By the time a Navy search team reaches the area where the El Faro sank off the coast of the Bahamas a week ago, it will have only two weeks to locate the data recorder before its battery runs out. During that narrow window, at a cost of $15,000 per day, searchers will try to find the device in hopes it will reveal how and why the 790-foot container ship sank.

Even if the wreckage is located, there is no guarantee that the 55-pound, suitcase-size data recorder is in a position to be retrieved by a remotely operated underwater robot, which must be able to access the bridge area of the El Faro, where the data recorder was attached.

It will take the Navy salvage crew at least seven days to prepare equipment and sail from Norfolk, Virginia, to the area off Crooked Island in the Bahamas where the El Faro is believed to have gone down sometime after Oct. 1, taking with it all 33 crew members, including four Mainers.

Specialists from the Navy, Coast Guard, the National Transportation Safety Board, and the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration are still determining where the search team will start its work, a crucial step, said Mike Herb, the Navy’s salvage director.

“The key to a search is how good is the starting point,” Herb said. “We kind of take every piece of info we can get and melt it down to a starting point.”

Herb estimated that the process could take two months and cost close to $1 million or more, paid for by the NTSB. Different technology would be used to search for the El Faro if the data recorder isn’t located before its battery runs out.

The tools used to find the wreckage will be nearly identical to those used in the unsuccessful search for the wreckage of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370, which disappeared while en route from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing in March 2014.

DATA RECORDER HOLDS CLUES TO SINKING

It is unusual for the Navy to search for sunken ships because it is rare for U.S.-registered ships to sink and result in such a heavy loss of life. Of the 33 aboard, five were graduates of Maine Maritime Academy.

The El Faro set sail from Jacksonville Sept. 29 bound for San Juan, Puerto Rico, carrying containers topside and trailers and vehicles below deck. At the time of its departure, Tropical Storm Joaquin had not been upgraded to hurricane status. The El Faro proceeded on its course until Oct. 1, when it lost propulsion, stranding the vessel in the path of what became Hurricane Joaquin, a category 4 storm that brought 50-foot seas and 130 mph winds when it reached the El Faro. Officials believe the ship sank northeast of Crooked Island in the Bahamas in roughly 15,000 feet of water.

The focus of the search will be locating and retrieving the voyage data recorder, which stores information about the ship’s speed, position, heading and communications. Once the data recorder hits the water, it stores 12 hours of audio recorded from the ship’s bridge, in addition to the navigation information, and begins emitting an emergency “ping” that lasts for roughly 30 days.

The emergency pings could have started as early as Oct. 1.

In an interview Thursday, Herb said the process of dispatching a search team will take at least seven days – roughly four days to transport equipment to the ship that will eventually carry the team to the search site, and another three days to get there.

That means once the searchers arrive in the Bahamas they will have about two weeks before the emergency beacon’s battery goes dead.

SEARCH TECHNIQUES AND CHALLENGES

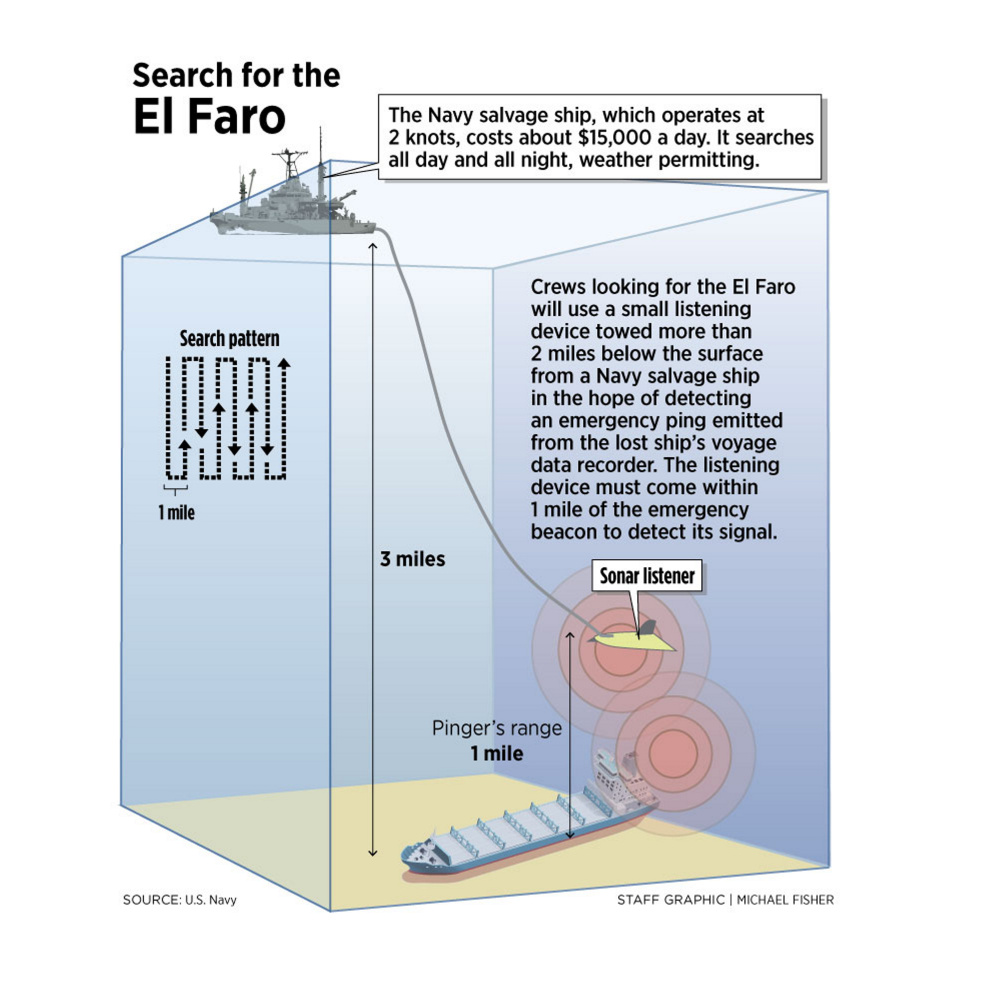

To hear the ping, Navy contractors will drag a listening device at least 2 miles beneath the surface in a slow, methodical pattern.

The emergency pings are usually emitted at 37.5 kilohertz, out of the range of human hearing but readily detectable from a mile away underwater.

The search crew must steer its vessel in a back-and-forth pattern, as if mowing a lawn, with each search lane no more than a mile from the one before it.

Although the U.S. Coast Guard initially searched a surface area about as large as California looking for survivors, the underwater search will be orders of magnitude smaller.

At one point in the Coast Guard’s efforts, the focus narrowed to an area of roughly 300 square miles.

The ship that tows the listening device plods along at about 2 knots, keeping that pace around the clock as long as weather and conditions permit, Herb said.

Even if the wreckage is located, there is no guarantee the data recorder can be retrieved. Although the data collection system aboard the El Faro contained several pieces of equipment, search teams are focused only on the data recorder, a cylindrical, orange device that weighs about 55 pounds and is roughly the size of a large suitcase.

It was attached to the bridge of the El Faro, meaning that if the ship came to rest on the ocean floor upside down, recovering the data recorder would be significantly more difficult, Herb said.

If the data recorder is in a reachable location, the Navy will send down a remotely operated robot the size of a small desk that is equipped with lights, cameras and articulated arms that can cut, grab and manipulate objects underwater.

Send questions/comments to the editors.