YARMOUTH — George Mason understands what it means for an artist to plug into a community. He’s done just that most of his professional life, from his early work as founding board member of Watershed Center for the Ceramic Arts in Newcastle to the 30-plus public art projects he’s completed in schools and municipal buildings across Maine.

When Mason heard about an artist residency program in Yarmouth that asks artists to embed themselves in the community for a month, he was immediately interested. Most residencies offer artists isolation. The Kismet Foundation’s new residency is different: Mason spends his March evenings in a private Cousins Island cottage with million-dollar views and abundant charm, but his days are spent in town hosting open studios, workshops and demonstrations and giving talks about his art.

Mason is the first artist-in-residence of the Kismet Foundation, which uses art and creativity to connect segments of the community. Yarmouth resident Tamson Bickford Hamrock began the foundation to encourage creativity for the greater good of the community.

Hamrock grew up in Yarmouth, a daughter of town icon Erv Bickford, who was one of Yarmouth’s longest-serving councilors. She spent many years pursuing a career in banking overseas, and returned to Yarmouth in 2010 to help care for her ill father, who died in 2012. She owns the Cousins Island cottage that artists use as living quarters. Her home is next door.

“Yarmouth is about community, and we’re all about the arts. We are looking for artists who embrace community,” she said.

The Kismet Foundation residency is Hamrock’s experiment to see if art can help knit a town together and offer points of connection. As the inaugural resident artist, Mason is something of a lab rat. It’s too early to say if Hamrock’s vision will pan out, but Mason is giving it his best shot. He’s working with art students at Yarmouth High School, he gave a talk at the Yarmouth History Center and hung an exhibition at Merrill Memorial Library.

The studio associated with the residency is in town, part of the complex where Bickford kept his offices. Hamrock converted those offices, and that’s where Mason turns up to do his work. The studio has an open-door policy.

Other artist-residents might work with different organizations. A novelist might engage with student-writers at North Yarmouth Academy. A musician might teach at 317 Main Community Music Center. It’s open-ended, Hamrock said. “We’re making it up as we go,” she said.

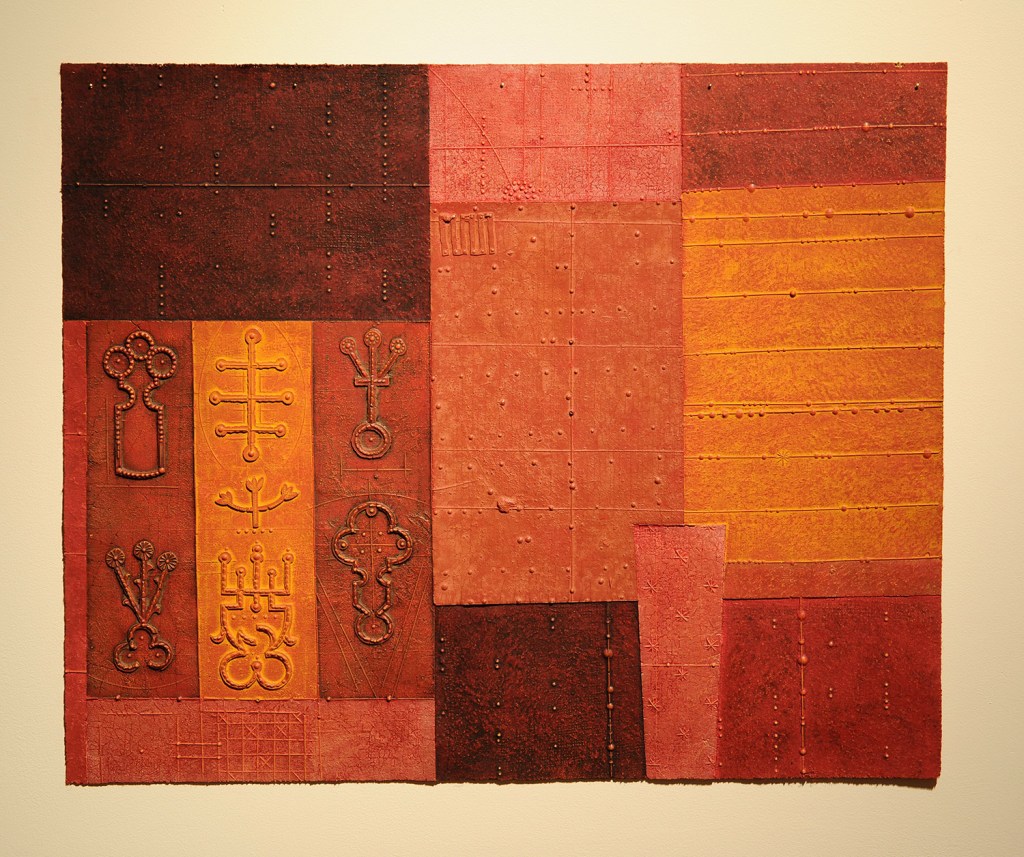

Mason, a ceramicist by training, uses plaster, clay, burlap, pigment, paint and wax to make paintings, prints and sculptural reliefs. Hamrock calls him an alchemist, because he makes beautiful things out of inelegant materials.

Mason lives in Newcastle, and shows his art at the Portland gallery Susan Maasch Fine Art, where he will have a solo show in July. Most major museums in Maine have shown his work, as well.

“I was interested in this because it’s not a cookie-cutter residency,” Mason said. “This residency challenges you to really dig deep into the community, and I like that very much. I’m here for a month, but I’d like to spend more time actually. It feels like we’re just getting going.”

Merrill Memorial Library will host a reception for Mason from 2 to 4 p.m. Sunday. His work is on view in the library through May 2 in an exhibition titled “Embracing Process.” Mason also has loaned Merrill a large wall hanging, “Exchange Pledges,” which is displayed prominently in the newly renovated building. The multimedia panel features glyphs and symbols that suggest Egyptian hieroglyphics.

For Mason, process is everything. The time he spends in the studio creating, experimenting and pushing the utility of his materials is often far more important to him than the outcome of his work. He advances his philosophy during his work in Holly Houston’s advanced art class at Yarmouth High School. He meets with Houston’s students weekly, introducing them to his techniques, materials and attitude.

Art should be fun, Mason tells them. Working in the studio is serious, but it shouldn’t feel that way, he says. It should feel like play.

“I think one of the best things he’s done is taking the students away from the pressure of having to finish a final product,” Houston said. “He wants them to play. Kids are often so focused on the final product, the outcome. Kids just need to experiment with different media.”

Students have worked with wax, plastic and clay. His message: What you make might not be great, but it could lead to something better.

Presuming that notion is true, Houston plans to hang the work that students accomplished with Mason at the local restaurant Clayton’s in May.

Susan Maasch, his Portland gallerist, said Mason’s work fits into the contemporary notion of experimentation, “which brings us right into the now. The nature of contemporary work is to see how it reflects now and this moment – experimenting, rethinking. … I love when artists stay curious.”

Wes LaFountain, a Kismet board member, said he appreciated Mason’s frank discussion about his studio practice, where process is king. It’s a noble notion that rewards artists who are willing to take chances, he said. “George talks about ‘the quality of the encounter’ in the studio, and I really like that idea, because it’s about paying attention to the process and trusting that what you end up with will be interesting.”

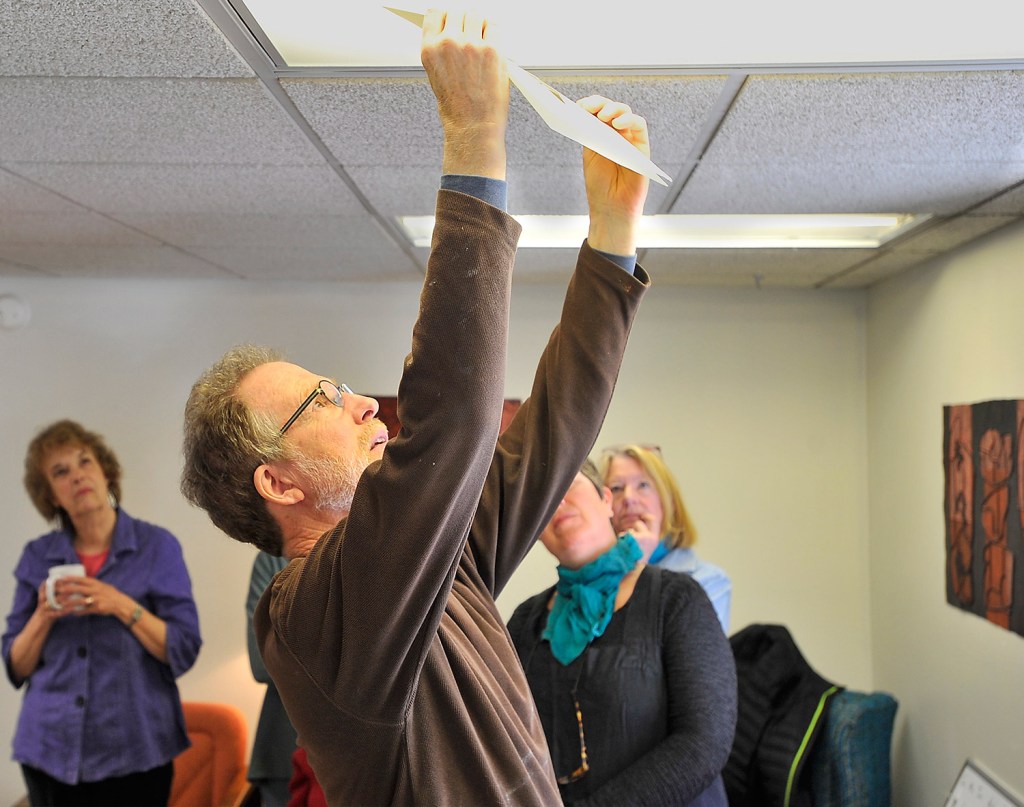

Last week, Mason opened Kismet’s in-town studio to a dozen residents for a demonstration. He cut stencils from linoleum, covered them in colored wax and pressed them onto paper as prints.

“There’s promise there,” Mason said after pulling one print and examining the colors and lines. “Who knows? That’s the start of something. I’m not sure what it’s the start of, but it’s something.”

That sense of wonder and experimentation is at play with the Kismet residency, Hamrock said. She doesn’t know what the outcome will be. But she’s certain it will be good for her town.

Send questions/comments to the editors.