On a hot Saturday morning in late June, a handful of cars towing watercraft lined up by the Monmouth boat launch, extending nearly halfway up the packed parking lot.

Emily Lucas walked around the vessel closest to the water, looking carefully at its motor, propeller and anchor.

Lucas, a courtesy boat inspector, was searching for traces of invasive plants trapped in the boat’s components.

She thanked the owner and told him to have a great day, a sign his boat was clean. He could now enter Cobbossee Lake which, at 5,543 acres, is among the largest water bodies in central Maine.

Emily Lucas reaches in and checks a trailer roller for vegetation June 25 before a boat gets put in the water at a boat launch on Cobbossee Lake in Monmouth. Joe Phelan/Kennebec Journal

Then, she jotted down some notes before quickly moving onto the next boat in line.

Although inspectors are on the lookout for invasive plant pieces or aquatic animals, it’s not unusual to come up empty-handed. Just one in every 1,000 boat inspections results in the identification of an invasive plant in Maine.

Despite the low detection rate, lake associations and bass clubs across the state are increasingly dedicating more time and money to performing these inspections during the summer boating season. Not doing so could cost them hundreds of thousands of dollars down the road, with near-permanent consequences to water bodies and surrounding properties.

Since discovering two invasive species — Eurasian watermilfoil and European frog’s bit — at Cobbossee Lake in 2018, local associations have ramped up their efforts to rid the lake of harmful plants and protect other nearby water bodies.

State legislators have also taken greater interest in the issue, passing a law earlier this year requiring a task force to study invasive aquatic plants and recommend policies to better control the problem.

Invasive species of milfoil pose the largest threat, as a single fragment of the plant can break off and spread throughout an entire lake, changing the entire ecosystem. This will not only hinder boaters and swimmers, but harm native plants and animals and reduce surrounding property values.

Emily Lucas reaches in and checks a trailer roller for vegetation June 25 before the boat gets put in the water at a boat launch on Cobbossee Lake in Monmouth. Joe Phelan/Kennebec Journal

Officials say courtesy boat inspections are the first, and most important, step in ensuring that the plants do not continue to spread.

This season, Cobbosseecontee Lake Association has budgeted $54,000 for courtesy boat inspectors from Friends of the Cobbossee Watershed, who are staffing the lake’s two public landings from 7 a.m. to 5 p.m. every day from Memorial Day to Labor Day weekend.

FOUR ‘SAVES’ IN SEVEN YEARS

Pennesseewassee Lake has never been infested by invasive plants, and the Lakes Association of Norway has taken great pains to keep it that way.

From Memorial Day to Labor Day, a paid courtesy boat inspector waits at the public boat launch in Lake Pennesseewassee Park, with two three-hour shifts each weekday and 12-hour coverage for both Saturday and Sunday.

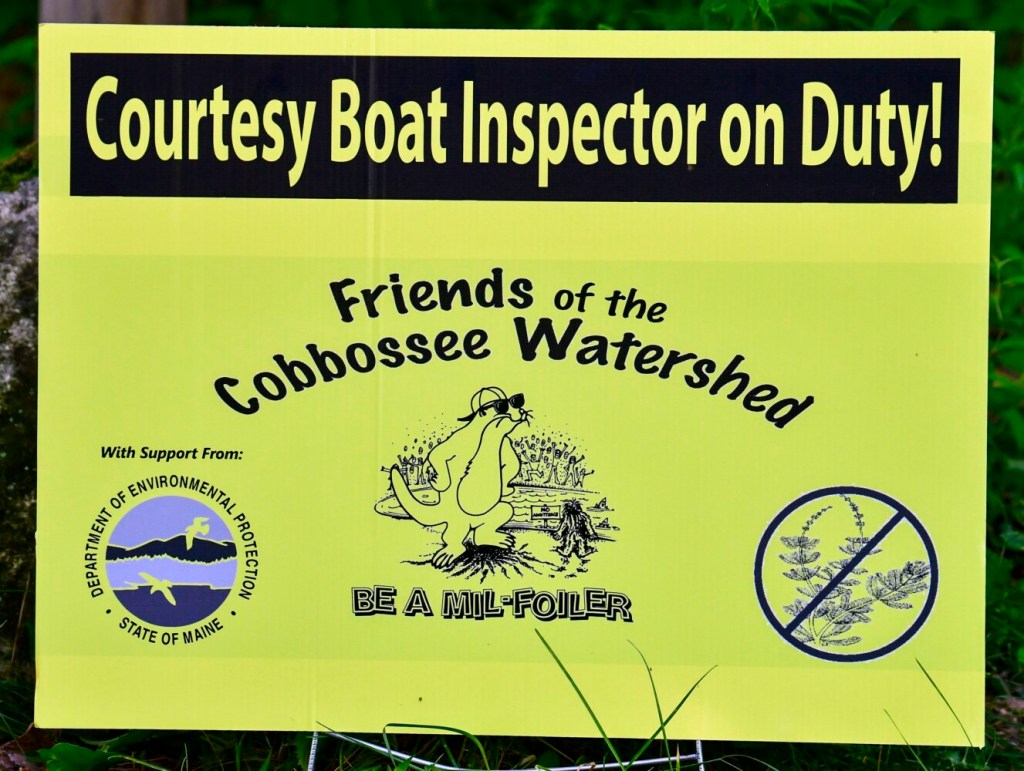

A Friends of the Cobbossee Watershed boat inspection sign is posted at a boat launch on Cobbossee Lake in Monmouth. Andree Kehn/Sun Journal

Since 2018, Norway inspectors have found just three invasive plant fragments and one invasive mollusk hitchhiking on boats entering the lake out of 10,000 inspections. Inspectors often refer to these finds as “saves,” likening themselves to lifeguards for the lake.

Started in 2015, the program ran for three seasons before identifying its first invasive species.

Even so, Sal Girifalco, president of the Lakes Association of Norway, says the program is worth it.

“A quarter-of-an-inch piece (of an invasive plant) is all it takes,” he said. “The primary responsibility for not introducing an invasive species into another waterbody lies with individual boaters. A five-minute inspection before launching would stop most of the spread, but unfortunately not all boaters take that time.”

Instead, lake associations and bass clubs are taking a greater role in slowing the spread of invasive species.

Since 2012, the total statewide inspection hours has risen by an average of 400 hours per year, to a total of 44,858 in the summer of 2021. However, the number of registered inspectors has actually decreased, from 773 in 2012 to 614 in 2021, indicating fewer people are taking on more responsibility to monitor for nonnative plants and animals.

It’s unclear to what extent the statewide increase in inspection hours is the result of new inspection programs versus expanding established programs.

Over the last decade, the number of waterbodies with inspections has fluctuated, with a high of 130 in 2019 and a low of 116 in 2014. In 2021, 122 bodies of water had some kind of inspection program, 17 of which were identified to have at least one invasive species.

FEW SUCCESSFULLY REMOVE

The organizations tasked with protecting Cobbossee Lake know how hard invasive plants are to remove once an infestation starts.

In 2019, the year after Eurasian watermilfoil was first discovered there, the Maine Department of Environmental Protection administered an herbicide treatment. The herbicide used, ProcellaCOR, contains a synthetic plant hormone that kills the plant by making the cells grow larger than they should.

Officials were hopeful it had eradicated the invasive.

But a fragment was found in the northeast corner of the lake in 2020, and another piece appeared around Farr’s Cove, about halfway down the lake, near the end of last year.

A fishing boat trolls by June 25 as boaters come and go from the the boat launch on Cobbossee Lake in Monmouth. Joe Phelan/Kennebec Journal

Two organizations are working together to eliminate invasive plants in Cobbossee Lake: Friends of the Cobbossee Watershed and the Cobbosseecontee Lake Association.

Friends of the Cobbossee Watershed consists of experts and volunteers who work to ensure the entire Cobbossee watershed, a 217-square-mile drainage basin, is clean and free of invasive plants and pollutants.

In addition to hosting camps and programs dedicated to educating the public about the importance of keeping the lakes clean, Friends of the Cobbossee Watershed’s “Mil-Foiler” program is dedicated to ridding the 28 lakes and ponds in the watershed of invasive plants.

John Stanek, vice president of Cobbosseecontee Lake Association, said boat inspections are the only way to prevent lake infestations.

“We have in the lake variable leaf milfoil and know that it came from the upstream Annabessacook Lake, where there was a serious infestation and it remains a problem,” he said. “Eurasian watermilfoil could only have come from a plant fragment carried by a watercraft from another infested waterbody.”

Once an invasive plant takes root, it is extremely difficult to remove, often costing hundreds of thousands of dollars, if not millions, over decades.

Cushman Pond in Lovell is one of the lucky ones. In 2021, the 37-acre pond was declared free of variable milfoil 27 years after it was first identified.

Residents painstakingly dove to the bottom of the pond several times year after year to remove the milfoil, not unlike weeding a garden. One leader of the effort estimated that $200,000 was spent conducting surveys and searching for the plant since it was first discovered.

Invasive plants have been successfully eradicated from just nine of 68 infested water bodies in Maine, including five which had variable milfoil, three with hydrilla and one with Eurasian watermilfoil, according to data from the Maine Department of Environmental Protection.

‘LAST LINE OF DEFENSE’

During the morning shift one Friday earlier this month, inspector William Eshleman of Norway saw just five boats. The weekends, he said, are far busier.

It can be tough to conduct inspections when the owners want to get out on the water as fast as they can, Eshleman said, adding that balancing speed and education is a particularly important skill of the job.

In addition to the boat, he also makes sure to check the trailer it rests on.

Owners could face a fine up to $500 the first time if they neglect to clean all plant material from their boat before launching into Maine waters, with subsequent fines as high as $2,500. However, Eshleman said it’s difficult to enforce.

He isn’t responsible for administering fines, nor does he have the power to do so. That’s the job of Maine’s Warden Service.

Eshleman believes it’s a good thing courtesy boat inspectors are not responsible for penalizing lax owners. Their foremost goal is to confirm boats do not transport invasive species, he said, and a fear of fines could discourage owners from participating in the optional inspection.

William Eshleman of Norway examines both boats and trailers for any signs of invasive plants or wildlife June 26 at the Lake Pennesseewassee boat launch. Andree Kehn/Sun Journal

It also means that Eshleman and the other inspectors across the state have no power to bar someone from launching a boat, even if it has suspected invasive species attached. The program relies on the cooperation of owners.

Courtesy boat inspectors typically submit their inspection data electronically to the state, where it’s stored in a central database.

Chris Cobbett of Paris brought his 26-foot Bayliner Trophy to the launch that Friday for a water test before using it for commercial tuna fishing.

Cobbett said he “absolutely, every time” checks his boat before launching. His primary purpose is to check the lights, propeller and other mechanical components of the boat. Still, invasive plants are on his mind.

“By default, I’m checking that nothing has grabbed on that shouldn’t have,” he said.

Still, a man who launched his boat before Cobbett admitted that he never does his own inspections.

“This is the last line of defense,” Eshleman said, referring to courtesy boat inspectors. “Once it’s in the water and there’s a patch of it, it’s game over.”

William Eshleman greets Rick Dillon of Norway, who is preparing to launch his boat June 26 in Lake Pennesseewassee for the first time this the season. Eshleman is a courtesy boat inspector for the Maine Milfoil Project and checks boats as they are launched and when they come out of the lake. Andree Kehn/Sun Journal

‘EVERYONE’S REALLY NICE ABOUT IT’

One Saturday last month, Lucas, the courtesy boat inspector, worked a six-hour shift at the Monmouth boat launch.

Lucas said she focuses each inspection on problematic areas of the boat, like the motor, the propeller and anchors. She said plants can also get stuck between the boat and the trailer.

“I’m looking for any and all plants and removing them,” she said, “because even if they’re not invasive, they shouldn’t be going from one lake to another, because that’s how the problems will start, so I’m just removing everything I see.”

During a momentary lull in boat inspecting June 25, Emily Lucas calls and checks in with another Friends of Cobbossee Watershed inspector at a boat launch on Cobbossee Lake in Monmouth. Joe Phelan/Kennebec Journal

She said the actual inspection takes between one or two minutes, but that she will also talk to people about the importance of inspections and dangers of invasive plants as long as there isn’t a huge line of boaters waiting.

She said the busiest times are typically in the morning at 9, 10 and 11.

“There are definitely always boats trickling in,” she said, “but no one’s like ‘I’m going to go boating at 10:37.’ They pick times and it’s usually on the hour, and there’s a big rush.”

She said the Monmouth boat launch is the busiest launch in the entire watershed.

Since she began inspecting boats last summer, Lucas said out-of-staters are usually curious about the process, but all of the boaters she’s met have been receptive.

“They’re like, ‘Oh, that’s really cool of you to come check out our boat and make sure it’s safe,’ and will usually ask for more information,” she said. “And the in-staters know the drill. They’ve seen us a lot before. Everyone’s really nice about it. I’ve never had anyone say ‘No, you can’t look at my boat.'”

Friends of the Cobbossee Watershed Director Tamara Whitmore said the organization’s boat inspections account for about 13% of all boat inspections in the state, and that boating activity spiked significantly in 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic first hit, and leveled out last year.

Across 10 public boat launches on eight different lakes in the watershed, Whitmore said they conducted roughly 14,000 inspections in 2020.

Even though the lake still falls under Maine’s rapid response program, which is when the state takes the lead in eliminating invasive plants, Whitmore said they understand that there is a deficit of resources on the state level, as they have “too much to oversee.”

“So that’s where the partnership between the Cobbosseecontee Lake Association and the Friends has really struck out,” she said, “to step up and take care of the lake as best as we can.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.