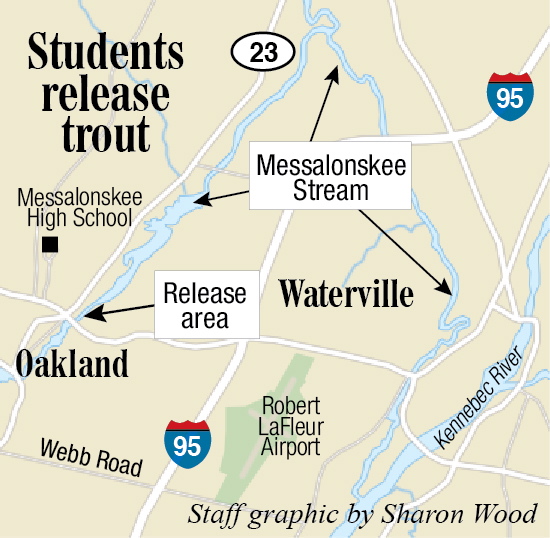

OAKLAND — On a hot, sticky Wednesday morning, a line of excited middle school students stretched up the hill from the wooded east bank of a wide, still part of Messalonskee Stream.

In small groups, the students descended the hill and accepted small plastic cups containing baby brook trout they have raised for the last five months. After saying their goodbyes, the students released the baby trout, or fry, into the stream with the hope that the fish will grow to adulthood and, just maybe, wind up on the end of a local fishing line.

This is the third year that the seventh- and eighth-grade students in Amanda Ripa’s science class at Messalonskee Middle School have released trout into Messalonskee Stream.

Through the experiment, which lasts nearly half the school year, students learn about the fish life cycle through the lens of the ecosystem in their very own town.

“Brook trout are a native species, and they’re also a top sport fishing species, so they are important to our local economy and our environment,” Ripa said.

In January or February, Ripa gets around 300 trout eggs grown by the Maine state fish hatchery.

Throughout the winter and spring, students grow the eggs into tiny fry, barely an inch long, that eventually are used to stock Messalonskee Stream.

It’s a way to connect students with the local natural environment and teach them how parts of the ecosystem are interrelated. The release event is also a way to get students outside and interacting with the native environment, which is an important factor for Ripa, who helped set up an outdoor classroom at the middle school.

Through the experiment, students learn about the trout life cycle, from eggs to fully grown fish, but also about other factors that affect the species, such as pollution — including storm water runoff — and water chemistry. Other schools in the state run similar programs using brook trout or Atlantic salmon.

“We do all the tests to figure out what conditions the trout need to survive,” Ripa said. “They are a cold-water species, and they need lots of dissolved oxygen. They need really clean water.”

Students study the fish, making observations and notes as they move through their different stages. By the end of May, it’s time to release them in a cumulative celebration.

A Styrofoam cooler at Ripa’s feet teemed with the tiny fish Wednesday.

The class had lost 50 to 75 fish since the beginning of the project, Ripa said — much better than last year, when many of the fish died after they hatched partially because of problems with the tank in the classroom.

Ripa and the students hope most of the fry that remain will survive to grow into adult trout, but the recent warm weather has increased the temperature of Messalonskee Stream, which might put their survival in doubt, Ripa said.

“The water temperature of the tank was about 50, and right now the water temperature out there is probably 70 because it has been so warm,” Ripa said, gesturing towards the water.

“If they can swim down quickly and get close to the bottom and hide, then I think most of them will survive.”

While the release was the highlight of the morning, the program takes a comprehensive look at the local ecosystem.

Students rushed between stations, led by volunteers from local groups and government agencies such as Trout Unlimited, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Maine Forestry Service, Colby College and the Belgrade Regional Conservation Alliance. The participation of local experts helps round out students’ education, and Ripa said she has tried to add new volunteers and activities every year.

“Instead of me talking to them about it, they can see other professionals and ask different questions,” she said.

At one site, students learned to identify invasive plants. At another, a group of fly fishermen gave a crash course in casting a fly.

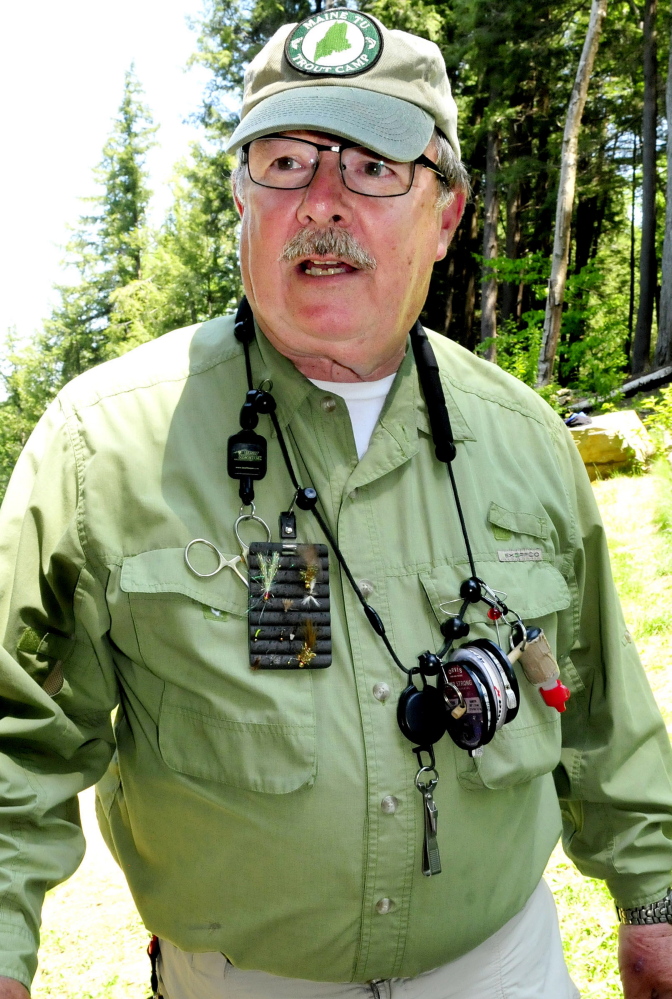

Willie Grenier, from the Kennebec Valley chapter of Trout Unlimited, said his group attends a lot of school events as a way to educate students about the importance of keeping Maine’s rivers clean and healthy, so native species such as brook trout and Atlantic salmon can survive. It was only decades ago that many of the state’s rivers were so polluted that fishing was impossible, and reminding students of the river ecosystem’s fragility is critical to making sure it doesn’t get that bad again, Grenier said.

“People take things for granted until they lose it,” Grenier said.

Nearby, a teacher from Colby’s environmental studies program explains “macroinvertebrates and water quality,” or how insects provide food for trout and contribute to a healthy ecosystem, Ripa said.

At the shore of the stream, near where students were about to release their trout, a team from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service used an electrofishing device, contained in a backpack that looks like a prop from the movie “Ghostbusters,” to show students what other species their young trout might interact with. The device delivers an electric current into the water, enough to stun fish for a few minutes, while the scientists help students identify them.

Despite the heat and humidity, students were upbeat and excited to let the fry they’d raised go free.

“We’re releasing native species. It’s helping the ecosystem,” said Delaney Johnston, an eighth-grader from Oakland. Johnston was waiting in line with her friend Magan Williams. Both girls were in Ripa’s class last year and did the same release event. This year there were more activities and more successful electrofishing. Where the class didn’t catch anything last year, this year the scientists’ nets came up with sunfish, shiners, sucker fish and other species.

Both students said they liked to study science, but while Williams was a fan of identifying and categorizing organisms, Johnston admitted she preferred astronomy, although she’d take the opportunity to get out of a stuffy classroom for a few hours.

“Here at least we’re by the water,” Johnston said.

Peter McGuire — 861-9239

pmcguire@centralmaine.com

Twitter: @PeteL_McGuire

Send questions/comments to the editors.