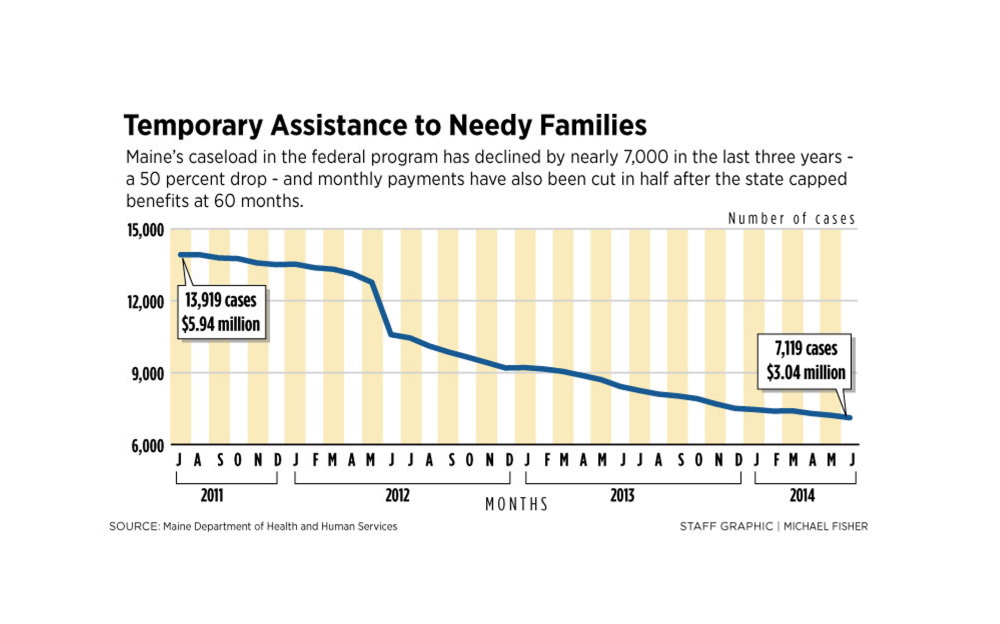

In less than three years, Maine’s caseload under the federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program has been sliced nearly in half, to about 7,600 cases per month, a drop largely attributable to a 60-month cap on benefits instituted in 2012.

The diminished caseload, and the resulting decrease in spending, has freed up tens of millions of dollars under the state’s annual TANF block grant, which has not been reduced even though the number of cases has decreased.

Responding to a Freedom of Access Act request submitted by the Portland Press Herald, Maine Department of Health and Human Services spokesman John Martins said his agency could not immediately provide a breakdown of how the assistance funds have been spent over the past four years.

DHHS Commissioner Mary Mayhew said the money has given the state financial flexibility, allowing it to better fund job training, education, transportation and other programs that she says will do more to reduce dependency on public assistance. The approach reflects Gov. Paul LePage’s position that welfare programs need to be reformed, largely because they encourage dependency rather than self-sufficiency.

“We are in the process of continuing to evaluate other opportunities to make additional investments,” she said in an interview Wednesday. “The previous system failed to assist vulnerable families in a manner that would help to support greater stability and to help them support themselves.”

The cap on TANF benefits was part of Gov. LePage’s biennial budget, submitted in 2011, that won the support of a then-Republican majority in the legislature.

Critics say the 60-month limit has done nothing to address needs across the state and argue that low-income Mainers are being forced to look elsewhere for assistance, which has only shifted the burden to municipalities.

Portland, Lewiston and Bangor, Maine’s three largest cities, account for roughly 75 percent of all general assistance spending. All three have seen spending increase considerably since the cap went into effect.

“When you’re looking at public policy, you have to look for solutions that benefit all parties,” said Kate Dufour, a policy analyst with the Maine Municipal Association. “(The TANF cap) did not do that.”

OTHER PROGRAMS GET $10M

From July 2010 through June 2011, Maine distributed $73.8 million in TANF benefits to an average of 14,151 families a month.

Over the next year, the average monthly caseload dropped slightly, to 13,260, and total spending decreased to $68.1 million.

However, since the 60-month cap was instituted in June 2012, the number of TANF cases has dropped precipitously.

From July 2013 through June of this year, the average monthly caseload was 7,617, and spending declined to $38.3 million.

Yet while the TANF caseload has dropped, Maine’s annual block grant, about $78 million, has remained unchanged.

For the 2013 fiscal year (July 2012-June 2013), Maine transferred about $10 million of its funds to other programs (which is allowed under federal law) and spent only $45.8 million.

That left $24.6 million unspent, which was rolled over into the next year.

Although Mayhew wouldn’t specify how the assistance money was spent, she said it has used in a variety of areas, including improved partnerships with the departments of Education and Labor, and a recent contract with Maine Medical Center’s vocational rehabilitation program to provide comprehensive assessment of TANF clients.

“We’re trying to support more effective pathways to employment, such as education and work training, to break the cycle of generational poverty and dependency on these poverty-based programs,” she said.

DRUG TESTS AND INSPECTORS

Under federal TANF rules, states can spend “in any manner that is reasonably calculated” to achieve the program’s goals. Those are to help needy families so children can be cared for in the home or by the family, to end dependence on government benefits, to reduce out-of-wedlock pregnancies, and to promote the formation and maintenance of two-parent families.

Some of Maine’s TANF block grant funded a $925,000 contract with the Alexander Group, a Rhode Island-based company hired to assess Maine’s social service programs. The group produced a series of reports, at least two of which were found to have plagiarized from other sources.

LePage was forced to cancel the state’s contract with the Alexander Group earlier this year and withhold about $450,000 in payments.

Last week, Martins said the TANF block grant funds also would be used to pay costs associated with a new drug-testing program for convicted drug felons who apply for or receive the program’s benefits.

Mayhew said the money also has been used to hire new inspectors for child care facilities in response to problems that surfaced this year.

Robyn Merrill, a senior policy analyst with Maine Equal Justice Partners, an advocacy group for low-income and homeless Mainers, would like to know exactly how the state has been spending the federal money.

“I don’t think there has been a lot of transparency,” she said, “but we still think the money should be going to these families, because it can often be the difference between being homeless and having a place to live.”

COMMUNITY BURDEN GROWS

Dufour, at the Maine Municipal Association, said she has heard from communities who are seeing their general assistance spending increase as a direct result of the TANF cap.

“Caps don’t address need,” she said. “They have to go somewhere.”

She said the cap may have improved the outlook for that program, but it also shifted burden.

Bangor, Lewiston and Portland all have seen big jumps in their general assistance budgets since 2012.

Rindy Fogler, who oversees the general assistance program for the city of Bangor, said the city has spent an extra $217,382 in the last two years to individuals who reached the TANF limit.

Lewiston officials did not respond to requests for information, but have said previously that the TANF cap has led to increased general assistance spending.

In Portland, the city spent $8.3 million on general assistance for the 2012 fiscal year, which ran from July 2011 through June 2012.

For the 2013 fiscal year, that increased to $9.8 million.

Robert Duranleau, Portland’s social services director, said in the last year an extra $185,000 has been given in general assistance to clients who have been timed out of TANF.

Mayhew, the DHHS commissioner, said the changes have been a big undertaking and have not always been popular, but she believes the result will be fewer people relying, long-term, on programs such as TANF. Others, though, say Gov. LePage is playing politics and is not offering real solutions to overcoming poverty.

“There is no doubt that (the LePage administration) is trying to make it harder for people to get benefits,” said Merrill, the Maine Equal Justice Partners analyst. “But that hasn’t made problems go away.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.