Every winter, a sheet of ice covers the bottom of our driveway. By “driveway,” I mean the gravel roadway roughly 10 feet wide that bends for one-tenth of a mile down from the road then up to our backyard and may be suitable for use in Olympic luge events. The spot where it crosses the brook is similar to a gravel railroad causeway and too narrow and dangerous for sledding. We drive cars there, though. You have to watch your speed.

By “bottom,” I mean the flat, shaded expanse just the house side of the causeway where water comes to rest and freezes solid. This ice at the bottom is believed to be a remnant of the Laurentide Ice Sheet, a glacier that covered Maine, Quebec, New York and who knows where else about 25,000 years ago. To find out if it really is a glacier, a certifiable backyard naturalist (me) collects and analyzes data pertaining to the formation, longevity and potential futures of glaciation, particularly in Troy, Maine. This research seems to resume around this time every year.

Does the Troy Driveway Ice Sheet meet the definition of a glacier? Apparently. A glacier, according to the Extreme Ice Survey, is a mass of ice that originates on land. It is usually larger than 100 square feet. It forms from snow falling in layers; the upper layers of snow compress the lower layers into ice.

These are exactly the conditions at the bottom of the driveway. In November or December, snow falls. If it’s sufficiently cold – and I’m not sure whether you’ve noticed it or not, but this winter it has been sufficiently cold not only to maintain ice but to freeze your teeth – then that snow, under the influence of the so-called wheel-rut factor (which speeds up compression of the snow and causes surface crystals to melt and glaze), soon turns into ice. When it snows again, that second layer covers and presumably compresses the first layer; the third covers the second, and so on. Over the 10,000 to 20,000 years that elapse between December and March, an ice sheet 2 to 5 inches thick forms on the bottom of the driveway. Sometimes a notion crosses my mind that it’s suitable for skating, but that’s off the track.

Extreme Ice Survey also says a glacier is a “year-round mass of ice.” Now, by February, it is never remembered for sure whether the ice on the driveway ever wasn’t there. It does not seem like it. It seems like it has been there since the beginning of time. Lacking evidence of any such season as “summer” other than in remote legend, it is assumed that winter here is for all intents and purposes perpetual. If so, then the Troy Driveway Ice Sheet is a year-round mass of ice.

There are two kinds of glacier: Alpine, or mountain glaciers, such as those in Alaska, the Alps and Mount Kilimanjaro; and continental ice sheets, such as those in Antarctica and Greenland. The Troy Driveway Ice Sheet appears to be a mountain glacier because it is somewhat smaller than a polar ice cap and because it appears to flow down the hill and carve valleys in the driveway that appear first in March, proceed well into March proper, continue in March, and go on into that period of March when the mud-freeze-mud-freeze cycle, on top of 10,000 years of winter, makes you think you can’t really take it anymore.

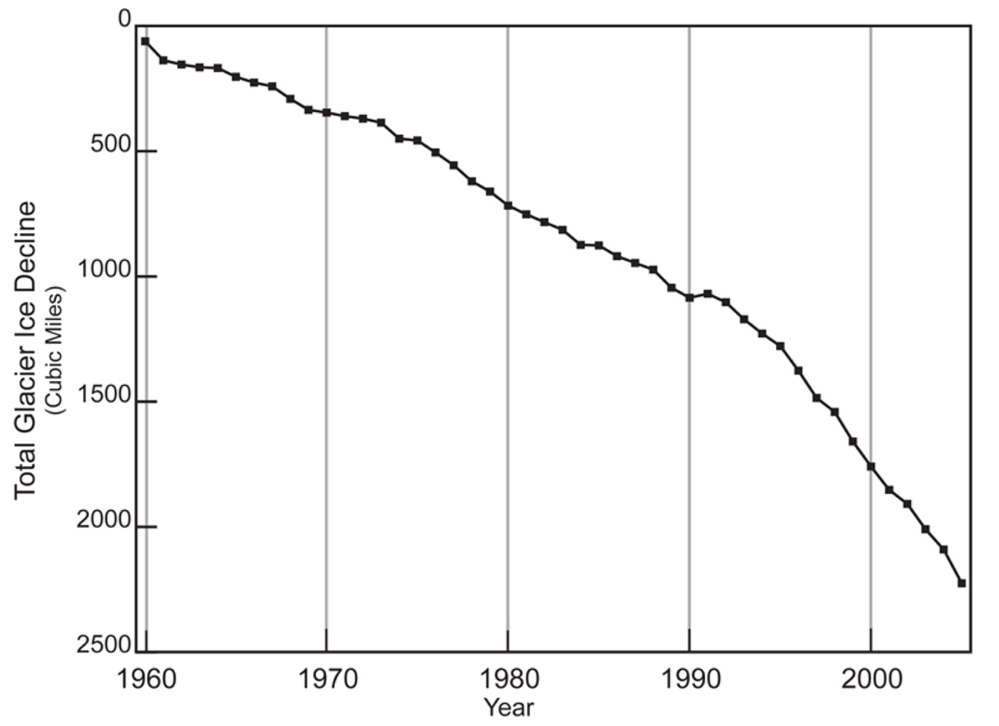

Good news, though. The Troy Driveway Ice Sheet may disappear. Mountain glaciers worldwide have shrunk markedly in the last 30 years, and climatologists predict that at the current rate, they will all be gone within 100 years. Calving – the breaking off of big chunks of ice at glacier outflow areas – has speeded up. Slabs of ice much larger than any previously known have broken off recently, including one twice the size of Manhattan that fell off Greenland’s Petermann Glacier in July 2012.

The melting responsible for disappearing ice is caused by climate change, aka global warming, which is actually happening regardless of how cold it was at your house last night. In the last 10 years, temperatures have risen about 5 degrees Fahrenheit on the Greenland ice sheet. The warming might be part of a long-term climate cycle, but it is almost certainly influenced by a steep rise in carbon dioxide levels unknown in the last half-million years. Corresponding to the steep rise is the fact that at the same time, humans have been pouring carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere at high rates. It is practically certain the three kinds of rise are linked.

This might all be at worst a shrug – so what? – or at best a chance to make a pot of money, which is the way Gov. Paul LePage, ever the optimist, sees it. The trouble is, there’s trouble ahead and trouble behind. If the glaciers keep melting, within 100 years sea level will rise by about 3 feet. Worldwide, about 100 million people live within 3 feet of sea level. One hundred years is headed like a freight train straight at you, me and everybody else, whether we turn two good eyes toward it or not. If in some future future all the glaciers melt, then sea level will rise 200 feet. Meanwhile, mountain glaciers are melting now. A billion people in Asia alone depend on Himalayan glaciers for water. When their drinking water runs dry and their homes are under the ocean, what will happen?

Take my advice, you’re better off not thinking about it. Here in the woods of Troy, the key environmental question is not how billions of people in Europe and Asia will get drinking water, but if or when the ice sheet is going to melt. Those are just two completely different things. That and driving the car over the brook, and along the ice. When you come around the bend, you know it’s the end.

Dana Wilde lives in Troy. His writings on the Maine woods are collected in “The Other End of the Driveway,” available from Booklocker.com and online book sellers. Backyard Naturalist appears the second and fourth Thursdays each month. You can contact him at naturalist@dwildepress.net.

Send questions/comments to the editors.