Modern medicine has been justifiably credited with enabling Americans to live longer, healthier lives. But these same advances have also raised questions about the limits of our health care system to address the challenges a patient faces in his or her final months of life.

A proposal now before the Legislature would allow terminally ill Maine adults to obtain and self-administer a prescription for life-ending medications. While there are reasonable concerns about the potential for abuse and the need to improve end-of-life care, L.D. 1270, for the most part, does a good job of addressing these issues.

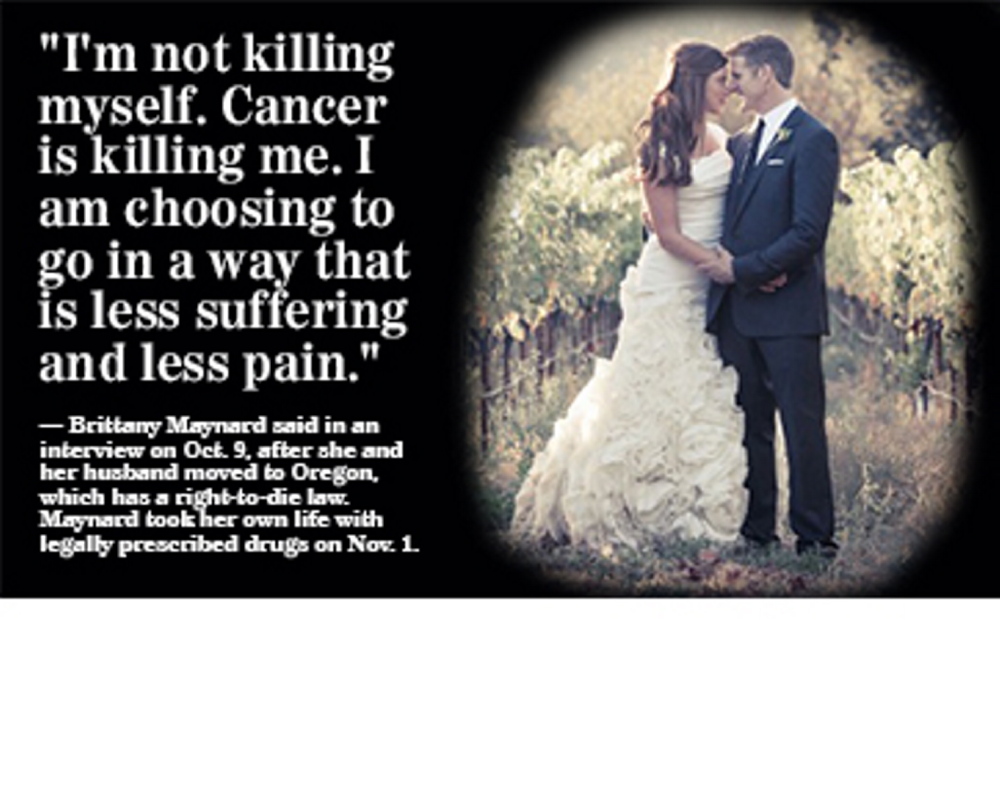

People who are dying deserve to be able to choose to end their lives before they become consumed by suffering, and this proposal — with a few key changes — would provide it.

Titled “An Act Regarding Patient-directed Care at the End of Life,” the bill, sponsored by Augusta Republican Sen. Roger Katz, establishes a multi-step process that starts with two oral requests for the prescription, 15 days apart, from the patient to the physician. The patient must also ask in writing; this third request must be signed by two people who aren’t relatives of the patient or beneficiaries of the patient’s will.

Two doctors are required to affirm that the patient has no more than six months to live, and the patient must be told that they have the right to reconsider at any time. Once all mandates are met, there’s a 48-hour waiting period before the doctor is allowed to write the prescription.

Despite all of these safeguards, opponents of L.D. 1270 have said that patients may feel coerced into taking their own lives out of fear of being a financial burden to their families. Critics’ concerns are valid, given the toll that health care costs continue to take on the average family’s wallet.

Oregon requires state health officials to monitor and report compliance with its assisted-suicide law, a mandate that’s been credited with preventing such abuses. There’s no such mechanism for accountability in L.D. 1270, and the proposal shouldn’t move forward until one is in place.

That said, there’s no reasom that an assisted-suicide law can’t co-exist with efforts to raise awareness of and access to other end-of-life choices: namely, hospice and palliative care. Such outreach has increased the use of hospice among Maine Medicare recipients — which is good news, considering that both supporters and opponents of assisted suicide agree that quality end-of-life care can lessen a terminal patient’s desire to take a lethal medication.

“In any state in which (assisted suicide) would be offered to patients, there would really be a moral imperative to make sure they’re not choosing it because they didn’t receive the best palliative care available,” Dr. Joe Rotella, chief medical officer with the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, recently told Modern Healthcare. (Rotella’s group has a neutral position on physician-assisted suicide.)

Rotella is right: If assisted suicide is a terminally ill patient’s first resort, that’s a sign that our health care system isn’t providing the services that it should. But at the same time, the seriously ill deserve to maintain their autonomy. With provision for official oversight, L.D. 1270 can help those who are suffering make this final choice to end their lives in peace.

Send questions/comments to the editors.