Kim Vandermeulen’s company is trying to get creative.

Since the first of the year, Alternative Manufacturing in Winthrop has added between 10 and 15 employees, and the electronics manufacturer that makes printed circuit boards is looking for five or six more workers.

Production is up 40 percent over last year, and the need to hire is very high, Vandermeulen said recently.

“We’re looking for entry level, light manual labor up to machine operators. We’ll do a lot of training for machine operators, but our preference is for someone in those positions to have some training,” he said.

Alternative Manufacturing is not alone.

Across the region, help wanted signs dot the landscape. Businesses of all kinds are trying to fill positions, and they have been trying for months.

The reason behind the chronic need for workers is complicated, and it’s explained in part by the state’s unemployment rate.

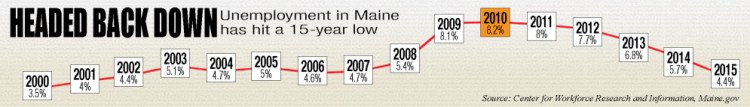

On Friday, the Maine Department of Labor in conjunction with the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, released the June unemployment numbers. At 3.7 percent, the state unemployment rate is up from May’s rate of 3.5 percent, but not by much.

“If you focus on that in a superficial way, it’s a great signal for economic condition,” David Findlay, an economics professor at Colby College, said.

On its face, he said, a low unemployment rate suggests a pretty healthy economic climate. “But at the same time, we’re dealing with an aging population and a labor force participation rate that’s dropping over time,” Findlay said. “I’m not sure we have as vibrant and dynamic an economy as policy makers and citizens would like. You have to look deeper.”

BROADER UNEMPLOYMENT RATE

The unemployment rate is one measure of the strength of an economy, and some argue it’s not the best one.

Glenn Mills, chief economist at the Center for Workforce Research at the Maine Department of Labor, said the labor force, whose activity is measured by the unemployment rate, is made up of people who have jobs and people who are unemployed but actively looking for work.

That leaves large groups of people unaccounted for, Mills said, including students, retired people and homemakers, for instance. People who have become frustrated and have stopped looking for work even though they may want a job are also not counted in the labor force.

The size of the labor force can be fairly fluid, thanks to changing circumstances. Mills said while students aren’t considered unemployed, they become unemployed as soon as they graduate and start looking for a job.

A broader measure of unemployment is the U-6 rate, which is a measure of all the unemployed, the people who want to work but have stopped looking and part-time workers who would like to work more hours.

In Maine, that’s calculated on monthly averages because the sample size is relatively small. From July 2015 to June 2016, the U-6 rate, sometimes referred to as the broader unemployment rate, is 9.3 percent.

That indicates that a larger pool of potential workers exists. But even so, companies are still having a hard time filling vacancies.

Joel Davis is in the same position as Vandermeulen. As managing director of Central Maine Meats in Gardiner, he’s trying to fill skilled positions at the fast-growing meat processing facility with mixed success.

“The more skilled workers we need — high-end butchers and meat cutters and middle management — they are harder and harder to find,” he said.

Entry-level workers are easier to find, he said, and those with a certain level of learning experience can be trained. Central Maine Meats has developed a training module with Kennebec Valley Community College that teaches the skills it requires in its employees, such as safe food handling and general math.

Once they’ve been hired, employees are on a path to build their skills and move up. “We march people along. And we pay more than minimum wage by a long shot,” Davis said.

But finding someone to work as a general manager overseeing operations has been a bigger challenge. “We’ve talked to many organizations, called headhunters, called half a dozen people looking for resumes and someone to fit that position. No go.”

RISING WAGES

Garvan Donegan is looking beyond the apparently low unemployment rate. Donegan is an economic development specialist with the Central Maine Growth Council in Waterville. The growth council is a public-private, collaborative, regional economic development agency.

“Just about every business I have talked to is hiring, looking to hire or worrying about (employee) retention,” Donegan said.

Workforce is the key challenge for any business the council is trying to recruit or retain. “We talk about tax incentives and TIFs and supply and demand economics,” he said, “but in the next year or so, we’re kind of at a critical stage in our demographics.”

Those demographics are the state’s aging population and shrinking pool of possible workers.

“Labor force participation is dropping,” Findlay said. “If fewer people are actively engaged in the labor market, it’s understandable why firms are having a hard time finding people.”

Donegan points to some bright spots that exist, including veterans and immigrants and naturalized citizens who can meet the demand for workers.

So can students. Early outreach, with pre-apprenticeship and apprenticeship programs, can connect students in area schools with businesses and allow them to test drive a career.

“We’ve been doing it most successfully with the mid-Maine Technical Center. We take some of the most thriving students and place them in a competitive interview process,” he said. That exposes them to the soft skills they need to develop to be successful employees, and they have a chance to see what working in fields as diverse as robotics, health care and construction is like.

“The student has the opportunity to review a career path, and the goal is to get them into a longterm position,” Donegan said.

But right now, he said, there is not a hospital or an information technology company that’s not looking for workers.

In fact, MaineGeneral Healthcare, with hospitals in both Augusta and Waterville, currently has several dozen openings for both certified nursing assistants and medical assistants, jobs that require basic certifications.

MaineGeneral spokeswoman Sarah Webster said 15 medical assistants are needed in physician practices in both Waterville and Augusta. About 30 certified nursing assistants are needed in Augusta. MaineGeneral has been working with Maine CareerCenters and the state Department of Labor to reach the unemployed and the underemployed to provide on-site training for both CNAs and medical assistants.

MaineGeneral is also making a move that often accompanies a tight labor market. It recently raised starting pay for new CNAs from $10.50 to $12 an hour.

Findlay said there’s no significant evidence that wages are rising on the national level due to competition for workers. But Mills said in Maine, wages started rising in 2014 and the trend has continued in 2015 and so far in 2016. He characterized the increase as “pretty healthy.”

Just as rising wages are one indication of a tight labor market, working more hours is another.

Vandermeulen, president of Electronic Services Corp., the parent company of Winthrop’s Alternative Manufacturing, said his employees are scheduled to work four 10-hour days a week. To meet demand, employees have volunteered to work a fifth day every Friday for a year, and many have worked every Saturday since mid-May.

In looking for workers, Vandermeulen said his company has been with Maine CareerCenters for some pre-job training and has been hiring high school students for positions that don’t require experience in electronics or manufacturing.

“For our company, our need to add workers will be pretty consistent,” he said. “We can see out a ways because our customers need to order pretty far ahead. For six months to a year it’s going to stay consistently high. It’s going to be tight for a long time. It’s an indication that the economy is doing better, so it’s not all bad news, but it makes it harder to hire.”

Jessica Lowell — 621-5632

Twitter: @JLowellKJ

Send questions/comments to the editors.