KENNEBUNKPORT — Mary Woodman wasn’t being bold. She just didn’t know any better.

She dipped her toe in the world of photography when a mutual friend suggested she call an acquaintance down Cushing way. Woodman jotted down the name and number, and a few days later called Paul Caponigro and asked if she could talk to him about photography.

She didn’t know that Caponigro was among America’s most accomplished landscape and still-life photographers, a two-time Guggenheim fellow known for capturing the spiritual quality of nature in his black-and-white prints. Had she known, her nerves might have gotten the better of her, and she might not have placed the call. But she didn’t know enough to feel intimidated, and Caponigro proved to be open and welcoming.

That phone call began a long friendship that continues nearly two decades later. During that time, Woodman has built a career that owes much to Caponigro’s influence and friendship – and perhaps to the brownies that she baked for him in appreciation for his monthly critiques. “I think that’s what he was really interested in,” she laughed. “Whenever I had new work to show him, we’d make a date. But he always wanted me to bring food. I think he liked my cooking.”

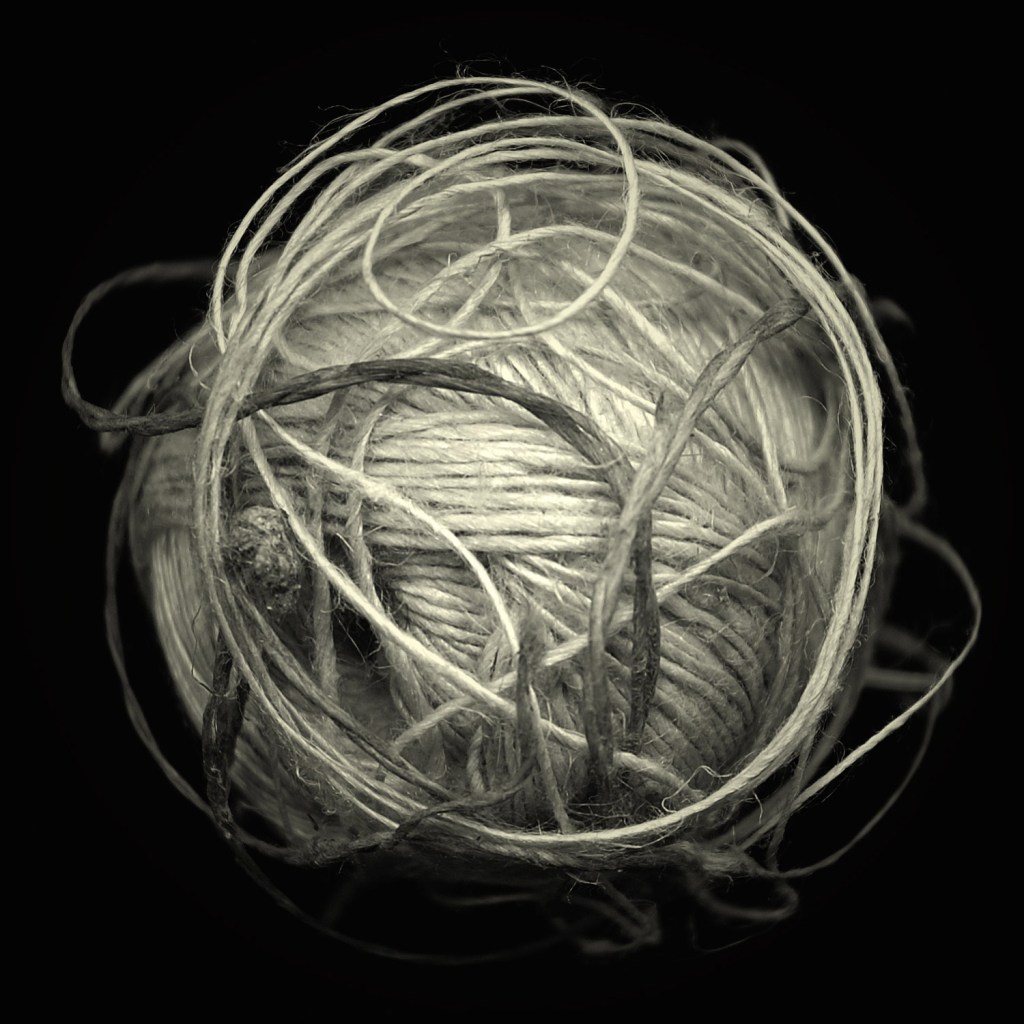

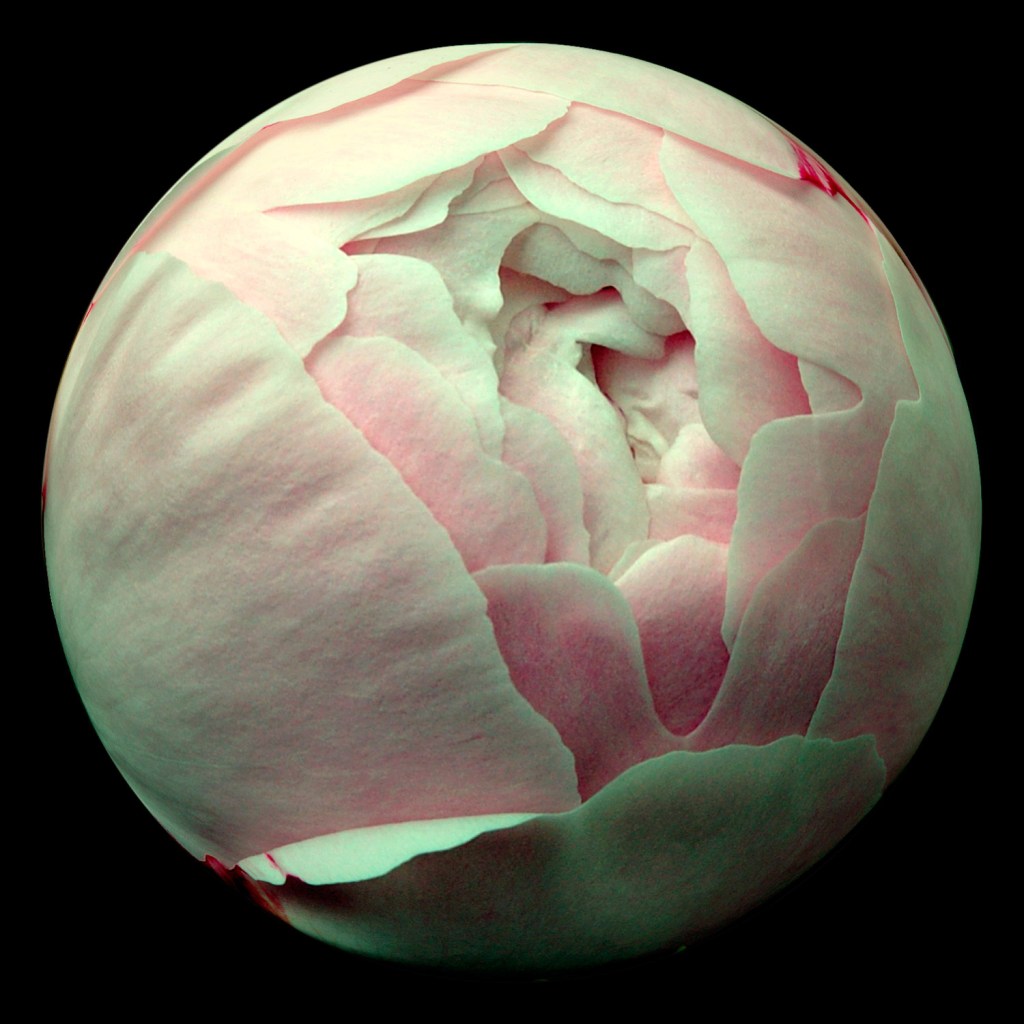

A reluctant and unlikely artist, Woodman has made herself into an accomplished photographer with a national following after spending most of her life raising a family. Working in southern and midcoast Maine and drawing on a love of nature that began as a child growing up in Sanford, Woodman uses Maine’s natural world as a starting point for her photography. She seeks the unexpected beauty in her color and black-and-white photos. She aims to capture a moment in time, suspended in unusual ways: the scuffed laces of a well-used baseball, the frail petals of a breezy coneflower, Maine’s majestic Mount Katahdin shrouded by purple clouds.

These are subjects we know well. Woodman, who embraces digital technology and isn’t shy about manipulating images to enhance their drama, hopes her photographs are different enough to cause us to pause and consider the subjects from a different perspective.

It all comes down to one of the first lessons Caponigro taught her. Anyone can take a picture, he told her. But what is it about a picture that makes it memorable?

There is no single or simple answer, and the answer may vary with each image. Emotion is important, certainly. Composition is critical.

But what it really is, she has come to know, are the intangible traits that every good photographer possesses: instinct, feeling and the willingness to take risks by making an unexpected image of something we see in our everyday lives. Something that makes us pause and take notice, and look again.

Those risks are paying off for Woodman. In February, she won three awards in a national photography contest, and her images have shown up as covers for best-selling novels and textbooks. Most recently, the Irish crime writer Tana French used a Woodman photo of a window as the cover image for her novel, “The Secret Place.”

Her work is part of a group show on view this month at VoxPhotographs on Forest Avenue in Portland.

Heather Frederick, who owns Vox and has represented Woodman since 2009, said the photographer embodies the notion of photographer-as-artist. Woodman makes photo-based art, and uses her digital darkroom as a toolbox the same way a painter employs paints, brushes and knives for applying oils. She’s not afraid to enhance color, blur lines or push the edges of reality. In doing so, her photographs become something else altogether.

“She’s fearless,” Frederick said. “That’s when people come up to an image of hers on the wall and say, ‘I thought you just sold photographs.’ ”

HUMBLE BEGINNINGS

Woodman began humbly, as many hobby photographers do. Her first published photo came in 1999, when she answered an ad from a New England publisher seeking photos for a picture book called “Kittery to the Kennebunks.” She submitted a picture of a lobster boat in the Kennebunk River. It was accepted, and although she did not get paid for the image, the thrill of seeing it in a book motivated her. “That success gave me the impetus to go further,” she said.

Frederick said Woodman defines what being an artist is all about. She has a unique vision, and presents that vision in distinct bodies of work that are different, complete and fully realized. Over the past five years, Frederick says Woodman has presented her with at least five complete and distinct bodies of work, all built around different themes: flowers, sunsets, moonrises and rain, among them.

As she developed her skills and an artist’s eye, her photographs became more complicated and less predictable.

For Woodman, 64, photography represents an interest that she postponed pursuing until she had room in her life to allow it a wide berth. She was busy raising a family, and had other priorities. When she and her husband built a house in Kennebunkport two decades ago, their building plans allowed room for a studio. “I finally decided I had room in my life to do what I wanted, and I also had this great space to use,” she said. “That’s when I went to Rockport.”

Rockport is home to Maine Media Workshops, one of the top destinations for photographers in North America. It also is home to the Center for Maine Contemporary Art, which began promoting photography as contemporary art generations ago. Between the workshops and the art center, Rockport has become synonymous with fine-art photography in Maine.

Woodman took classes at the Workshops, but mostly hung out in galleries and darkrooms. She asked questions and followed leads. That’s how she ended up under Caponigro’s tutelage. For six years or so, she showed up at his home once a month with new work for him to look at – and a box of baked goods. He played the piano for her while they talked. He was a tough critic, she said. He pushed her forward.

But it was her instincts that led her back to nature, where she is most comfortable and where she does most of her work. She was among six kids growing up, and found solace, and quiet, in the woods. For her, the woods were a safe place to indulge her imagination.

Even today, when a storm is forecast, Woodman changes into her foul-weather gear and heads outside. There’s nothing better than a good storm to create atmosphere for a photo, she said.

Woodman never travels without a camera, and isn’t shy about pulling into someone’s yard if she sees something that catches her eye. Her husband knows the routine. When he’s driving and hears her gasp or utter excited words, he knows it’s time to slow the car and look for a place to turn around.

Above all, Woodman has learned to see the things that others overlook.

Send questions/comments to the editors.