To the yearbook editors at the all-girl Kingswood School, Ann Lois Davies’ destiny seemed pretty obvious.

“The first lady,” the entry beside the stunning blonde beauty’s photo in the 1967 edition of “Woodwinds” concluded. “Quiet and soft spoken.”

The modern feminist movement was just dawning, and even some of the girls at the staid prep school in the wealthy Detroit suburb of Bloomfield Hills were feeling their oats — if in a somewhat tame way. Charlon McMath Hibbard remembers getting a doctor’s note about her feet, so she wouldn’t have to wear the obligatory saddle Oxfords.

“We were a rather outspoken class,” says Hibbard, who took weaving, and played lacrosse and basketball with the future Ann Romney. “We were just not going to take the status quo.”

But considering that their classmate was already betrothed to Willard Mitt Romney — the dashing son of Michigan governor and Republican presidential contender George W. Romney — the “Woodwinds” staff weren’t exactly going out on a limb.

Having been first lady of Massachusetts, Ann Romney has already lived up to those yearbook expectations. Now, she’s in the running for the national title.

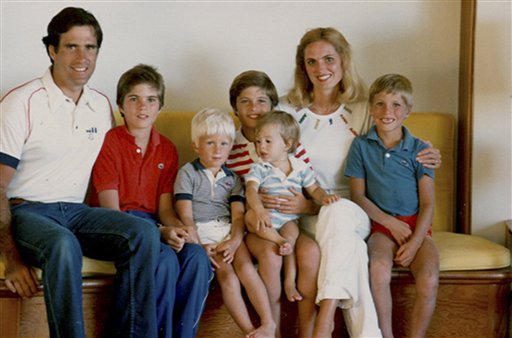

The 63-year-old mother of five and grandmother of 18 has embraced the homemaker image that Hillary Rodham Clinton so openly scorned. On the campaign trail, she’s been filmed baking pies and serving her grandmother’s Welsh skillet cakes on the media bus. But while Ann Romney is more Betty Crocker than Betty Ford, it’s clear she’s not going to be Mitt Romney’s silent partner. In fact, it was she who divulged that women were on the short list of possible vice presidential picks.

Critics have painted her as the dutiful, starry-eyed wife, standing by — and behind — her man. Friends say that’s an over-simplification.

“With Mitt, it’s always going to be ‘we,'” says Pamela Hayes Peterson, who has known Ann Romney since the sixth grade and was one of her bridesmaids. “She is NOT subordinate, trust me. Did she want to be in the public eye? Probably not. She is so gracious and she loves him so much that, if it’s important to him, she will come outside of her comfort zone to be where she needs to be for him. But he will do the same thing for her.

“We’re talking about the most unusual couple in the world,” she says. “And the public doesn’t see this.”

GETTING CREDIT

Three years ago, when Romney’s official gubernatorial portrait was unveiled at the Massachusetts Statehouse, it included something unprecedented: A small photo of the state’s first lady, smiling from the desk. There was some carping in the arts community, but Romney insisted.

“I gather that he credits her for much of his success,” says New Hampshire artist Richard Whitney, who worked from Romney’s favorite photo of Ann. “He basically told them he was paying for the portrait, and that’s what he wanted. I was very impressed with that.”

They have been through a lot together. They’ve built a large family, and a fortune. But there have been hard times — Ann’s multiple sclerosis and breast cancer; a stillborn child; the rigors of campaigns, some successful, more of them not. Stung by her portrayal as a “Stepford Wife” in her husband’s losing 1994 run for the U.S. Senate, Mrs. Romney famously declared: “You couldn’t pay me to do this again.”

And yet, she has — in 2002, 2008 and now a third time.

It means again opening herself up to uncomfortable scrutiny and sniggers about the couple’s wealth, estimated to be in the $250 million range.

Like her husband, Ann Romney sometimes seems oblivious about her life of privilege. Mitt mentions that Ann “drives a couple of Cadillacs.” She shows up in a $990 designer shirt for a TV interview, and in another says the Romneys won’t release more of their tax returns because “we’ve given all you people need to know.”

Co-owning a pricey horse that high-stepped through Olympic dressage doesn’t help. Comedian Stephen Colbert had so much fun with that one that he declared “horse ballet” his official Sport of the Summer: “So kids, run out and get yourselves a $100,000 Hanoverian.”

ALWAYS BY MITT’S SIDE

If Mitt is there, Ann is with him.

It has been that way for 47 years, since Mitt Romney — an 18-year-old student at the all-boys Cranbrook School — walked into a party and saw the nearly 16-year-old Ann, who attended Cranbrook’s sister school, Kingswood.

For him, the moment was nothing short of electric.

“I caught his eye, and he never let me go,” Ann told the Boston Globe in a 1994 interview. “I mean, he hotly pursued me.”

The girl he set his heart on was the middle child and only daughter of Lois and Edward Roderick Davies. The immigrant son of a Welsh coal miner, Davies — an engineer and inventor — founded Jered Industries, a maritime equipment manufacturer that has since branched out into naval weapons handling and delivery systems. He also served as mayor of Bloomfield Hills.

Her mother was a cosmetics sales representative who was well into what she thought would be a lifelong career when she married Davies at age 30. After that, she became the dedicated housewife and mother that friends say would serve as Ann’s model.

Ann was, in her own words, a tomboy, “playing baseball and football with the boys, and catching frogs and hunting for snakes out behind the house.”

At Kingswood, she built a resume that any career-minded woman would have envied. In addition to playing field hockey, basketball and lacrosse, she reported for the student newspaper, the Clarion, volunteered at Pontiac State Hospital, served as a student adviser and was on the student council. She won a regional award for her weaving and also acted in several plays, including “Boeing My Way” and “Solomon and the Balkis.”

“She had lots of depth,” says Sue Brethen Lapelle, a boarding student who has fond memories of weekends at the Davies home and swimming in their pool.

And now, she had Mitt.

“They were so cute together and so happy together,” says Lapelle, an Atlanta interior designer who had briefly dated Romney. “There was never one ounce of any question that they weren’t supposed to be together, I guess.”

Romney proposed to Ann at his senior prom, and she accepted. According to Ann, it was she who initiated her conversion to Mormonism.

Edward Davies had been brought up in the Welsh Congregational tradition; his wife described their family as Episcopalian. In truth, Davies wasn’t much for organized religion.

But his daughter had been quietly searching for a spiritual home. While Mitt was away at Stanford University in California, Edward Davies agreed to allow George Romney to send some missionaries from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to speak with his daughter.

When she was baptized, Gov. Romney officiated.

In 1967, Ann entered Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah. By then, Mitt Romney had suspended his studies to fulfill his missionary duties in France, and she saw him there during a semester abroad in the mountains just southeast of Grenoble — site of the Winter Olympics.

Donlu Thayer was, by her own estimation, a “nerdy, booky person” who always seemed older than her years. Ann, by contrast, was a “bubbly, beautiful thing.”

One weekend, when everyone else was running off to go skiing or shopping, Thayer decided to visit Soeur Macaire, an elderly shut-in from the local Mormon congregation. To her surprise, Ann — then a freshman — offered to go with her to the dingy little apartment.

To her, that was “the essence of Ann.”

“She could have been doing ANYTHING else, and she came with me to see that woman — and nobody else did,” says Thayer, who went on to teach two of the Romneys’ sons at Brigham Young. “Bottom line is Ann Romney is the kind of woman I would instinctively HATE. And I love her.”

PASTA, TUNA & LESSONS

After her return to BYU, Ann briefly dated another student — and even wrote Mitt what the Washington Post characterized as a “Dear John” letter. It didn’t stick.

On March 21, 1969, the couple were married in a civil ceremony at the Davies home. Among the 300 guests attending the reception at the Bloomfield Hills Country Club were the presidents of Ford Motor Co. and General Motors Corp., and then-Rep. Gerald R. Ford.

The following day, the Romneys flew to Utah for a formal “sealing” ceremony at the grand Salt Lake Temple. After a honeymoon in Hawaii, the newlyweds set up house in Provo, where Mitt had enrolled at BYU.

The two children of privilege rented a $62-a-month basement apartment with glued-together carpet remnants covering the cement floor.

“They were not easy years,” she said. “Mitt and I walked to class together, shared housekeeping, had a lot of pasta and tuna fish and learned hard lessons.”

The young family lived off the proceeds from the sale of American Motors shares — purchased with Mitt’s birthday money by his father. Critics would scoff at this self-imposed austerity, but Ann Romney said the couple were determined to make their own way.

“The funny thing is that I never expected help,” she told the Globe. “My father had become wealthy through hard work, as did Mitt’s father, but I never expected our parents to take care of us.”

The couple’s first son, Taggart, was born there in 1970.

After Mitt graduated from BYU in 1971, the couple moved to the wealthy Boston suburb of Belmont so he could attend Harvard. Ann took night classes through Harvard’s Extension School and completed her BYU bachelor’s degree, with a concentration in French, in 1975.

After Tagg, the babies came at fairly regular intervals: Matt in 1971, Josh four years later, Ben in 1978 and Craig in 1981. In between Ben and Craig, Ann Romney lost a child several months into her pregnancy. It, too, was a boy, a source close to Mrs. Romney confirmed. The couple have never spoken publicly about their loss.

It might surprise many people to learn that Ann Romney entered politics long before her husband did.

In April 1977, she was elected to a one-year term representing Precinct 8 on the Belmont town meeting. Among the big issues, says fellow member Maryann Scali: Should the town build a high school?

“She went around and rang every doorbell and got elected,” says Scali, now in her 43rd year as a meeting member. “Who could NOT vote for a person like Ann? She was young and beautiful and energetic and enthusiastic and everything a voter wants in a person to represent them.”

Records show that Romney had perfect attendance. When her term was up, she went back to the job that has come to define her — mother.

She makes no apologies for that. This year, Democratic commentator Hilary Rosen set off a clamor when she suggested that Ann Romney was unfit to comment on economic matters because she “never worked a day in her life.” Ann Romney, in her first-ever tweet, responded by saying: “I made a choice to stay home and raise five boys. Believe me, it was hard work.”

More than a decade would pass before her husband would seek office, but Mrs. Romney played a central role in his decision, too.

In 1992, Edward Davies was staying with the Romneys while undergoing treatment for the prostate cancer that would soon kill him. One day, while Ann was putting away dishes in the kitchen, he grabbed her.

“He said, ‘Ann, you’ve got so much living to do. Think of the exciting things that will happen in the world. I’m so jealous of all the wonders you’re going to see in your lifetime,'” she told a reporter. She said her father’s words “made me realize that, well, I don’t want to look at my life 30 years from now and say, ‘Gee, I wish I’d done that.’ I don’t want to have regrets. I don’t want to say, ‘I’m sorry we didn’t try this or that.'”

A few days later, she told her husband he should run against Sen. Edward M. Kennedy. He lost by 17 points.

MS DIAGNOSIS

Ann Romney threw herself into charity work. She volunteered as an instructor at Boston’s Mother Caroline Academy for middle-school girls. She was also a director of Best Friends Foundation, a program aimed at encouraging inner-city girls to abstain from sex, drugs and alcohol.

In late 1997, Ann Romney felt numbness in her right leg, followed by chronic fatigue and other debilitating symptoms.

“I could hardly walk,” she told a crowd in Iowa last December. “And I couldn’t get out of bed.”

Shortly before Thanksgiving 1998, an MRI revealed that she had multiple sclerosis, an autoimmune disease that affects the central nervous system.

She became despondent, “thinking that my life was over,” she told the Iowa crowd. “That this was the way I was going to always be, and that I was really feeling pretty sorry for myself.”

It was, as she called it, “my darkest hour.” But it also reaffirmed her husband’s commitment to her.

“What he did was say, ‘Look. This isn’t fatal. We’re gonna be OK. I don’t care that you can’t make dinner every night. It doesn’t matter to me. I can eat peanut butter sandwiches and cold cereal for the rest of my life. As long as we’re together, we can handle everything.’ And that gave me, honestly, the permission just to be sick for a while, and just to accept the fact that I had to learn how to deal with this. It was a great time in my life where I had a lot of self-reflection and starting to think what was most important in life.”

In February 1999, Mitt Romney agreed to serve as president and CEO of the foundering organizing committee for the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City. The couple moved to Park City, Utah, where Ann Romney rediscovered horseback riding — a “joy therapy” that she credits with restoring her health, along with acupuncture, reflexology and other holistic measures.

The theme for that year’s torch relay was personal heroes. Mitt Romney selected his wife as his. Cindy Gillespie, who was in charge of the relay and later served Romney as a top gubernatorial aide in Massachusetts, says Ann Romney practiced with props to prepare for her one-fifth-of-a-mile leg.

In his 2007 book, “Turnaround,” Mitt Romney described the emotion of jogging alongside her. “There was the love of my life running the Olympic torch down the street. We had wondered if she would be in a wheelchair by that time. Among my children and me, there was not a dry eye.”

Following the Olympics, Mitt Romney announced his bid for Massachusetts governor. His wife largely avoided media interviews, but was active behind the scenes. After he took office, Romney appointed Ann as his unpaid liaison to the White House Office of Faith-Based and Community Initiatives.

Despite her earlier protestations, when Mitt Romney announced his first presidential bid in 2007, his wife was fully on board. She even had her own website, complete with family recipes. It was a lost cause; Romney dropped out of the race in February 2008 despite winning 11 primaries and caucuses.

Later that year, Mrs. Romney was diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ, a noninvasive type of breast cancer; she underwent a lumpectomy and is reported to be cancer-free.

Ann Romney has said she begged her husband not to run again. So when Lapelle saw her old prep school friend this past April at a 63rd birthday party and fundraiser, thrown by Donald and Melania Trump at their at their 32,000-square-foot triplex on New York’s Fifth Avenue, Lapelle asked her friend why she would put herself through something like that again.

When Mitt said he wanted to try again, Lapelle recalls Ann saying her first reaction was, “Are you kidding me?” But after some thought, Ann asked him to answer one question: “Can you fix the economy?”

“And he looked her in the eye and said, ‘Yeah,'” Lapelle says her friend told her. “And so she said to him, ‘I’m on your team.'”

Send questions/comments to the editors.