The plaintiffs in the labor mural lawsuit are appealing the ruling of a federal judge who found that Gov. Paul LePage was within his government speech rights when he ordered the work removed from a state office building.

The plaintiffs contend that U.S. District Judge John Woodcock Jr. was wrong when he concluded last month that the mural was government speech rather than the speech of the artist, as they had argued unsuccessfully. The plaintiffs — a group of two union officials and three artists — will revisit their argument and address points in Woodcock’s decision before a three-judge panel of the 1st Circuit Court of Appeals in Boston.

Jeffrey Neil Young, a lawyer for the plaintiffs, said the case must be sent back to U.S. District Court for a trial because there are a number of factors that a viewer could consider in determining whether the mural was the speech of the government or of the artist. He said the relevant area of the law — the government speech doctrine — is relatively recent and bears fleshing out.

“Judge Woodcock’s decision, in my view, takes a very broad view of the government speech doctrine,” Young said Tuesday. “It’s almost as if anything the government puts up the government can take down. I think that’s way too broad a view of the government speech doctrine.”

LePage spokeswoman Adrienne Bennett called the lawsuit frivolous and politically motivated and said the appeal does not change that.

“This is another way for the opposition to drag out the process, but when all is said and done, we believe that we will prevail in this case. It would be stunning if government officials were barred from making decisions about what artwork can hang in public buildings,” she wrote in an email.

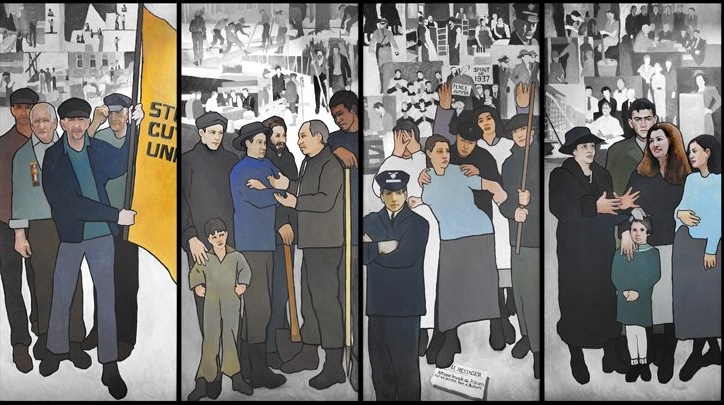

At the center of the lawsuit and the associated controversy is a mural that was commissioned in 2008 by the administration of Gov. John Baldacci. The artist, Judy Taylor of Tremont, was directed to created a mural that showed the “value and dignity of workers and their critical role in creating the wealth of the state and nation.” She created an 11-panel work that depicts scenes from Maine labor history, including a shoe-worker strike, child laborers and Rosie the Riveter. The work cost $60,000, mostly federal dollars.

The mural hung in the waiting area of the Department of Labor in Augusta. LePage decided to have it removed after receiving an anonymous complaint that said the work amounted to union propaganda. The governor later said that he objected not to the content but the use of money from the unemployment insurance fund.

LePage’s decision prompted hundreds to protest outside the Labor Department offices. The mural was removed over a weekend and is being kept in an undisclosed location.

The plaintiffs sued LePage and other state officials to have them return the mural, reveal its location and make sure it is in good condition.

The timetable for the appeal has not yet been set. The plaintiffs filed their notice of appeal last week, but no briefs have been submitted.

Calls seeking comment from representatives of the attorney general, whose office argued on behalf of the state in the suit, were not returned Tuesday.

Deputy Attorney General Paul Stern has previously argued that the mural is clearly government speech, given that it was the state that hired the artist, paid for the work and directed its content.

Young said Tuesday that an individual who walked into the Labor Department waiting area before the mural’s removal would have seen the mural, a pamphlet that described how Taylor created it and an old framed political pamphlet opposed to minimum wage laws. He said the viewer would understand that both the mural and the pamphlet were not representing the viewpoint of the state but those of their creators.

Young differentiated between places like public parks and government buildings. The former have traditionally served as forums for the display of monuments and other works that represent a government viewpoint while the latter may contain arts of different types, typically less permanent than a two-ton statue in a public park. He said public familiarity with the state’s public art program also makes it less likely viewers would associate a picture with government speech.

Send questions/comments to the editors.