AUGUSTA — Henry “Skip” Gates’ late son was brilliant, tallying one of the highest IQ scores ever when tested within the Skowhegan school system, but he didn’t know that snorting or smoking heroin could kill him, just like injecting it could, because no one had ever taught him that.

Gates, of Skowhegan, lost his son, Will Gates, a championship skier studying molecular genetics at the University of Vermont, at the age of 21 to a heroin overdose in 2009.

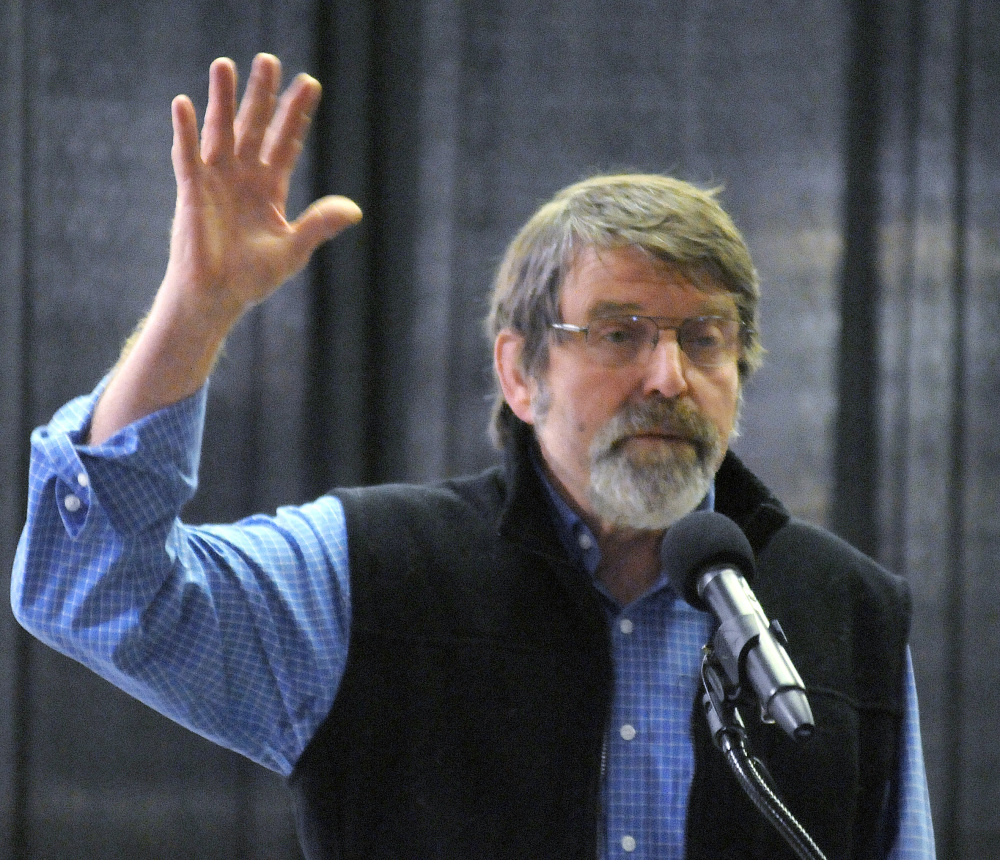

“Brilliance couldn’t protect him from heroin,” Gates said to a rapt crowd of nearly 300 people at a community forum on opiates Monday. “We need to tell kids how dangerous these opiates are. Keep track of your kids. Trust but verify. We can keep our kids alive if we stay in tune.”

Gates said 80 percent of addicts indicate they first became addicted to opiates with legitimate prescriptions. He said 27 percent of people with legitimate prescriptions for opiates, such as painkillers, report feeling some level of dependence. He said kids need to know that painkillers are sometimes needed for treatment, but that they need to be wary about becoming addicted to them.

“Tell your kids, if they feel dependence (on an opiate), run, don’t walk, to their doctor and get help,” Gates said. “If you turn to the streets and continue your dependence, it may be too late.”

Gates retired from his teaching job at Lawrence High School in 2011, he has said, to devote his life to volunteering to educate middle and high school students about the dangers of opiates. His family’s story is featured prominently in the documentary “The Opiate Effect,” which features interviews with Skip Gates and Will’s younger brother, Sam.

Gates also gave similar, in-depth presentations to Cony students during the school day Monday before the evening community forum, “Take Back Our Community, Opiates in Augusta,” was held to seek ways to address what officials say is a growing opiate abuse epidemic.

Dr. Fred White, a psychologist in Augusta, said there is no one solution to the problem.

“It seems we can’t arrest our way out of this problem,” he said. “And we can’t rescue our way out of it. It seems we can’t legislate our way out of it. Or educate our way out if it. But maybe with all these things together, especially with this wonderful community, we have a chance to take Augusta back. What do you think?”

The more than 275 people who packed into the food court at Cony High School responded with applause.

State officials have said overdose deaths from heroin or fentanyl were on pace in 2015 to greatly surpass 2014’s record 100 deaths from those two substances.

In Augusta alone, the Augusta Fire Department responded to 50 heroin overdoses in 2015, up from 26 in 2014 and just six in 2007, according to Fire Chief Roger Audette. He said it is not uncommon to have multiple heroin overdoses at the same time, sometimes in the same apartment, building or neighborhood, as bad batches of the drug come into the area.

Lt. Jason Mills said the department used Narcan, a drug which can revive heroin users who have overdosed, 44 times in 2015 to revive people who weren’t breathing. He said the department’s response time, at five minutes, is a long time for anyone to not be breathing, so even those revived can suffer lasting damage.

Mills said people are wrong if they think they know what an opiate user looks like, if they think they know it’s only junkies.

“I can tell you, as responders, we see that nobody is immune to it,” Mills said. “This is your neighbor next door who hurt his back, who has to have a prescription to go to work to feed his family. This is an athlete coming back from an injury who wants to get back out on the field.”

Mayor David Rollins said he hopes the forum can help inform the community and that participants and leaders can come up with some “actionable responses and next steps” to address the problem. He urged people to take what action they can to help address the opiate epidemic. He encouraged attendees to contact their legislators and urge them to provide funding for treatment programs, not just for enforcement.

State Sen. Roger Katz, R-Augusta, said the state Legislature will consider proposals to add funding to create a 10-bed drug detox facility in Maine where, he said, there are only 16 such beds statewide now and provide more money for peer recovery centers and for treatment for uninsured people.

Katz, who said the turnout Monday was higher than he’d ever seen for any non-sporting event in Augusta, said having a drug problem is not a sign of moral weakness, and addicts should receive help even if they relapse, as a diabetic would continue to receive help even if they didn’t always take their medication.

Darren Ripley, coordinator for the Maine Alliance for Addiction and Recovery, said in the 1980s he was homeless, living in a 1972 Volkswagen van, and he would take any drug and drink anything.

He said he hasn’t had a drink or an illicit drug in 23 years.

“We do recover,” Ripley said. “We are worth it. I made it to here. We don’t need a handout. We need a hand up. That’s what you can do for us.”

Ripley said an alliance program in which peer supporters call people in the early stages of recovery has a 73 percent success rate at keeping people in recovery.

Participants in a question-and-answer session at the forum included Augusta police Chief Robert Gregoire, Kennebec County interim Sheriff Ryan Reardon, Kennebec and Somerset counties District Attorney Maeghan Maloney, MaineGeneral Medical Center Harm Reduction Grants Program Manager Laura St. John, Healthy Communities of the Capital Area Executive Director Joanne Joy and Augusta Schools Superintendent James Anastasio.

Gregoire urged community members to report illegal drug activity to police when they see it. Augusta Police have an anonymous tip line people can call to report such incidents at 620-8009.

Organizations involved in planning the forum also included the Rotary Club of Augusta, Augusta schools, Kennebec Valley YMCA, Augusta police and fire departments, Spurwink and Kennebec Behavioral Health.

Participants broke into small groups for about 20 minutes to discuss possible actions to help address the problem.

Actions cited following those discussions included advocating to the state Legislature for resources to fight the problem, providing more counseling in schools, hiring people who are in recovery, studying using medical marijuana to help some transition off opiates, teaching kids about opiates, visiting and getting involved in the Big Brothers and Big Sisters program, meeting with area clergy to see how they can help and fostering more intensive interaction between drug counselors and small groups of students.

Keith Edwards — 621-5647

Twitter: @kedwardskj

Send questions/comments to the editors.