate more quietly than any other submarine in the world.

It had been at the Navy yard for several months for repairs. After the work was completed, it left Kittery on the morning of April 9 to conduct a series of post-overhaul trials.

The next morning, as the submarine rescue ship USS Skylark stood by, the Thresher began a deep-diving test.

That was when things went wrong. At more than 600 feet below the surface, seawater probably rushed into the engine room through an opening created when the weld on a pipe gave way, according to a Navy Court of Inquiry. The pipe was used to bring cold water to cool the nuclear reactor.

The reactor automatically shut down when the water shorted out the electrical equipment that controlled it.

The submarine lost propulsion power. The crew’s only chance to save themselves – a blast of high-pressure air to create buoyancy – failed.

The submarine, which had been gliding forward with its bow upward, began descending, stern first, like a stalling airplane.

Monitoring the dive from the surface, the USS Skylark received a mostly garbled transmission saying that the submarine was “exceeding test depth,” the depth at which the submarine could operate safely. One minute later, the Skylark detected a high-energy, low-frequency noise characteristic of a submarine imploding.

The Thresher disintegrated into pieces as it tumbled 8,400 feet to the bottom of the Atlantic.

On the surface, the Skylark continued to try making contact with the Thresher.

Ira Salyers, 80, a crew member on the Skylark, was instructed to throw hand grenades over the side to signal the Thresher to resurface. He said the crew was hoping that the problem was only that the Thresher’s communications system was down.

He said the Skylark conducted a sonar search for several days but never found any sign of the Thresher.

Salyers said he was a tough, hard-drinking sailor and never thought much about the loss. But 12 years later, while attending a church service in Florida, he thought about the men on the Thresher and began to weep uncontrollably.

“All those years later, it hammered me like a ball bat, seeing that all 129 men died when the hull came apart in that cold ocean,” he said.

A Navy investigation after the disaster concluded that deficient shipbuilding and maintenance practices had contributed to the sinking, and that records for critical materials and work accomplished were incomplete or nonexistent.

In response, the Navy developed a program called SUBSAFE. Not only were improvements made in submarine design and manufacturing, but the operations of submarines were limited until the readiness and safety of submarines were independently verified. The Navy has never lost a submarine that has gone through the program.

Olsen, the crew member from York, said all submariners owe their lives to the men who died on the Thresher.

“Family members have every right to be proud,” he said. “These men did not die in vain.”

Tom Bell can be contacted at 791-6369 or at:

tbell@pressherald.com

Twitter: @TomBellPortland

Send questions/comments to the editors.