Mike Seamans considers that he might be single for a long time.

“I won’t buy a girl a diamond,” the Morning Sentinel photographer said after a summer excursion to Sierra Leone with Greg Campbell, author of “Blood Diamonds: Tracing the Deadly Path of the World’s Most Precious Stones.”

Campbell’s book described the Revolutionary United Front rebels’ torture, rape and maiming of thousands of civilians and children — hacking off limbs with machetes was their signature — during the country’s brutal 1992-2002 civil war.

The rebels’ control of diamond mines helped fund their fight against the government.

Campbell originally went to Sierra Leone in 2001 to report for the San Francisco Chronicle and do research for his book, which was the inspiration of the 2006 film “Blood Diamond” starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Jennifer Connelly.

This summer, Campbell returned to see what conditions were like in the aftermath of the civil war, and to see if the process established to certify that diamond purchases were not financing wars and human rights abuses is working. Campbell plans to re-release “Blood Diamonds” in 2012, with two new chapters.

Seamans, 36, of Sidney, is a 1994 graduate of Edward Little High School in Auburn. He once worked at the daily newspaper, Fort Collins Coloradoan, and befriended Campbell, 41, in Colorado.

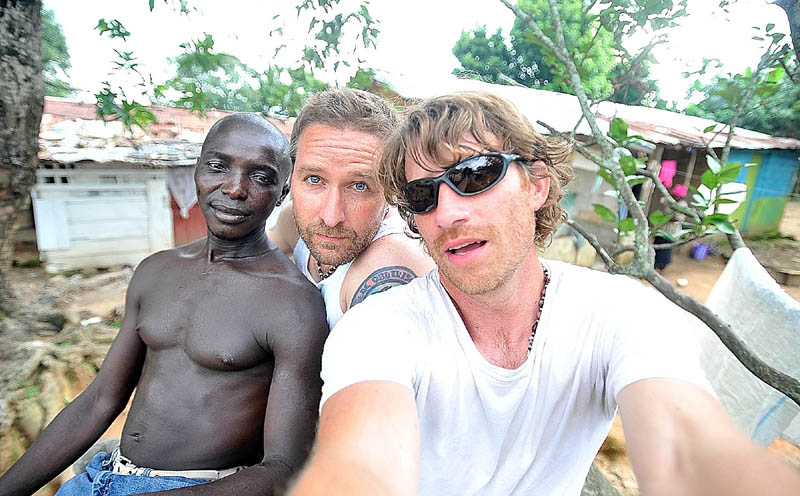

Seamans accompanied the author to photograph daily life in Sierra Leone. The two plan to pitch in-depth stories and photographs from their trip to news outlets and magazines.

Seamans said Campbell’s impression was that average citizens in Sierra Leone still have the same sense of desperation that they did 10 years ago. The only things missing this time, he said, were the bombs and bullets.

“They’re still living in squalor,” Seamans said. “In Sierra Leone, you’re lucky if you can find a hotel with power and running water at the same time.”

Or a hospital.

During the trip, their fixer — a man named Jango with numerous contacts who worked as their guide — contracted malaria.

“The people in Sierra Leone get malaria like we get the flu,” Seamans said.

The three traveled to a hospital in Koidu, which had no power or running water, so Jango could be treated for the mosquito-borne infectious disease.

A few days later, at that same hospital, Seamans photographed a 33-year-old woman undergoing a hysterectomy.

Because there were no lights, Seamans said the surgery was performed next to a window with a broken screen. A plastic tarp with stains from a previous operation covered the operating table.

Seamans said the doctor poked at the patient with forceps to see if the general anesthetic had taken effect.

Sierra Leone, which has a population of about 5.2 million, has been listed by the United Nations as among the world’s least livable countries because of its civil wars, sexual slavery, torture, conscription of child soldiers and cannibalism. The average life expectancy there is 48 years.

“The whole population is so beat down and worn out,” said Seamans. “There are no visible changes being made to help their people.”

Children are lucky if they get to go to school, Seamans said.

He saw barefoot children as young as 3 in a quarry pounding rocks into gravel for construction companies in 90-plus degree heat.

Seamans said another distinguishing feature of Sierra Leone, besides the poverty, is “corruption, corruption, corruption.”

Everybody— beggars and officials — are on the take.

“You can’t do anything without first paying somebody off,” he said. “It’s so ingrained in the culture. The political system seems broken. The corruption is the biggest hurdle. It needs to be removed from the equation.”

He recalled arriving with crisp $20 bills and blowing through $120 in tips and bribes the first night. Quite an amount considering many people there live on $2 a day, he said.

Seamans said he paid a police officer toting an automatic weapon for access to an ATM, then paid the officer again after withdrawing money.

And even without bullets and bombs, Seamans said he was in a near-constant state of alert because of stress during the 21-day trip.

“My mind was always running,” he said, “I was constantly vigilant and looking for who was around me and what I had with me.”

Lakka, a fishing village near Freetown, turned out to be an oasis from the daily strain and peddlers.

Seamans said the beach — with thatched huts, reggae music and fresh barracuda — provided an incredible reprieve. “It was the most relaxed I’ve ever been in my life,” Seamans said. “It was like a Corona commercial.”

Every couple of days, Seamans and Campbell changed hotels to avoid the attention of thieves.

To get to diamond mines and other sites, they boarded ferries, taxis, buses and dirt bikes — and in a country with rickety vehicles, rough infrastructure and no traffic laws or safety regulations, Seamans said the trips were harrowing.

Being in challenging environments is not new to Seamans.

In 2005, after hurricanes Katrina and Rita hit, he traveled with The American Red Cross to document relief efforts along the ravaged Gulf Coast.

And in 2010, in a freelance project for Paradox Sports and Amp’d Outdoors, he photographed two men with below-the-knee right leg amputations as they scaled rock and ice on the sheer 3,500-foot south face of Moose’s Tooth in Alaska.

Seamans said a lot of the food in Sierra Leone was good, including the best ginger snaps he’s ever eaten and seasoned goat meat served on a stick.

He still dropped 25 pounds in 21 days.

Seamans said Americans can help to better the lives of Sierra Leonians.

“As Westerners, we are consumers of diamonds and have a direct link to Sierra Leone. I feel very fortunate to be poor in America and not poor in Sierra Leone,” he said. “I have a sense of guilt, too.”

Seamans described Sierra Leone as a tough place with beautiful, kind and tolerant people.

“The whole place is so heartbreaking.”

Beth Staples — 861-9252

bstaples@centralmaine.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.