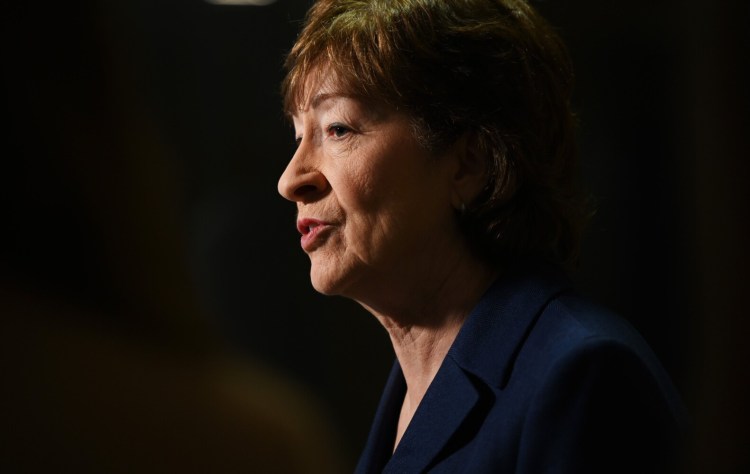

Her closely watched vote on President Trump’s impeachment now part of history, U.S. Sen. Susan Collins can look ahead to her re-election bid for a fifth term this November.

But her decision not to vote for the president’s removal is almost certain to weigh heavily on the campaign, and perhaps, on her legacy as the latest in a long line of centrist Maine politicians.

“As soon as impeachment advanced to the Senate, I don’t think there was any chance of a good outcome for her,” said Mark Brewer, a political scientist at the University of Maine. “This was a classic Susan Collins attempt to navigate a politically tricky issue, something she had done many times traditionally. But what isn’t traditional is how much the political environment has changed around her.”

Neither of Collins’ options was appealing.

She could vote to convict Trump, a man she didn’t vote for and whom she once called “unfit.” Or she could vote to acquit, which would keep Trump’s fervent supporters from going after her.

Collins chose the latter. She criticized the president for demonstrating “very poor judgment” in discussing a possible investigation of former Vice President Biden and his son with the Ukrainian president and for withholding foreign aid but concluded his conduct did not warrant “the extreme step of immediate removal from office.”

Her vote to acquit stood out even more once Utah Sen. Mitt Romney became the only Republican to vote for removal.

For Democrats, many of whom used to support her, it was the latest example of a self-proclaimed moderate not standing up to Trump. Republicans, meanwhile, many of whom don’t feel she’s been conservative enough over the years, are comforted that she’s been loyal when her vote was needed most.

Josh Tardy, a top State House lobbyist and former lawmaker who chaired Collins’ 2014 re-election campaign, said he doesn’t think the senator will be judged on her impeachment vote or any single issue.

“It won’t have the impact people think it might have on this race,” he said. “Most people looked at impeachment as a partisan spectacle. Democrats will try to use it and Republicans will be very happy about the vote. And unenrolled voters are going to make their decision on Susan Collins over the entirety of her career, the way they always have.”

Collins’ speech on the Senate floor Tuesday, a day before Trump was formally acquitted, may not be remembered as much as her interview with CBS News’ Norah O’Donnell the same day. Asked if she’s confident the president won’t seek foreign assistance again, Collins replied, “I believe that the president has learned from this case,” and added later, “I believe that he will be much more cautious in the future.”

Democrats seized on those comments immediately as naïve, given that Trump has never taken any responsibility. In fact, only a couple of hours later, The Washington Post reported that Trump was asked about Collins’ comment that he had learned his lesson. Trump said he did not agree and that he had done nothing wrong.

Collins soon walked her comments back in interviews on Wednesday.

“Well, I may not be correct on that,” she told Fox News’ Martha MacCallum when asked about why she thinks Trump may have learned his lesson. “It’s more aspirational on my part.”

On Friday, appearing in Maine for the first time since the vote, Collins stressed that her vote was not based on whether she likes or dislikes the president or whether she supports or opposes his policies.

“This was a vote on the evidence presented by the House,” she said. “Of whether they met the very high bar of bribery, treason, high crimes and misdemeanors that is set forth in the constitution.”

‘TOUGHEST RE-ELECTION FIGHT’

Collins was first elected to the U.S. Senate in 1996, two years after she narrowly lost a three-way race for governor in Maine. She was victorious among eight Republican primary contenders, but then finished third behind Democrat Joseph Brennan and independent Angus King, who served two terms as Maine’s governor and is now Collins’ colleague in the Senate.

Collins has been re-elected to the Senate three times so far, and in each race, she has increased her margin of victory over the Democratic challenger – Chellie Pingree in 2002, Tom Allen in 2008 and Shenna Bellows in 2014.

Most observers expect that trend to end.

“This will undoubtedly be the toughest re-election fight she’s ever faced,” said Brewer.

Michael Franz, professor of government at Bowdoin College, said the impeachment vote was an encapsulation of how tricky it can be for Republicans to navigate in the Trump era.

“It’s a unique political environment in that every decision is either for or against Trump, and that carries a huge set of consequences for Republicans,” he said. “Collins has crafted an image and a political identity that she sees as critically important to the center, but that’s largely gone.”

There hasn’t been any public polling yet in the 2020 Senate race, but at least one well-respected poll shows Collins’ long-held popularity has taken a major hit in the Trump era.

Morning Consult, which conducts quarterly surveys of every senator’s performance, released a poll last month that showed Collins as the least popular senator in the country, below even the polarizing Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell. Of those surveyed, 42 percent approved of her performance while 52 percent did not.

Those numbers have fallen since Morning Consult’s survey from last summer, which showed Collins’ approval rating at 45 percent and McConnell’s disapproval at 48 percent. Her approval rating dropped 16 points between the first and second quarters of 2019, which was the most of any senator in the survey.

Sara Gideon, Maine’s House speaker, is widely viewed as the Democratic primary front-runner and is backed by national Democratic groups, but she still faces a challenge from lobbyist Betsy Sweet, former Google executive Ross LaJeunesse and attorney Bre Kidman.

Brewer, the UMaine political scientist, said one thing that Collins has going for her is her likely opponent, Gideon, who he said doesn’t fit the mold of candidates who typically do well in statewide races.

“With the exception of (former Gov. Paul) LePage, we don’t have Trump-style Republicans in Maine, and Democrats who won statewide in recent years are more moderate,” he said. “My take would be different if (Collins) were running against a Jared Golden or Mike Michaud-style Democrat, or someone like (Secretary of State) Matt Dunlap.”

‘POLITICS HAVE CHANGED’

On impeachment, there was never a chance that enough Republican senators would vote to remove the president, but Collins was among a small group seen as possible defectors.

Collins did vote for witnesses but was joined by only one other Republican, Romney, and her vote didn’t matter. Critics have pointed this out as another example of Collins bucking her party only when the outcome has been decided. Others have suggested McConnell gave Collins a “hall pass,” a characterization she has bristled at.

Back in 1999, Collins also voted to acquit President Bill Clinton during his impeachment trial, joining nine other Republicans and all 45 Democrats on one article and four other Republicans and every Democrat on the second.

Kevin Raye, former Maine Senate president and ex-chief of staff to Republican U.S. Sen Olympia Snowe, said he didn’t know how Collins would vote but wouldn’t have been surprised with either choice.

“Much like she did in 1999, she took the impartial juror thing seriously,” Raye said. “And Republicans were furious that she voted to acquit (Clinton) then, just as Democrats are furious now.”

“She hasn’t changed, politics have changed,” he continued. “But I think that means we need her more than ever.”

Romney was the lone Republican who voted to convict Trump and remove him from office. He is the only senator in America history to vote to remove a president of his own party in a Senate impeachment trial.

“Corrupting an election to keep oneself in office is perhaps the most abusive and destructive violation of one’s oath of office I can imagine,” the former presidential candidate said.

It took almost no time for Republicans to castigate Romney for his vote, which was seen as a betrayal. That is almost certainly what Collins might have faced had she joined Romney.

“I respect his decision,” Collins said of Romney. “I’m not critical of it but I disagree with it and reached a different conclusion.”

Instead, she’ll face protests from Democrats and progressives the same way she did in 2018 after her vote to confirm Trump’s controversial U.S. Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh and, a year earlier, when she supported Trump’s tax cut bill.

Collins has acknowledged that her vote would be unpopular with some Maine voters.

Some national opinion columnists have been especially critical of Collins since her vote, in large part because she was one of a small number of Republicans thought to be considering voting to convict.

A piece in the lifestyle magazine GQ last week, headlined “Why Susan Collins Is More Dangerous Than Mitch McConnell,” began, “In the era of Trumpian hyper-partisanship, Susan Collins, the ‘moderate’ Republican senator from Maine, seems to get her kicks from positioning herself as a potential swing vote in the most dramatic political moments and then delivering crushing blows of disappointment to Democrats.”

Longtime New York Times columnist Gail Collins (no relation) wrote that Susan Collins had the “worst impeachment moment” when she said Trump had learned his lesson.

Brewer called the comment “an avoidable error.”

“If I’m Gideon, I make more hay out of that than her vote to acquit,” he said. “I don’t know anyone who thinks this is going to change Donald Trump one iota. That idea is something that most people would find implausible at best and maybe ridiculous at worst.”

Tardy, who spoke before Collins amended those comments, said his impression was that Collins meant that despite the president’s confidence throughout this inquiry, “I don’t think he wants to go through this again.”

But Collins was cleaning up her comments less than 24 hours after she made them.

“The call was wrong. Parts of the call were fine,” she told Fox News’ MacCallum on Wednesday, adding that he “should not” have asked for a foreign government to investigate a rival. “He should not have done that. And I hope he would not do it again.”

FUNDRAISING APPEAL

Collins has said her re-election bid had nothing to do with her decision on impeachment and she has the reputation of someone who makes her decisions independently.

However, her campaign sent out a fundraising appeal hours after the impeachment vote highlighting her decision to acquit. She characterized the origins of the impeachment hearings as partisan and concluded the House managers “failed to prove their case.” She did mention that she thought Trump acted inappropriately.

“The criticism from my political opponents has been swift and harsh,” the email to supporters read. “Part of that might just be that they are mad that I refused to give into their attempts to pressure me.”

That language plays to the Republican Party base but likely not independents.

“I sort of wonder if her vote, especially given Mitt Romney’s vote, will hurt her more than if she voted to convict,” said Franz, the Bowdoin professor. “Romney took a bold step that could make it harder for Collins. It she voted with him, it might have inoculated her from criticism from voters in Maine who have stuck with her even though they might be more liberal. Her seat is so critical to Republicans in the Senate, so those voters won’t risk losing the seat.”

Franz said the consensus seems to be that congressional Republicans simply don’t want to incur Trump’s wrath. He said the real test could be if Trump decides he wants to campaign in Maine, as he did four years ago. Would Collins appear with him?

Tardy, though, downplayed the notion that voters’ feelings about Trump would bleed into the Senate election.

“It’s important that the president endorse her, and he has. She’s doing well with the Republican base,” he said, before adding that he doesn’t think the race will be a referendum on Trump.

Added Raye, the former Maine Senate president: “If you go back and look, every time she’s been up the prediction has been that she’s in trouble this time. She has had major opposition before. If anyone can navigate that, it’s her.”

The 2020 election is still months away and a lot can, and likely will, happen before then. Still, Collins’ legacy, whether she likes it or not, is inexorably tied to Trump. Her votes never generated this level of scrutiny before.

Brewer said how the impeachment vote fits into her legacy is harder to answer. But he pointed out that Collins’ political mentor, former Republican U.S. Sen. William Cohen, has said Trump’s conduct was impeachable. Cohen, when he was a U.S. House member, was one of the first to break with Republicans during the impeachment battle of President Richard Nixon, who resigned before any votes took place.

“History will decide what this vote means for individual senators’ legacies,” Franz said. “From a purely political perspective, a vote to convict would perhaps have had some legacy solidification that might not be there now.”

Tardy sees it differently.

“There are a lot of her votes that she can be judged on. She’s never missed a roll call,” he said. “I don’t think one issue or one vote is going to define Susan Collins.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.