AUGUSTA — Fear of hepatitis C and HIV brought Eric, a 40-year-old Augusta man, to Next Step Needle Exchange in Augusta.

Situated on Green Street and first open in 2004, the city exchange is a free, anonymous service operated by MaineGeneral Medical Center.

On a recent afternoon, Eric, who declined to provide his last name, said he had taken a break from yard work to ride his bike to the exchange. While there, he returned 200 used needles and received 200 fresh ones. He would be using 50 of those syringes over the next two months, he said, while the rest were for a friend.

“He won’t come here,” Eric said of his friend. “He’s super afraid (of the exchange). He didn’t want his name out there, didn’t want to be seen. I said, ‘Brother, just relax. I’ll take care of it. I’d rather you be safe than sorry.'”

These days, Eric isn’t the only one who is worrying.

The threat of needle-borne infections rapidly spreading in Maine was highlighted by an epidemiologist at the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in an assessment he produced earlier this year.

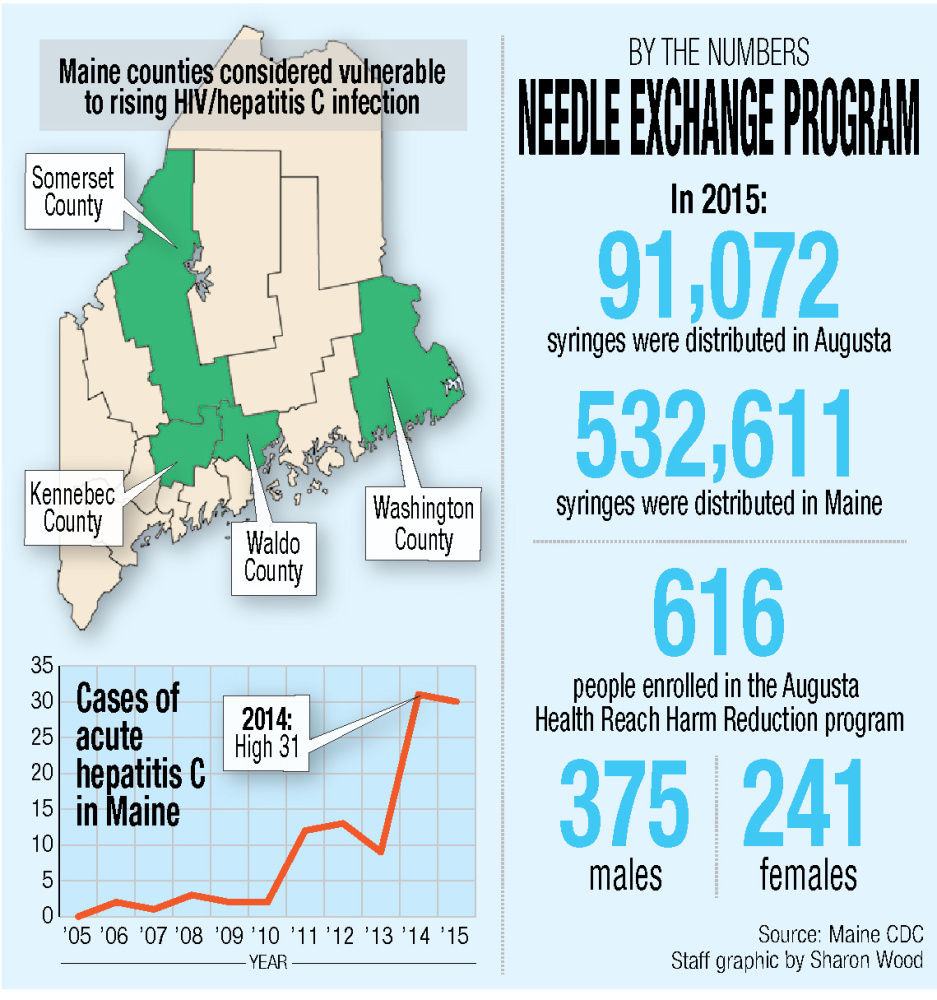

Weighing a range of factors — including overdose rates, unemployment levels and proximity to care facilities — epidemiologist John Brooks ranked how vulnerable injection drug users in each U.S. county could be to an infections outbreak. According to his methodology, intravenous users in four Maine counties — Waldo, Somerset, Washington and Kennebec — may be among the most at risk.

All four counties ended up in the top 200 of his nationwide ranking.

The threat of an outbreak was made plain in March 2015, when Indiana Governor Mike Pence declared a public health emergency after 79 cases of HIV were confirmed in small, rural Scott County in a corner of the state not far from Appalachia. Officials attributed each of the new cases to intravenous drug users who had been sharing needles, and the number of confirmed HIV cases eventually swelled to 191, according to Indiana’s health department.

HIV is the virus that causes AIDS, and to prevent its spread, the state has reversed a longstanding ban on needle exchanges, the facilities where injection drug users can trade their used needles for clean ones and access other prevention services.

The threat of such a Scott County-style outbreak occurring among drug users in Maine has caused harm reduction providers here to rally support for their own efforts: running the state’s six needle exchange sites, trying to open new ones, expanding testing for HIV and hepatitis C and serving as friendly faces for those whose lives have been upended by addiction.

Brooks, describing his assessment as “an exercise,” cautions that local health agencies may have more reliable data. As state health officials point out, his assessment was not designed as a predictor of an outbreak. It also did not take into account programs now in place to prevent infections among drug users, they say, programs that Indiana didn’t have before the outbreak.

Nevertheless, his rankings are a reminder of a public health threat that has quietly accompanied the ongoing epidemic of heroin and prescription drug abuse, which many attribute to the over-prescription of painkillers in the last two decades.

Now, public support appears to be growing for services that prevent the spread of needle-borne infections such as HIV and hepatitis C, which can be personally devastating and costly for the taxpayers who must foot the bill for their treatment.

In 1997, a survey of 1,000 Americans showed 71 percent supported lifting a federal ban on the use of federal funds for needle exchange programs. Last January, Congress finally ended that ban. Three months later, Maine lawmakers overrode a veto of L.D. 1552, a bill that opens up state funding to new and existing exchange programs.

While HIV rates have remained stable in Maine, the state has seen a spike in hepatitis C cases in the last two years, and injection drug use has played a role.

Maine CDC officials found needles were a major contributor to acute hepatitis C infections in 2015, with 67 percent of newly diagnosed individuals reporting they had injected drugs in the previous six months.

Chronic cases of hepatitis C have also been on the rise in Maine with 1,424 reported in 2014, up from 1,259 a year earlier.

In an emailed statement, John Martins, a Maine CDC spokesman, said injection drug use was a cause of the spike in hepatitis C cases. He also said better reporting practices established in 2014 could have led to more reports of the disease.

CONTAMINATED NEEDLES

Eric, the 40-year-old Augusta man, acknowledged the stigma around needle exchange sites but said he is not worried about using the city facility. A former construction worker with broad shoulders, a bushy beard and an affable personality, Eric said he has endured serious back pain for many years and used to abuse Percocet and OxyContin, opioid painkillers that were prescribed to him following back surgery. Before getting on those, Eric said he also used heroin.

Now, after a stint in treatment at St. Mary’s Health System in Lewiston, Eric said he injects about 2 milligrams of Suboxone a day, enough to manage the pain but not enough to incapacitate him. Suboxone is a brand name version of buprenorphine, an opioid medication that some physicians prescribe to addicts trying to get off heroin. But because Eric is unemployed, on disability assistance and unable to get insurance through MaineCare — the state’s version of Medicaid — he can’t get a prescription and must purchase Suboxone on the street, he said.

He injects it because the effects last longer when he does and because the oral form of the drug causes him to be sick.

While he has been fortunate to not test positive for HIV or hepatitis C and works hard to use clean supplies, Eric said he knows a number of drug users who have been diagnosed with hepatitis C. He still worries about catching it himself. On his recent visit, he asked a staff member, Brianna Nalley, if he could get tested the following week.

“I look fit enough, but I’m really sketched out about that stuff. Just to be able to test in a safe, clean environment, it’s great,” he said. “Places like this are a lifesaver. There’s people dying from infections.”

In 2015, the Augusta exchange handed out 91,072 clean syringes to 616 enrolled members, according to state data on certified needle exchange programs. Five other Maine cities have exchange sites: Portland, Lewiston, Bangor, Ellsworth and Machias.

Besides letting adults exchange used needles on a one-for-one basis, the Augusta staff provide testing for HIV and hepatitis C, education on safe practices and advocacy for clients who want to enter treatment, connect with a physician or seek counseling, according to Malindi Thompson, a coordinator for the program.

The exchange also provides alcohol swabs, cotton balls, antibiotic ointment, tourniquets and other items that are used in the injection process and could carry bodily fluids.

The number of reported cases of HIV has remained stable in Maine at about 50 cases a year over the last five years. In 2014, just 3.4 percent of 59 reported cases were linked to injection drug use. The majority, 42.4 percent, were linked to heterosexual sexual contact, and 33.9 percent to male-to-male sexual contact.

But the number of hepatitis C cases has been growing, according to Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention data. Acute cases of hepatitis C — “acute” meaning the disease was contracted in the last six months — more than tripled in 2014 from nine cases in 2013 to 31 in 2014. No cases of disease were reported nine years earlier, in 2005.

Last year, 30 cases of acute hepatitis C were reported, making the infection rate 2.3 cases per 100,000 people. That’s higher than the U.S. rate of 0.6 cases per 100,000 people. Washington and Androscoggin counties had the highest rates in Maine, but cases were also reported in 10 other counties, including Kennebec, Knox and Lincoln.

LIMITED ACCESS

For injection drug users in less populace parts of the state, it’s not as easy as hopping on a bike and heading to the nearest needle exchange. They simply don’t exist outside of Maine’s urban hubs.

That’s one of the reasons Kenney Miller advocated for L.D. 1552. As executive director of the Down East Aids Network and Health Equity Alliance, Miller oversees exchanges in Bangor, Ellsworth and Machias. His organization also operates free HIV testing sites in Augusta and Waterville.

L.D. 1552 directs Maine CDC to allocate funds for new and existing needle exchange programs around the state. The existing ones run on a shoestring, according to Miller, and areas such as Somerset and Waldo counties have no such facilities.

No needle exchanges existed in Scott County, Indiana, before the 2015 outbreak of HIV, and Miller said it wouldn’t take much for a similar outbreak to occur in some of the more sparsely populated counties in Maine. It can take five years for HIV symptoms to show themselves, and given how tight-knit communities of drug users are, Miller said, that’s five years in which a user showing no symptoms of HIV or hepatitis C could avoid testing and unwittingly pass the disease along to his or her peers.

“The risk is greatest down in those rim counties that don’t have those kinds of resources, that don’t have community-based testing programs,” he said. “It’s easy for HIV to spread without anyone being the wiser until it reaches epidemic proportions.”

Some states have been slow to allow needle exchanges or authorize public funding for them because of a long-standing belief that they increase the risk of drug abuse. Such was the case in Indiana before the outbreak in Scott County.

At his home in Kennebunkport in 1992, former President George H.W. Bush captured the sentiment in a written statement: “Distributing free needles to drug users only encourages more drug use.”

But supporters point to research showing that needle exchanges don’t encourage drug use and, if anything, stop HIV/AIDS from spreading at a fraction of the cost.

“For every $1 invested in a syringe, $7 is saved in HIV treatment alone — and this does not include the cost to treat hepatitis C or other maladies,” wrote Rep. Karen Vachon, R-Scarborough, in testimony for L.D. 1552, a bill she sponsored.

A freshman legislator who also works as a health insurance agent, Vachon went on: “A lifetime treatment for HIV costs roughly $367,134 per person. A 12-week treatment program for hepatitis C medication costs roughly $84,000 for those who are diagnosed early; left undiagnosed, hepatitis C destroys the liver. A liver transplant costs $577,100.”

As originally proposed, L.D. 1552 raised $75,000, a third of which would flow to new needle exchange programs. The remainder was supposed to support the state’s six existing exchanges.

But that funding provision was removed in the amended bill that ultimately passed despite a veto by Gov. Paul LePage.

STATE’S STRATEGY

The Maine CDC will now decide where to send funding for certified needle exchange programs when it becomes available, according to Martins, the agency’s spokesman.

Martins pointed to other measures the state has taken to prevent the spread of infectious diseases from intravenous drug use. It supports HIV and hepatitis C testing programs, distributes hepatitis vaccines, works with other agencies to assist those with infections and has started a telemedicine program that trains primary care providers in rural, low-resource parts of the state.

The CDC epidemiologist did not consider any of those services when he ranked the vulnerability of counties across the nation, Martins pointed out, and the state of Indiana had not made any similar efforts prior to its outbreak of HIV. Unlike in Maine, there are 11 states that do not require reporting of hepatitis C, Martins said, and the state investigates every case of both diseases.

The state also has an emergency preparedness plan with a section on disease management.

“While we cannot predict when an outbreak will occur, the availability of testing, prevention efforts, a strong infrastructure and the many efforts listed above are among the factors that lessen the risk and make an outbreak unlikely,” Martins said.

While Miller applauded the passage of L.D. 1552, he expressed concern that funding was removed from the bill, as it means Maine CDC may now have to divert funding from other valuable prevention resources.

He also pointed to a few more steps that would help Maine’s injection drug users, particularly those in undercovered parts of the state.

One of the more “cutting edge” approaches is supervised injection centers. One such center opened in Vancouver and has been shown to reduce the number of overdoses, hepatitis C diagnoses and other drug-related harms, said Miller, who would like to see one open in Maine in the next five years.

But the “single biggest thing we could do for this population,” Miller went on, would be accepting federal funds to expand the number of Mainers who can receive Medicaid, aka MaineCare. That’s the health insurance program for poor Americans that got a boost under the Affordable Care Act, or Obamacare.

Gov. LePage has repeatedly vetoed lawmakers’ attempts to accept those federal funds, arguing there is no guarantee the funds would continue to flow.

What’s resulted is a “bottleneck” of drug-addicted Mainers who want to access treatment, but can’t afford it or the other medical services that would make them safer users in the short term, according to Miller.

“They’re stuck in this limbo, where they want to get better, they want to enter recovery, they want to start treatment,” he said. “But they don’t have access to the resources they need.”

Charles Eichacker — 621-5642

Twitter: @ceichacker

Send questions/comments to the editors.