Manufacturers across the United States are targeting schools and colleges to let young people know there is more to manufacturing than pulling levers on an assembly line.

“People still have the idea that manufacturing is a dirty dungeon place,” said Andy Bushmaker of KI Furniture, a maker of school desks and cafeteria tables in Green Bay, Wis. The goal, Bushmaker said, is to get people to see manufacturing jobs as the high-tech, high-skilled and high-paying careers they can be in the second decade of the 21st century.

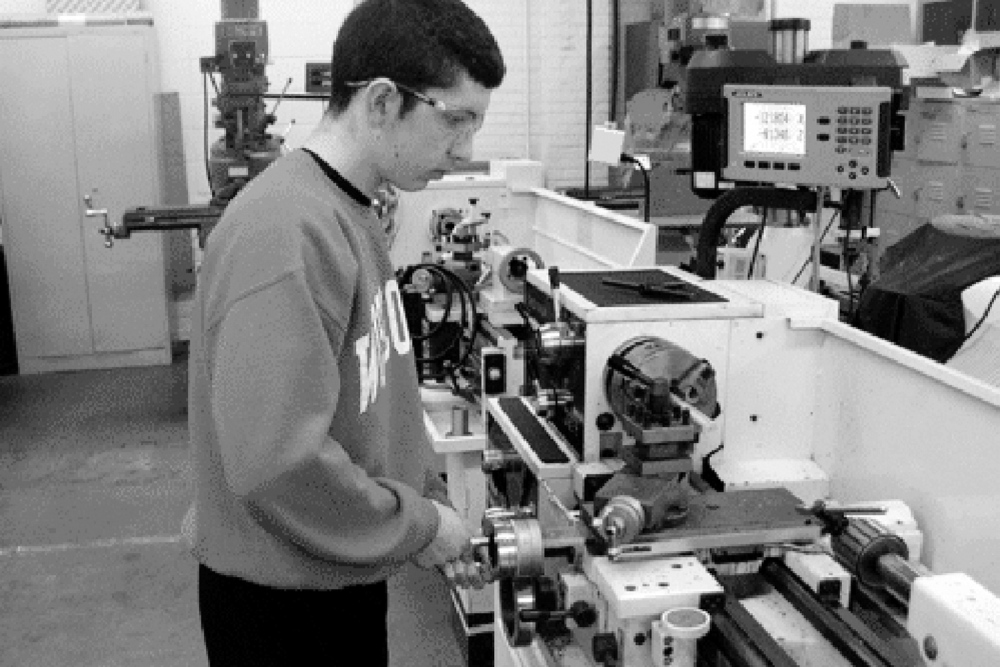

Today’s manufacturers, whether they are making cars, airplanes or iPhone parts, are looking for engineers, designers, machinists and computer programmers. Manufacturing has moved from manual mills and lathes to computerized numerical control equipment and 3-D printers. Hand-held welders are being replaced with robotic welders. Industrial maintenance mechanics no longer need to know how to use a wrench, but have to be able to operate a “programmable logic control,” or a digital computer, to fix the machines.

Many of the jobs pay well — the average manufacturing worker in the United States earned $77,505 in 2012, including pay and benefits — but they can be hard to fill.

Nationwide, U.S. employers reported last year that skilled trades positions were the most difficult to fill, the fourth consecutive year this job has topped the list, according to the 2013 Manpower Group talent shortage survey. A 2011 industry report estimated that as many as 600,000 manufacturing jobs were vacant that year because employers couldn’t find the skilled workers, including machinists, distributors, technicians and industrial engineers, to fill them.

In Wisconsin, manufacturers figure they will have to fill 700,000 vacancies over the next eight years because of retirements. Employers like KI Furniture are using an array of programs to attract people to fill the pipeline, including youth and adult apprenticeships, job training, even YouTube videos. KI’s own video includes an automation specialist who describes his work as, “the CSI of the automation world.”

Wisconsin is one of many states where employers, schools and chambers of commerce are working together—often with the help of state or federal grant money—to prepare students and the unemployed for hard-to-fill manufacturing jobs.

Elsewhere

Teams of high school students in northeast Ohio get to design and build their own working robots with help from manufacturing companies as part of a “RoboBots” competition sponsored by Alliance for Working Together, a coalition of manufacturing companies. It has partnered with Lakeland Community College to develop a degree program working with an area high school to introduce an apprenticeship program starting in ninth grade.

In Massachusetts, Siemens, the global industrial giant, announced this spring that it would donate nearly $660 million in software to a dozen technical schools and colleges in Massachusetts to help train a new generation of workers in advanced manufacturing.

In Pittsburgh, the Three Rivers Workforce Investment Board teamed up with Carnegie Mellon, local community colleges, unions and apprenticeship programs to develop a “virtual hiring hall” for advanced manufacturing under a $3 million federal “innovation” grant.

Industry leaders in Kansas, Georgia, Rhode Island and Delaware have joined the “Dream It. Do It.” campaign started by the Manufacturing Institute, an affiliate of the National Association of Manufacturers. The goal of the program, which now has participants in 29 states, is to recruit students into manufacturing by educating parents, teachers and counselors about employment opportunities.

Roving Computer Lab

KI Furniture finds many of its future workers through involvement with the NEW (North East Wisconsin) Manufacturing Alliance, which consists of manufacturers, schools, chambers of commerce and workforce development boards. The members work together to promote manufacturing careers, particularly to young people.

“It’s critical for us to continue to promote manufacturing careers as more and more retirements happen,” Bushmaker said.

The NEW Manufacturing Alliance has received about $200,000 in state workforce development training grants over the last eight years, including $40,000 from Republican Gov. Scott Walker’s Fast Forward grant program. The alliance has partnered with Northeast Wisconsin Technical College, which received $15 million in federal funds in 2012, when the U.S. Labor Department announced it would provide $500 million to community colleges and universities around the country for innovative training programs.

Manufacturing remains an important part of the Wisconsin economy. More than 16 percent of Wisconsin workers are in manufacturing, more than any other state save Indiana, the National Association of Manufacturers reported in 2013. In northeast Wisconsin, manufacturing makes up 23 percent of all jobs.

Every year the NEW Manufacturing Alliance surveys its members to see which jobs are hard to fill and then teams up with local high schools and the Northeast Wisconsin Technical School to come up with ways to encourage students in those careers, providing classes and a pathway to those jobs.

Welding, for example, used to be one of the most difficult jobs to fill. Only 28 welders graduated from the Northeast Wisconsin Technical School in 2005. But five years later, that number jumped to 109 graduates. Today, 180 welders are enrolled in the program and welding has dropped to No. 8 among the hard-to-fill jobs, said Ann Franz, director of the NEW Manufacturing Alliance.

Skilled machinist jobs are now the hardest to fill in northeast Wisconsin. Enter a roving 44-foot trailer and truck equipped with computer numerical control, manufacturing tools and 12 work stations that travels to rural school districts to provide students with hands-on training. Students who learn in the “Computer Integrated Manufacturing Mobile Lab” can earn college credits.

And this fall, the NEW Manufacturing Alliance is working with the Green Bay Area School District and Northeast Wisconsin Technical College to launch a new lab located at West High School called Bay Link Manufacturing that will give high school students in the Green Bay area “real world projects” from local manufacturing companies, allowing them to use computerized numerical control manufacturing tools.

The alliance also has produced videos that local teachers use to teach practical applications for math on a production line — from trigonometry to software optimization to robotics.

‘Manufacturing Hubs’

President Barack Obama wants to build a network of “manufacturing hubs” to bring together companies, universities and other academic and training institutions to develop the latest manufacturing techniques. The president announced in February a new public-private partnership near Detroit devoted to developing new types of light weight metals and another in Chicago to concentrate on digital manufacturing and design technologies.

Manufacturing hubs already have been established in Youngstown, Ohio, and Raleigh, N.C. The initiatives use money from the U.S. Defense and Energy departments that is already budgeted, since Congress has balked at the president’s $1 billion price tag for the hubs.

As part of this effort, employers such as Dow, Alcoa and Siemens are partnering with community colleges in Northern California and South Texas on apprenticeships in advanced manufacturing occupations, such as welding. In Minnesota, a coalition of 24 community colleges, led by South Central College, is pioneering a statewide apprenticeship model in mechatronics.

This spring, the Obama administration announced $100 million in federal grants for creating or expanding apprenticeship programs. At the state level, Rhode Island has enacted the state’s first registered manufacturing apprenticeship program, and last year Connecticut increased the manufacturing apprenticeship tax credit to $7,500 from $4,800.

Apprenticeships are “underappreciated and underutilized,” according to U.S. Secretary of Labor Thomas E. Perez. Perez said that when he hears a parent say, “I don’t want my kid to do an apprenticeship; I want my kid to go to college,” he points to the program at Tampa Electric in Florida, which pays apprentices about $32 per hour as they learn how to maintain and repair electrical power systems and equipment. They can earn as much as $70,000 as full-time employees. “Some of the upper management at Tampa Electric started out as lines people,” Perez said.

“There is a bright future in America for people who work with their hands,” Perez said. “We need to do a better job of marketing it, explaining to parents and others that these jobs are tickets to the middle class.”

Pamela M. Prah is a staff writer for Stateline.org, a nonpartisan, nonprofit news service of The Pew Charitable Trusts that provides daily reporting and analysis on trends in state policy.

Send questions/comments to the editors.