After weeks of using only bottled water for drinking and cooking, two schools in Fairfield-based School Administrative District 49 are allowing students to use tap water there again.

Benton and Clinton Elementary schools initially put water out of service after tests revealed dangerously high lead and copper levels above the federal limits at which a school has to take action. After replacing water fixtures throughout the schools and conducting multiple rounds of testing, the principals say the water in the schools is now safe to drink again.

Benton Elementary put water back in service on Dec. 9 and Clinton Elementary did the same around Dec. 6.

Action must be taken when more than 10 percent of samples show a water supply’s lead level is above 15 parts per billion for residential areas and 20 ppb for schools, or when a water supply’s copper level is above 1.3 parts per million, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

Lead is most dangerous to children, as it can cause developmental and behavioral delays, and high levels of copper can cause harmful symptoms such as nausea and irritation, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The original tests at Benton Elementary, conducted by the Kennebec Water District in October, were taken at three locations throughout the school and showed levels of lead at 670 ppb, 78 ppb and 57 ppb.

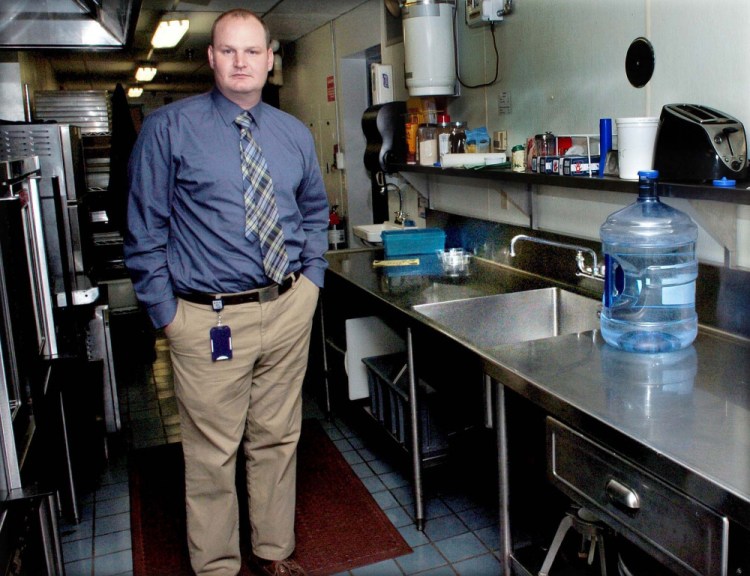

The school has since replaced all water fixtures in the building, according to Principal Brian Wedge, and the water district replaced the water meter with an updated, lead-free version. Teachers are also regularly running the faucets in classrooms for a few minutes on Mondays in an effort to “flush” the water, Wedge said. Flushing gets the water that has sat in the old pipes overnight out of the system, so the water people do get will come directly from the water utility’s system.

After all fixtures were changed, the school hired Waterville engineering firm A.E. Hodsdon to take additional samples. All results were below the federal action level.

The samples, taken on Dec. 1, showed lead levels ranging from 1.29 parts per billion to 13.9 ppb at four testing sites. The highest level was found in the water at the boiler room spigot, which once had the highest lead level — 670 ppb.

The firm also found that the water samples had copper levels below 0.5 parts per million.

After the district received the unexpected results from Benton, it had tests done at all its other schools.

A.E. Hodsdon found that Clinton Elementary School also had levels of lead and copper above the federal limit for schools at some areas in the building.

The results from Nov. 14 showed one site with a lead level of 150 parts per billion and another site with a copper level of 1.5 parts per million.

After replacing all the faucets and fountains throughout the school, samples from the school’s water showed all levels to be within federal limits. The town also paid to replace a water meter at the entrance to the school.

Lead levels in the water samples ranged from 2.64 ppb to 10.2 ppb, and copper levels ranged from 0.12 ppm to 0.82 ppm.

The drinking fountains at Clinton had been out of service for longer than the minimum eight hours required when sampling for lead or copper levels, which means the results could be considered “worst-case samples,” said Ricky Pershken, a geologist with the firm, in a letter to SAD 49 administration.

“Once these fountains are placed in service, we expect the lead and copper levels to decrease,” he said.

No samples taken at other schools in the district revealed lead or copper levels above the federal action levels.

The school is still waiting for two new fixtures, district superintendent Dean Baker said, and still is providing bottled water in those areas. Otherwise, water was put back in service around Tuesday, Baker said.

Baker said the district is planning to do annual testing at all schools.

Three Maine drinking water associations have since partnered with the state’s Drinking Water Program in an effort to provide financial and technical support to schools and water utilities for voluntary lead testing. The program will pay for public water utilities to conduct up to 10 tests at each school that they service.

As of now, neither the state nor the federal government requires schools to test their water if they’re serviced by a public water utility. While water utilities have to test their supplies, lead leaching often occurs after the water enters an individual building’s system, which may have older pipes that contain lead soldering.

Madeline St. Amour — 861-9239

mstamour@centralmaine.com

Twitter: @madelinestamour

Send questions/comments to the editors.