Gerry Boyle remembers feeling a kick in the gut when he started reading his Morning Sentinel in his driveway the morning of Dec. 18.

A lot of people had a strong reaction to the initial news that Waterville toddler Ayla Reynolds had disappeared from her father’s home, and was reported missing the day before. For Boyle, it was a stunning déjà vu.

Mystery writers are used to being asked where they get their ideas, and as a former reporter and columnist for the Morning Sentinel, Boyle has plenty of ammo.

That December morning, the tables were turned.

“I started checking off the similarities,” he said this week.

His latest book, “Port City Black and White,” had been released two months before the child’s disappearance.

In the opening chapters, a toddler is reported missing. It was a Friday night, the baby had been put to bed while a young parent and some friends hung out. Sometime during the night, the baby disappeared.

The situation was similar, the personalities and ages of some of the characters were similar. As the Ayla Reynolds story unfolded, the parallels to his book continued.

“The initial reaction was the same. The police search, the criticism that police weren’t doing enough,” he said this week over coffee at Jorgensen’s Café in Waterville.

It wasn’t the first time the eerie similarity between a recently released book and a local crime had happened to Boyle.

“Home Body” came out in 2004. In the book, a young woman is stabbed to death under the Veterans Remembrance Bridge in Bangor by a transient named Crow Man.

In August 2009, Holly Boutilier, 19, about the same age as Boyle’s victim, Tammy, was stabbed to death under that same bridge, in the exact same spot. Transient Colin Koehler was later convicted of killing her.

Boyle said this week that both times he “felt a little responsible.”

Obviously, no one involved in either the Ayla case or the Boutilier murder was reading his books and copying him. What he felt went deeper.

“When this happened in my fictional world, I was gaining from this,” he said. “I was inventing stories.”

When it happens in real life “all the sudden it isn’t so much fun.”

“You begin to question at least temporarily why you do this,” he said. “Why do we make up these stories? Why do we enjoy this as a creative outlet, when real life is so horrific?”

He laughed. “Part of you says, ‘Why don’t you write nice books?'”

Boyle is used to criminals, and he has a certain take on them.

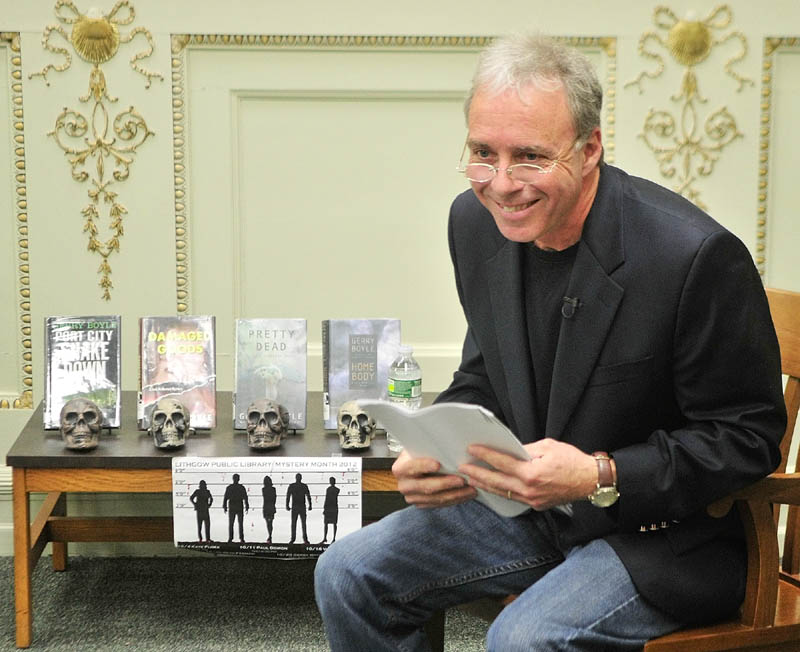

At a reading at Augusta’s Lithgow Library last week, he told the audience that when he was a reporter, first in Rumford, then Waterville, he kind of enjoyed the criminal element. He added that a lot of criminals are regular people who made a bad decision that defined them for life.

He elaborated on that this week.

“What I learned from reporting is that criminals are just as complex as the rest of us,” he said. “Some are very charming, personable, nimble thinkers, survivors.” Others, though, are just bad people.

As a fiction writer, he doesn’t do a lot with drug crimes or serial killers. People who commit crimes because of a drug addiction “are like a rat in a cage,” he said.

“They’re just not interesting to me.”

Same goes for serial killers. “When you can dismiss someone as just being crazy, that’s not very interesting.”

“I try to have all my criminals have some redeeming value, some character, so you want to read about them.”

It has yet to be concluded what the criminal element may be in Ayla’s disappearance.

As a reporter, Boyle felt the idea that a stranger walked into the tiny house on Violette Avenue overnight Dec. 16 and took the 18-month-old Reynolds didn’t make sense.

“The anonymous abduction thing was preposterous right from the beginning,” he said. Even so, when Department of Public Safety spokesman Steve McCausland said early this year that the abduction explanation “didn’t pass the straight face test,” Boyle was surprised.

“I’ve never seen that before,” he said. “They don’t do that lightly.”

Boyle has theories about what happened to Ayla Reynolds. After all, that’s what he does. But he also points out that she may never be found.

She’ll have been missing 11 months on Nov. 17.

And that, ultimately, is why he doesn’t write “nice” books.

“That’s one thing books do,” he said. “They give you closure. That’s the worse case, for the parents of a missing child to die, just not knowing.”

Twice now, he’s written a mystery novel and then watched a real-life version play out. It made him do a lot of thinking about his own responsibility.

“Once you get over the shock, you assess why you write these books at all,” he said.

Both times, rather than stepping back from writing books that center around crime and human tragedy, he came back with more conviction than ever.

“There’s a moral lesson that’s taught,” he said. “And the lesson is not that someone can do this and get away with it.

“In the fictional world a modicum of justice is dealt out. That’s something that’s not necessarily true in the real world.”

“If real life can’t figure this out, let’s create a world in which we can,” he said.

“When you turn that last page, even if the child is not found, at least you know what happened. When you turn that last page, it will be resolved.”

Maureen Milliken is news editor at the Kennebec Journal and Morning Sentinel. She grew up in Augusta. Email her at mmilliken@mainetoday.com. Kennebec Tales appears the first and third Thursday of the month.

Send questions/comments to the editors.