NORTH MIAMI, Fla. — It may be hard to remember now, but there was a time when a mysterious autoimmune disease baffled doctors and frightened a world unfamiliar with what is now called AIDS. Arthur Fournier recalls the rise of the epidemic far better than most. In some ways it made him. In others, it nearly broke him. Above all, it helped define the rest of his life.

In 1979, Fournier was a young doctor at Miami’s public hospital when patients exhibiting the symptoms of AIDS began flooding in — only these patients weren’t gay men, who accounted for many early cases of the disease. Rather, they were Haitian.

Confounded, Fournier and some of his colleagues soon published a study about what they were seeing among their Haitian patients, concluding “it is possible that this syndrome … is the same as that found among homosexual men.”

Their work would go a long way toward helping the medical community better understand how AIDS spread, but it also had unintended consequences: Just being Haitian was initially listed by the federal government as a risk factor for AIDS, along with heroin use, hemophilia and homosexuality — a macabre “4-H club,” as it became known.

For years, discrimination and recrimination against Haitians ensued. Fournier and the other doctors were blasted for committing bad science, asking biased questions, failing to employ Haitian Creole translators when talking with their patients and targeting an immigrant community derided as “boat people.”

Now, some 35 years later, Fournier is one of the Haitian community’s biggest champions: A man whose early missteps led to a career dedicated to improving access to medical care for Haitians in Miami and back home.

“I think I believe in reincarnation, and I’m convinced he was Haitian in a different life, because he has given and done so much for Haiti and the Haitian community,” says Dr. Marie-Denise Gervais, a professor of medicine at the University of Miami who works with Fournier in a network of school-based health clinics.

Gervais, a native of Haiti, remembers feeling the stigma about Haitians and AIDS as she pursued her medical degree. For a time, even after a ban on Haitians donating blood in the U.S. was lifted, she stopped giving blood just to avoid being questioned about her heritage.

Gervais sees Fournier as a pioneer of the movement to improve health care for Haitians, not as the cause of the stigma.

“Looking back, obviously he wrote some article, but the scientific community had no clue. They’re seeing all these cases, and this is how the scientific mind works: You’re trying to put all the pieces of the puzzle together. When you’re right, it’s wonderful, but sometimes you have trial and error before you get it right,” she says.

From Fournier, now 65, there was never an “I’m sorry” for what happened in the aftermath of those early AIDS studies. Shortly before the research in Miami was published, officials at the Centers for Disease Control began warning doctors who cared for Haitians that their patients might be prone to terrifying infections.

In the panic that followed, Haitians in the U.S. reported losing jobs, and their children were taunted at school. The U.S. government would briefly ban Haitians from donating blood. Anger in the Haitian-American community manifested in massive rallies that blocked the Brooklyn Bridge and Miami streets.

Fournier, who endured pressure to cut back on his AIDS work, says he never felt like he had to apologize for contributing to the stereotype that shadowed Haitians for years. Rather, he says: “I did it with my words and actions.”

Growing up north of Boston, Fournier was the oldest of six children whose assembly-line worker father died at age 40. In medical school, he was keenly aware that he hadn’t shared many of the privileges enjoyed by most of his classmates — they were the sons of lawyers and doctors, while he was selling his own blood to help pay for the engagement ring he gave to the woman he courted with dates in the medical school cafeteria.

He wanted to work with the poor — circumstances he found familiar — and after completing his residency at the University of Miami hospital, he spent two years practicing medicine in rural Virginia. Fournier’s return to Miami to teach public health in 1978 coincided with the arrivals of thousands of Haitians, mostly by boat.

When these Haitians got sick, they lacked the money to go anywhere else but Miami’s public hospital, exposing Fournier for the first time to Haitian culture and AIDS.

“The people in the hospital, they were going nuts,” is how Fournier remembers those early days of the AIDS epidemic. He would step into elevators at Jackson Memorial Hospital to see orderlies dressed head to toe in protective suits just to transport AIDS patients, whom some residents refused to examine. When he got home from work his wife, terrified of infection, ordered him to shower before he did anything else.

Amid the criticism from Haitian community leaders that the doctors had failed in the most basic aspects of medical exams — simply asking their patients about their health — Fournier stood by his work and continued to treat Haitians and other patients with AIDS.

“I feel like they were my brothers and sisters,” says Fournier, who later published research about the socio-economic forces that helped HIV and AIDS spread worldwide. “It’s not really guilt, but I was extremely disappointed when … our identification of HIV amongst the Haitians so led to their stigmatization. That was so wrong.”

Fournier and others in the medical community later would come to understand that poverty played a significant role in AIDS cases among Haitians, the homeless and other impoverished communities.

Prostitution and sexual tourism, drug use and social and political forces affecting women, families and minorities also facilitated the spread of AIDS. The most effective treatments and education about preventative measures such as condoms required large amounts of money and time from a limited number of doctors — resources often out of reach for the poor.

In the years that followed, Fournier focused on community health and finding new ways to provide health care for the homeless, immigrants and schoolchildren in South Florida, projects funded with more than $71 million in grants he secured. He served for 25 years as associate dean for community health at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine.

In Miami’s Little Haiti, he participated in health fairs and helped fund a medical clinic at the Center for Haitian Studies. He developed a program to provide comprehensive health care to schoolchildren in Miami-Dade County’s impoverished, largely immigrant neighborhoods. Today, 11,000 students receive care that includes vision, dental and mental health services at clinics based in 10 area schools.

Fournier also invented a device that allows women to privately screen themselves for sexually transmitted infections, something that researchers who tested the device among Haitian women in Miami noted was valuable in a community still stung from the AIDS stigma and reluctant to divulge personal information to doctors.

The doctor worked to redeem his early mistakes with Haitians by becoming fluent in Haitian culture and Creole, the country’s most widely spoken language, says Marleine Bastien, a longtime Haitian-American advocate who has worked on health care issues in Little Haiti with Fournier since the 1980s.

“It lessens the impact of his involvement, the fact that he was able to leverage it with such good work over the years, always trying to understand the people … and making them feel important enough to invest his time, to learn the language and bring information about prevention and access to health care to them,” Bastien says.

Soon, the culture Fournier found charming but mystifying when his first Haitian AIDS patient showed up in 1979 became like a second skin.

In 1994, Fournier co-founded Project Medishare, a nonprofit that provides health care in rural Haiti, far from the from the resources centralized in the country’s teeming capital. It was then that he made his first trip to one of the world’s most impoverished nations.

Like most first-time visitors, Fournier was shocked by the extreme poverty he saw. When his vehicle stopped in a slum in the Haitian capital, little girls rushed to his window, their hands reaching for the disposable cups they spotted inside. Fournier watched them take the used cups and dip them into puddles for something to drink.

Something clicked: The girls’ poverty and lack of resources left them susceptible to illness, not their nationality. Fournier thought back to the Haitian AIDS patients he had seen in Miami.

In the 20 years since that first visit, Fournier has been back more than 150 times, bringing University of Miami medical students to teach them about Haitian culture in hopes of encouraging them to pursue careers in global health and change medicine for the poor, says Dr. Barth Green, who co-founded Medishare with Fournier.

“He’s a very special person who does believe in Santa Claus and the Tooth Fairy,” says Green.

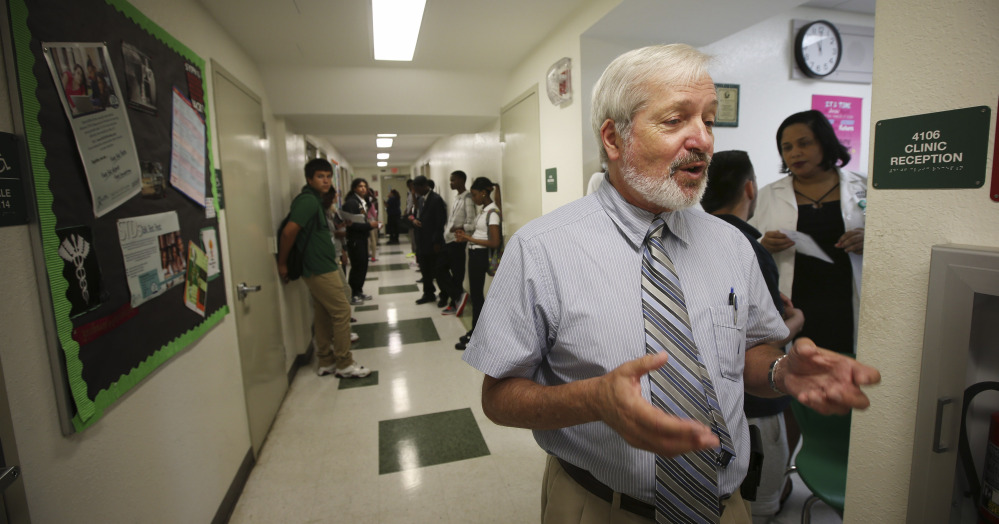

Today, Fournier still travels to both Haiti and parts of Miami, continuing his work with the community to which he committed his career. He recently showed off the benefits of a medical clinic embedded in a North Miami high school, and he reflected back on his years of work with the Haitian people.

“When you come from impoverished circumstances, I think you realize there are barriers to class and culture that consciously or unconsciously interfere with the people you’re trying to serve,” Fournier says. “I used to think that all you had to know to be a good doctor was to know medicine, but you really have to have a bond with the people you’re trying to serve.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.